Rebecca More’s inspiring journey from stroke to helping others to speak

When highly-credentialed nurse Rebecca More left hospital after suffering a stroke at the age of 47, she was unable to express concepts a simple as ‘rain’ and ‘sky’. Now she is working wonders in her new role.

Bundaberg

Don't miss out on the headlines from Bundaberg. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Nurse practictioner Rebecca More may be one of the most highly qualified staff members at Childers’ Forest View aged care home in more ways than one.

Beyond her storied medical career, Rebecca experienced a debilitating stroke at the age of just 47, an experience which is now helping her to deliver superior care to Forest View’s residents who are going through a similarly harrowing and bewildering recovery from one of Australia’s most lethal conditions.

MORE NEWS: Why state watchdog flagged problems with Bundaberg council

After a stint as director of nursing at Queensland’s Central West hospital and health service, in 2022 Rebecca was working as a remote area nurse in the Northern Territory.

On November 29, 2022, Rebecca returned home from a day’s work in the Central Australia health service offices in Alice Springs.

At about 7pm, she was texting her son, Austin, who had sent her a photo of his new baby.

When she went to reply, Rebecca found that she was unable to formulate a response using the phone keypad.

“I couldn’t reply ... I had no pain, but it was like there was a leaning part in my brain with a shadow over it,” she said.

After sending a garbled reply, Rebecca said she “went blank”, which drew the concern of her husband, Grant, himself a second year nursing student.

Grant stood in front of Rebecca and asked “what did Austin say?”, repeating the question when Rebecca didn’t respond.

“In my head, I was looking for a word or looking for some type of communication to say to him what the conversation was about; but it was gone, I was silent,” Rebecca said.

Already suspecting Rebecca was experiencing a stroke, Grant went through the FAST protocol for confirming the signs of a stroke - checking her face and mouth had drooped, whether she was unable to lift both arms and whether her speech was slurred or confused.

With Rebecca ticking off all the boxes, Grant rushed her to Alice Springs Hospital, knowing a timely and urgent response was the fourth and final criteria that needed to be satisfied.

Rebecca had no recollection of the trip to hospital, but was aware she was taken for a CT scan which showed no troubling signs, leading to doctors making an initial diagnosis of a migraine.

The next day, Rebecca went back for more tests and an MRI which showed that a hole in her heart had led to four blood clots developing in the left side of her brain, blocking the blood supply to the part of the brain responsible for comprehension and production of language and causing the language disorder of aphasia.

While stroke is often thought of as an older person’s disease, National Health and Medical Research Council studies have shown more than 30 per cent of stroke survivors are under 65.

With the debilitating effects including loss of speech, vision and other cognitive abilities, the burden of stroke is felt most acutely among younger patients for whom long-term life plans including a career are thrown into disarray.

After being discharged from hospital, with doctors telling her she may not be able to return to nursing, Rebecca went home with her entire framework of worldly concepts wiped clean.

“I went out into a world I did not know,” she said.

“I did not know where I was, what country I was in; it was completely gone.”

With Grant’s unwavering assistance, Rebecca began the long road of re-learning words in a child-like state of wonder.

On the fifth day, she was outside playing with her dog when it started to rain, a phenomenon for which Rebecca at this stage had no conception.

“I said ‘water’, and then I would point to the sky because I didn’t know it was called ‘sky’,” Rebecca remembered.

“And then I would point to my arm because I didn’t know it was called ‘arm’; Grant said ‘that’s the sky, this is your arm, and this is rain.

“And it was the first moment that I felt rain, and I don’t recall rain prior to that moment.”

Unsure of their next steps, Grant and Rebecca returned to Townsville where they owned a house, but an initial round of medical appointments left them frustrated when a doctor relied too heavily on prescribing antidepressants.

“Eventually Grant just ripped up the script and said ‘she’s not depressed, she just wants help’,” Rebecca said.

Rebecca’s rehabilitation only began three months after her stroke, when she and Grant fortuitously learnt a former colleague, Dr Bryce Nichols, was living in Townsville.

Dr Nichols organised the cardiology appointments to repair the hole in her heart, and the neurology, speech therapist and physiotherapy appointments that she needed.

“Really, he kind of became a bit of a bit of a saviour for us,” Rebecca said.

Now a GP working at the Urgent Care Clinic and Friendlies Hospital in Bundaberg, Dr Nichols said it was the lack of coordination with community based providers that let Rebecca down.

“Stroke is one of those conditions where the most important factor is rehabilitation,” he said.

“And moving from the treatment phase to the recovery phase is often where patients can feel like they have the least control.

“In Rebecca’s case, it was an example of not having that coordination in the community setting early on.”

Bryce said Rebecca’s rehabilitation journey was “remarkable”, primarily due to the awakening of artistic talents in Rebecca of which she had shown no signs prior to the stroke.

“Stroke has this tendency to take so much away,” Bryce said.

“But I think Bec’s a great example of where it’s unmasked abilities she’s never know she had before.”

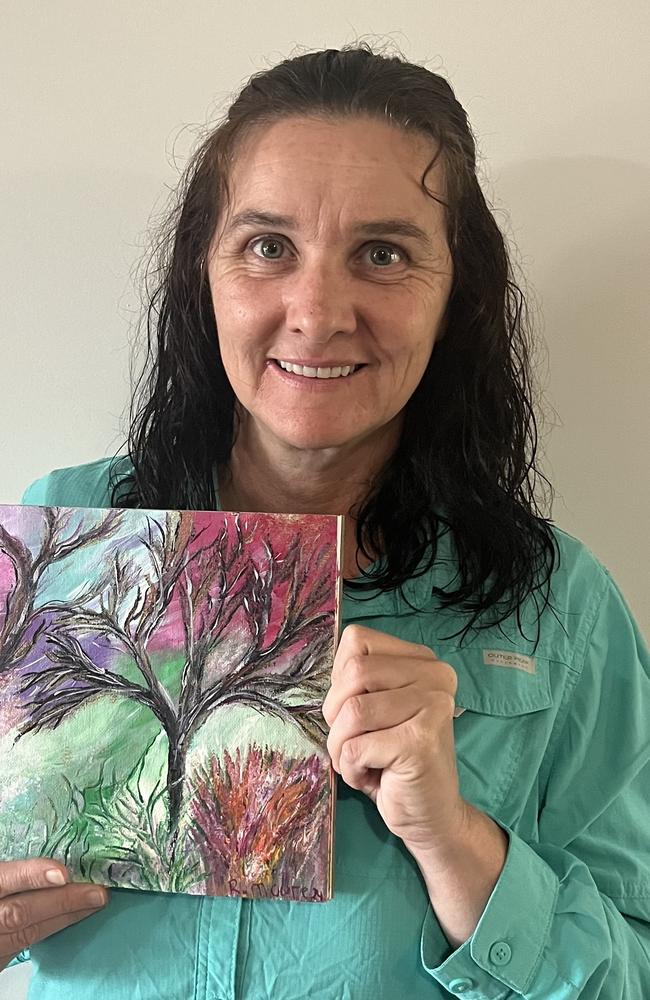

In the course of her rehabilitation, Rebecca was drawn to create artworks documenting the stages of her recovery, with the neural paths of the brain represented through sinuous tree branches.

The first, created in the first few weeks after her stroke, includes a red orb representing the part of her brain that the stroke took away, with another work showing her brain creating new pathways.

A later, more vibrant work, was created 10 months after her stroke, on the day the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency gave Rebecca clearance to resume her nursing career.

“It was my day of independence,” Rebecca said.

“This is how my brain tree felt on my first day of going back to nursing, just full of colour and a world of opportunity.”

After regaining her registration, Rebecca called a former colleague from her remote nursing days, Julie Mayor, CEO of the Forest View Childers aged care home.

Since moving to Childers in February and starting at Forest View, Rebecca said she is gradually building back her familiarity with the career that made up such a significant part of her life before the stroke.

“It’s been great ... I’m starting to feel it’s not as foreign anymore, so I’m starting to feel like a nurse again,” Rebecca said.

Julie said Rebecca’s experience as a stroke survivor, including her use of art to further her rehabilitation, made her an invaluable contributor to Forest View’s innovative approach to stimulating residents’ creativity through activities oriented around art and music.

Rebecca’s clinical knowledge was intact, with her only challenges being around recalling the correct terminology at times.

“Her achievements are absolutely phenomenal,” Julie said.

“She’s probably the highest nurse practitioner, potentially, in the country.

“She can run rings around me with her knowledge about everything, but she just has trouble sometimes to find the right word.

“Clinically she’s still outstanding.”

Due to her close familiarity with the inner experience of aphasia, Rebecca has already worked wonders in coaxing language from some residents who had not spoken for as long as they had been at Forest View.

“Because she’s gone through the experience of people believing that she didn’t know anything, because she couldn’t speak, she’s able to then resonate with older people who have that same experience with stroke, dementia, or anything else,” Julie said.

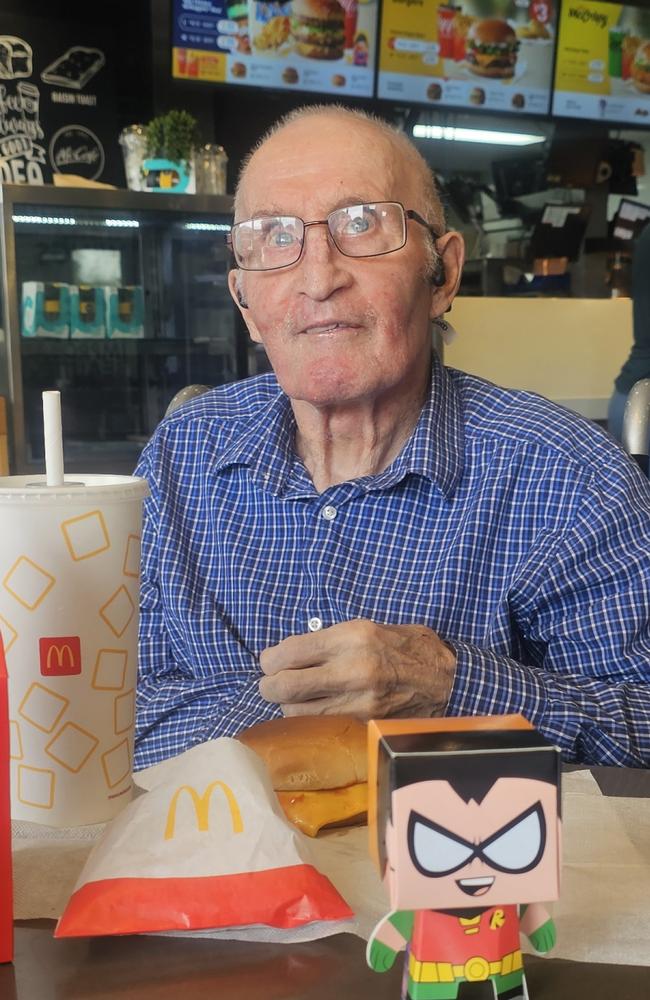

One resident, a man in his eighties named Keith, had not spoken for four years until Rebecca worked with him for just one hour.

“He got to a stage where he looked at her and said ‘you’re wonderful’,” Julie said.

MORE NEWS: Govt says intersection where three died in fireball horror ‘safe’

Rebecca said her approach involved “finding a light” for residents to make their way out of a tangle of frustration and confusion when they were attempting to speak.

“You want to be able to communicate, but it’s like being in a prison in your brain,” she said.

“So when I’m speaking with residents that have had stroke, I remind them that we need to find a light for them to get out of that particular area where they’re feeling frustrated.”