Bodies of two men found in saddlebags in hunt for Queensland’s last bushrangers

THE horse was drenched in blood. Human blood. The men had been out searching for days and this find signalled a sinister twist in the hunt. What they found in the saddlebags was even worse.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY were days into the hunt when they came across a horse, its saddlebags stuffed to the brim.

Now they had both horses. Of the Kenniff brothers and the men who’d gone to apprehend them, there’d been no sign.

There had been blood all over Albert Dahlke’s horse when they’d found it that first day. Blood on the saddle. Blood nearby. They’d found burnt patches of ground where efforts had been made to conceal the violence that had taken place there.

Now, days later, men and horses dropping from exhaustion as they searched the Queensland bush, they’d come across the animal Constable George Doyle had been riding.

Another saddle splashed with blood.

They opened the stuffed saddle bags to piles of charcoal. It took a moment to comprehend.

They’d found Doyle and Dahlke.

The hunt for Queensland’s last bushrangers, however, would not stop.

In 1891, when the two eldest Kenniff brothers crossed the New South Wales border into Queensland, they’d already earned a reputation for havoc.

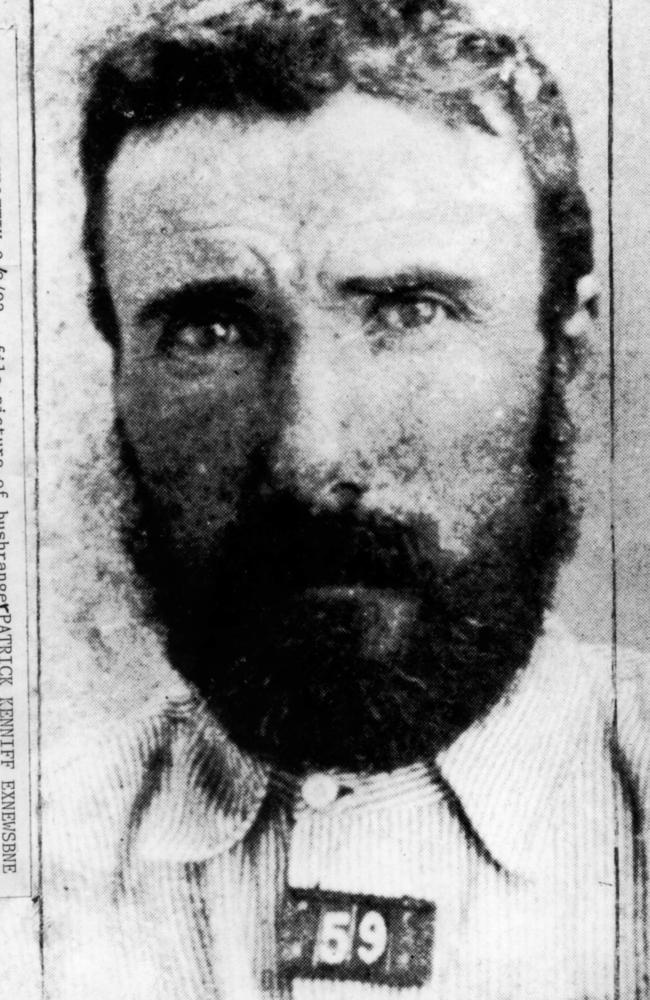

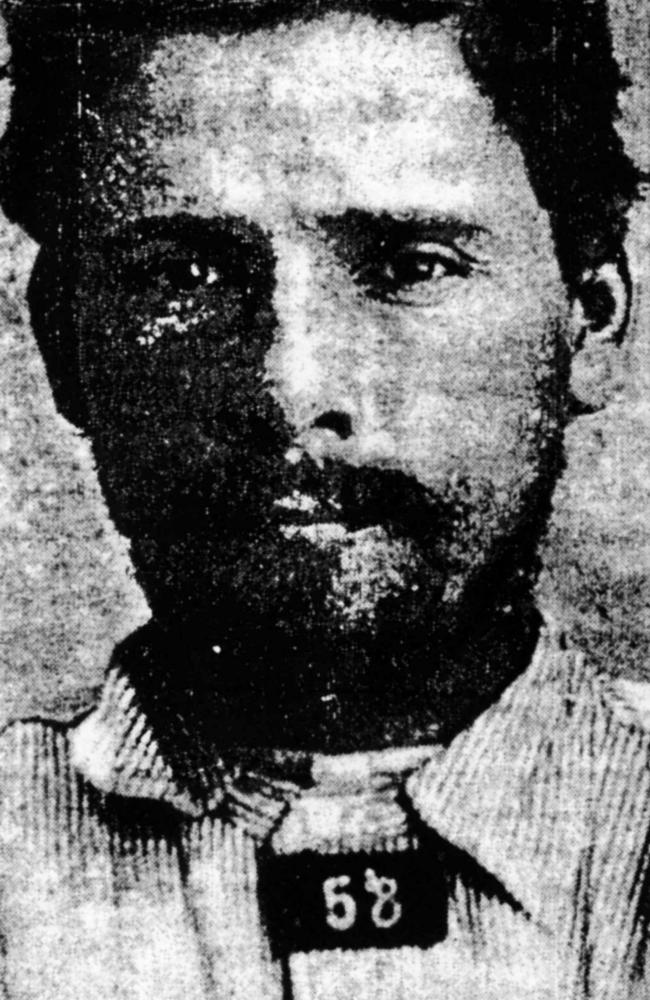

Patrick and his younger brother James both had convictions for cattle stealing, dating back to the 1880s when they were little more than children.

The brothers had been in the frame for stealing horses in Lansdowne. The animals were found with the brands burned from their flesh and the numerals on their necks cut out with a pen knife. But that was one they’d get away with.

They were at it again after landing in Queensland, and in 1895, a judge sent them both to prison for livestock theft.

After one stint in prison, the brothers made their way to Upper Warrego, in Queensland’s south west, where they took up a grazing lease on a property known as Ralph Block.

They amassed a herd of 1000 cattle and were soon terrorising neighbours whose own animals were disappearing at a steady rate.

The Kenniffs’ run was on Carnavorn Station. Sometime around 1900, the station was handed over to new owners. It was in chaos. Cattle thieves roamed the land.

A new manager, a young man by the name of Albert Dahlke, was sent in to clean things up.

“It was known that he was the man of all others to take no half measures with cattle stealers,” a newspaper reported.

“A fine young fellow, active and fearless, a splendid bushman able to ride any horse that had ever been saddled, full of energy and determined to root out the gangs of cattle stealers who had made a profitable living during the (former owner’s) regime.”

The Kenniffs had not held onto their land.

Terrified neighbours had reported missing stock and complained of the brothers roaming the district, armed with guns.

The Kenniffs were told their lease would not be renewed. To ward off the wayward family and other gangs, police moved into Ralph Block and built a permanent station on the land.

But it was Dahlke who would come to blows with the family.

He came across James, the younger of the Kenniff boys, on the run one day and told him to clear off. “Look here,” Dahlke told the bushranger. “If I ever catch you on Carnarvon again, I’ll thrash you.”

But it wasn’t long before he caught James on the station again, claiming to be looking for a lost horse. “Blows followed,” a newspaper reported, “and (James) received a severe thrashing at the hands of the young station manager”.

The Kenniff brothers soon returned, looking to square things with Dahlke. But Dahlke was out on a run, so they took their anger out on a stockman named Ryan, violently assaulting him.

Now the police were involved. Constable Doyle had a warrant for Patrick – charges of horse stealing and robbery. He rode out to find the Kenniffs, accompanied by the ever fearless Dahlke.

They took with them an Aboriginal tracker by the name of Sam Johnson, a “finely built, athletic” man well known and respected in the area.

The group of three carried one firearm between them – Constable Doyle’s police-issue revolver.

On Easter Saturday the team was ready to move into the Kenniff camp where the brothers’ lived with the rest of their family.

They spotted them as they came over a ridge. Patrick, James and a younger brother, Thomas.

The men gave chase, pursuing the brothers as they scattered in different directions.

Dahlke, a talented rider on an expensive bay mare, set his horse after James, who’d taken off towards a creek.

He was on him in moments, leaning from his horse to grab hold of James’ bridle.

Constable Doyle was close behind, grabbing James by the collar. The policeman got off his horse and pulled the bushranger to the ground.

Johnson, the tracker, had taken off after the other two brothers. But when he found himself alone, he turned his horse and rode back to join the others.

Doyle and Dahlke, holding James down, shouted for Johnson to get the handcuffs from the packhorse.

He turned his horse again and, moments later, heard the reports of a gun. Five shots rang out through the bush. The weapon was not Constable Doyle’s, Johnson thought. The blasts packed far more power than a police issue revolver.

The unarmed tracker was trying to decide what to do when two horses burst through the bush, charging in his direction.

It was two of the Kenniff brothers.

Johnson fled into the hills, riding until he found help.

The hunt for the Kenniff bushrangers was one of the greatest in Queensland history.

It was rough country. Police and locals searched caves and valleys. They trekked through thick scrub, riding horses until they dropped.

Johnson took police back to the spot where he’d left Doyle and Dahlke. They uncovered bullet-damaged logs, patches of blood and evidence of fires that had been lit in an attempt to destroy the evidence.

Dahlke’s horse was found almost immediately, its saddle empty and splattered with blood.

Doyle’s horse they found two days later, the saddle bags holding the grisly and charred remains of the missing men.

More searchers arrived each day from Brisbane. Horses were found for the many police officers sent to the district and they took off into the bush.

A reward of one thousand pounds was offered for the capture of the brothers, but despite the enormous number of people now involved in the hunt, the Kenniffs remained on the run.

It would be three months before police tracked the brothers to a camp six miles from Mitchell.

The officers approached with bare feet, noting a trio of horses left at the ready for a hasty escape.

The officers opened fire on the horses, taking two down, as the Kenniffs scattered.

An officer fired at James, who fell as he fled into the bush. He was arrested unharmed.

They led James in cuffs through the scrub in the same direction his brother had fled.

Half an hour later, they found Patrick.

He’d been waiting for them, two rifles at the ready.

There were 50 policemen and 16 Aboriginal trackers in the area searching for the fugitives. More in nearby towns.

The officers holding James kept their distance, and a shouted negotiation took place.

Eventually, Patrick surrendered.

“The police obtained a clue to the whereabouts of the two brothers yesterday,” a newspaper reported.

“A farmer, about five miles from Mitchell, reported to the police that a bag of wheat had been stolen from his place the preceding night.

“Investigations resulted in the police following the tracks of two unshod horses from a shed at the farm into a small patch of scrub, where the bag had been placed on the ground and the horses allowed to feed out of it.

“The tracks of two men were also observed but darkness setting in, the party returned to Mitchell for the night.”

The two brothers were brought to trial and Johnson became an important witness.

After days of sensational evidence, a jury found the pair guilty of murder.

Patrick would face the gallows. James’ sentence was reduced to life imprisonment, the court ruling Patrick would have fired the shots that killed Dahlke and Doyle.

The elder of the Kenniffs met his end at the infamous Boggo Road jail on January 12, 1903.

His death was witnessed by a huge crowd of police, officials and newspapermen.

“Have you anything to say before you die?” the chief warder asked the condemned man.

Patrick’s voice was loud and firm.

“I have told you before twice, I am an innocent man,” he said.

“I thank all the warders for their kindness towards me and my well-wishing friends.

“I say goodbye, and God have mercy on my soul.”

###