Anti-violence campaigner Jonty Bush wants to meet her sister’s killer ahead of his release from jail

SHE helps victims of homicide heal but Jonty Bush is still on that path after the deaths of her sister and father. Now she wants to face the man who stabbed her sister 41 times.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE need for vengeance has gone. No longer are nights spent musing about ways to kill him. Oh,the thoughts she had! Now, when morning comes, Jonty Bush is not hit by a white-hot rage but the soft, sweet breath of her three-year-old daughter, Albie, snuggling in as they watch the sunrise.

The need to know how he occupies his days has gone, too. And how he feels is of passing interest. But how he looks, that’s important. Because 16 years after Kris Slade took a knife to her 19-year-old sister Jacinta Bush and murdered her, he is eligible for release.

“I want to lay eyes on him,” says Bush. “I want a visual. I want to see how he moves and looks and talks. That won’t be achieved through a photo, which I’ve been offered.”

It’s an unusual request. The Justice Department told Bush she was the first person to seek a pre-release meeting with the person who killed their loved one. But Bush often takes the unconventional path. In the years after two family tragedies within four months up-ended her world at the age of 21, she has been recasting the role of victim, determined to live a big, happy life rather than let hate destroy her, too.

“I get up early, make the most of every day,” says Bush. “I always keep in front of my mind that I want to experience what I can while I can because you don’t know what’s around the corner. I owe it to myself and everyone around me to do and see and live and experience everything that I can in this life.”

It wasn’t easy to get to this point. It took years before she could “unplug” from thinking about Slade. “Is he dreaming about Jacinta, is he upset, does he think about us, does he think about (Jacinta’s daughter) Lydia and what he’s done?” says Bush. “That was intense for years.”

If she wasn’t thinking about Slade, she was thinking about Travis Paterson, the man who had been a pallbearer at Jacinta’s funeral. He’d been a family friend, the brother of Luke, Jacinta’s estranged boyfriend at the time of her murder and the father of their daughter, Lydia.

It was Travis Paterson who struck Bush’s father, Robert, during an altercation over access to Lydia, then 20 months. Robert collapsed and later died. Paterson stood trial for manslaughter and assault occasioning bodily harm but was acquitted in 2003, sending Bush into another spiral of hate and vengeful thinking.

“I was gutted,” says Bush, who turns 37 today. “I was super angry. I was angry at Travis, I was angry at the system, I was angry at police, I was angry at the family courts and when he was acquitted … it made me question everything from friendships, to whether I should be law-abiding any more. If people can just take, why not just take? All that stuff.”

But by then, Bush had become parent to her brother, Jason, then 13.

“I think having Jase was the best thing ... if I didn’t have Jase things would have been very different.” And she wanted to keep Lydia in her life. “I realised if I wanted to have genuine and meaningful contact with her, I couldn’t be holding this grudge,” says Bush. “She’d pick up on that and it would be uncomfortable for her.

“And I deserved better too,” says the woman who would become Young Australian of the Year 2009 for her advocacy for victims of crime. “If we keep reliving things, they will continue to affect us. Yes, it was unjust and unfair and he was wrong. But at some point you go, ‘But now what?’ ”

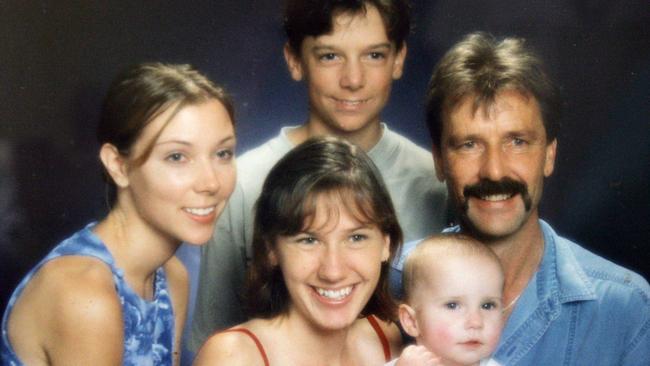

To appreciate how far Bush has come, how exquisite life is for her now, we need to go back to before double tragedies put her grief on public view. There they were, Bush, Robert, Jacinta, Jason and an angry orange cat, bouncing along the highway in a borrowed pie truck, their few possessions wedged around them. They were broke. Bush’s mother, Marlene, had left them. They were bound for Vinnies to buy some beds before moving into a rental house. And it was the best the then 17-year-old Bush had felt for years. “I had this real sense that this is where life would begin,” says Bush now, sitting in the loungeroom of her Brisbane home.

She smiles at the memory, the optimism of youth. It would all be up, up, up from here, she told herself on that 130km trip from Kilkivan, west of Gympie, to Maroochydore on the Sunshine Coast. Gone would be the drinking, the truancy, her mother’s unpredictability, her father’s battles over a gold mine gone wrong. She’d been given another chance, scraping into the human resources course at the newly opened University of the Sunshine Coast and she wasn’t going to mess it up.

One day, she’d wear a business suit. To Bush, that was the pinnacle of success. “Women in suits just looked together. And I just wanted to be that.” There’s a moment of contemplation before she adds, “I feel I’ve lived a whole life trying to be anything other than Mum. Trying to be together.”

Marlene lives with schizophrenia, which is now being managed. As Bush was growing up, however, Marlene had little mental health support. Bush knows that now, but as a young girl, her mother’s moods and erratic behaviour were crippling. Once, Marlene was convinced the colour orange was evil. Everything in the house that was orange was dumped on the footpath. She would walk for hours, around the house or further afield, often forgetting about pots on the stove. “Things would be smouldering,” Bush recalls. “Or we’d be trying to sleep and she’d come in and whisper at us. Really did your head in.”

The distress was so acute that when they were in their tweens, Bush and Jacinta – “my little mate” – made a heartbreaking pact: if one of us is diagnosed with schizophrenia, the other will admit her to a mental hospital. Forever. That way, they figured, the girl could never marry and have children and the cycle would be broken. “Terrible stuff,” she says. “It’s terrible as a kid, all you want to do is fit in,” Bush says. “I remember that sense of embarrassment, disappointment, anger, about not having a normal mum and not feeling supported.” With a seething sense of shame and injustice inside her, Bush went off the rails. “I was really self-destructive and I certainly had those teenage years of experimenting with drugs and alcohol and sexuality and criminality, all of that,” she says. “Then we moved to Queensland and it probably got worse.”

Bush’s early years were spent just outside Hobart, Tasmania, in a housing commission area but in 1993, when Bush was 14, her mother’s desire to live somewhere warmer led the family to move to Kilkivan. Marlene had found a gold mine to invest in, the One Mile Mine, and Robert, a painter by trade, was to work it and be paid a wage. The Bushes mortgaged the Tasmania house and sank $100,000 into the mine.

Soon after arriving, they discovered it was unprofitable. Within months, Robert was on unemployment benefits, while still plugging away at the mine. “He was such a good man, had a strong work ethic and he just wanted to make it work,” Bush says. “He was there from sunrise to sunset.”

Arguments between the investors and the mine owner, Karl Brooks, grew louder and Marlene’s mental health grew worse. “It’s hard to go to school and pretend everything is fine when you’ve got Crazy Town going on in the background.” So, she didn’t go very often. She’d wag school, drink, take risks. In Year 12, Bush went to a party on a farm outside Kilkivan. When she woke, alone, she knew something was wrong. As days wore on, it became clear that “a number of men had had sex with me when I was unconscious”. She reported it to police, who told her it would be hard to prosecute, and she dropped the complaint.

It’s the first time Bush has spoken publicly about the rape and when I use that word a few moments later, she flinches. “It’s funny, it was only a few years ago that I was even able to support that,” she says. “I know it, cognitively, but I’ve still got that thing of rape being a woman clubbed and dragged off the streets. These were friends. Or who I thought were friends. It was awful, I felt really … I won’t say suicidal, but shocked.”

A circuit-breaker came in the guise of a guidance counsellor a few weeks later. On one of her rare days at school, the counsellor gave her a talking-to, telling her how limited her job options were looking. “That was a big wake-up call. I wanted to get out of this town. I remember that real moment of, ‘there is no white knight coming’. If I don’t step up, I’ve got no one to blame but me.”

So she changed. She went to her teachers, apologised for not turning up and begged for a second chance. Catch-up exams were set and she buckled down, even after her mum had left home. “We came home from school and the house was stripped,” she says. “Mum had got a truck in and cleaned us out apart from our beds and uniforms, some clothes.”

Meanwhile, the family’s hopes of striking it rich were dead. Brooks was convicted of charges relating to the mining venture, and was jailed. Robert never recouped his money. But he got a pie truck from a friend, loaded up his kids and cat, headed for Maroochydore and started again. “And I put on my suit and got into business mode and I totally changed,” says Bush. “After getting to the Coast, I never talked until many years later about anything from my past. It was a life that didn’t happen.”

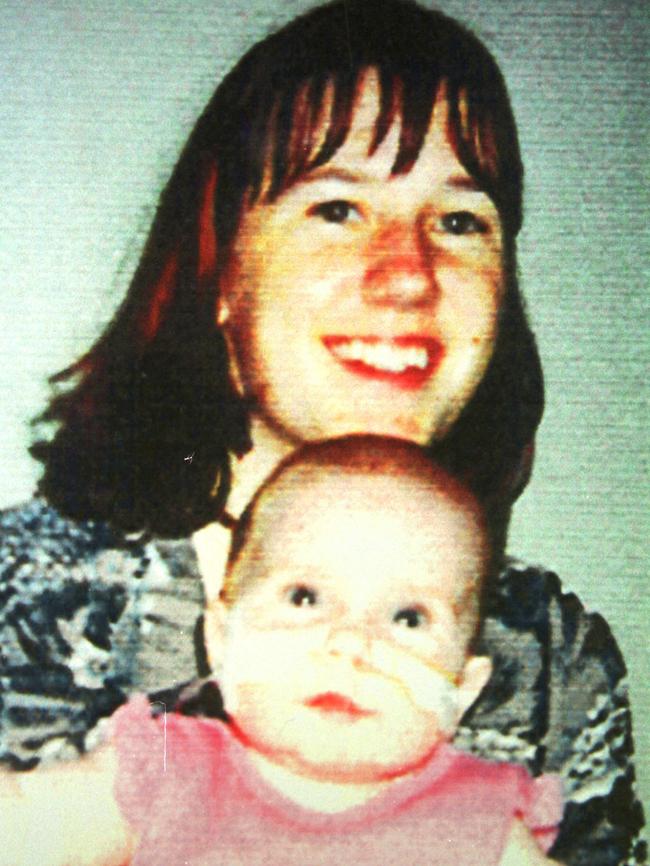

Jacinta came home after a night out, laughing, sounding tipsy. Bush lay in bed, listening to the happiness in her sister’s voice. She’d been through a lot, too: falling pregnant at 17, learning her newborn had a hole in her heart, spending about eight months in Brisbane with Lydia as she endured two open-heart surgeries and fought for life, twice being told the little girl might not make it through the night, the worry and stress contributing to the end of her relationship with Luke Paterson.

Now that Lydia was improving, Jacinta was back on the Sunshine Coast and the two sisters and the baby moved into a Maroochydore flat together. “After everything, it was just such a positive time, to be out, to be independent, to have a nice group of friends,” remembers Bush.

But that night in early 2000, Bush heard a male voice in the kitchen. “I had an immediate reaction to his voice,” she says. “Just through the door. A foreboding.” It was Kris Slade, 19, one of Jacinta’s classmates from the TAFE course she’d enrolled in as a stepping stone into the police service. Soon after, he was there a lot. Before long, he’d moved in.

He didn’t raise his voice. He was not aggressive. But something didn’t feel right to Bush about her unwanted flatmate and his relationship with Jacinta. He seemed manipulative. Jacinta, the quieter of the sisters, became more reserved. She stopped doing things with Bush, always saying she’d wait for Kris. He became possessive: if Bush was playing with Lydia, he’d wait until she got up to do something, then spirit the baby into his room. “Subtle things like that, where you just think, ‘Dude, what’s going on?’ ”

But after Slade “really flipped his lid” at Jacinta one morning over breakfast, Bush decided it was time for him to move out. His anger, never unleashed before, was out of proportion. He’d booked dinner and a motel for that Saturday night but Jacinta had just learnt an old friend was going to be in town and she asked if they might postpone the evening. He yelled, told her he never asked for much, and wore her down but, on overhearing the row, Bush made a decision: “I’m going to get Jacinta alone and say, ‘This is not OK, he’s moving out’.”

He murdered Jacinta at that motel early the next day, July 30, 2000. He stabbed her 41 times with a fishing knife, then tied a piece of rope around his neck and threw himself off the sixth-floor balcony of a Mooloolaba hotel. The rope broke.

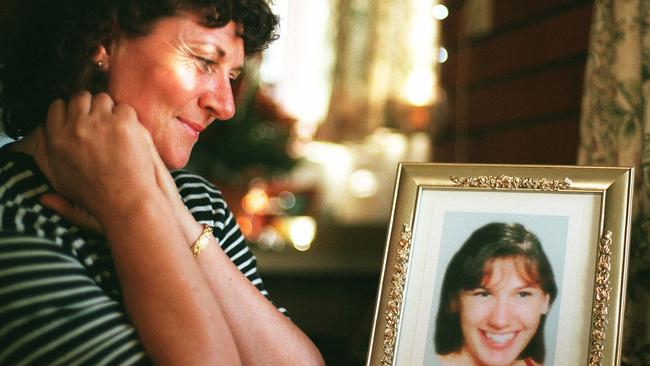

From then, everything was a blur for Bush: the animalistic howl that erupted from her when Robert told her Jacinta was dead, the police arriving, the visit to the hospital to identify her. Seeing the devastation on Robert’s face in that room. The way the tightly bandaged body didn’t look like Jacinta at all and how for one brief moment Bush thought, it’s OK, it’s not her. Then noticing that front tooth Jacinta had always hated. The finality. The anger.

“Rage, like I’d never felt,” she recalls. “I wanted to kill him. I wanted to kill him.” To think that he’d handed Lydia over to Robert the night before and said, “See you tomorrow”. “Knowing full well we never would,” Bush says. “It was planned. At sentencing (in 2003, to life imprisonment, after he pleaded guilty) it came out he’d intercepted a letter from Jacinta to Luke, her trying to reconcile about a month before. (Slade) had tried to get a handgun, he had newspaper clippings of murder-suicides. He took the knife, he took the rope. He knew exactly what he was doing.”

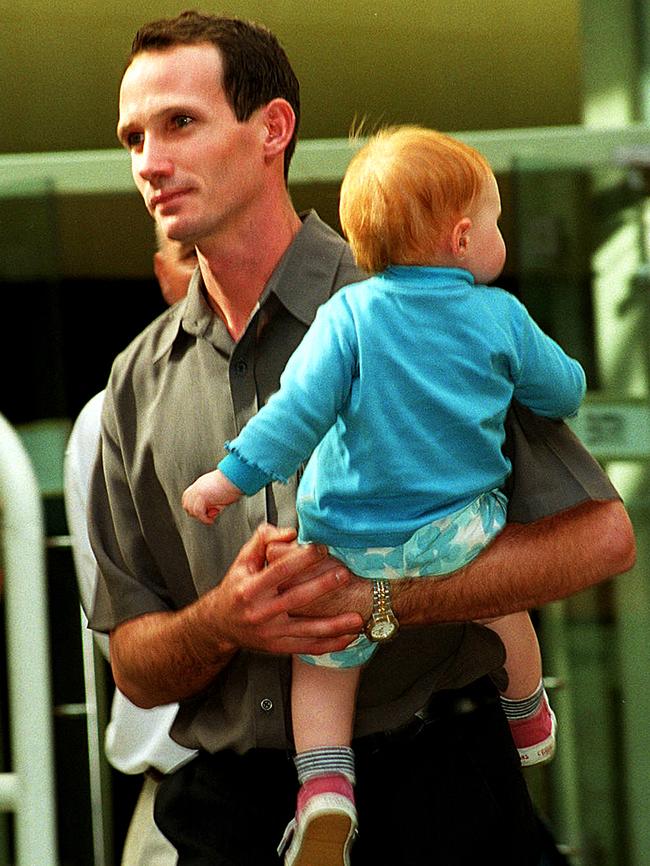

Bush spoke at Jacinta’s funeral, as did Luke. The raw grief was compounded by the tough question: what happens to Lydia? The question ended up in the Family Court. Bush says Robert knew Lydia well, having spent a lot of time with Jacinta and her while she was in hospital, as well as on the Coast. Luke’s contact had been much less. The court granted Robert temporary custody, with visitation rights to Luke. After six months, the decision was to be reviewed with the likelihood Luke would get custody and Robert gain visiting rights. Bush says she has no doubt – “No doubt, at all” – that Robert felt Lydia eventually should be with her father. “The ultimate goal was to reunite Luke with Lydia but right now, she needed what she knew.”

Bush says the Paterson family was never OK with that. “We’d get phone calls from them, harassing and threatening.” Robert had felt intimidated by Travis on other handovers of Lydia. Bush and Robert had gone to the police about their concerns but she says they were told police could do nothing unless Robert was struck.

That happened on November 14, 2000. Lydia had been visiting with Luke and his family, and Robert and his new partner, Barbara Hanson, arrived to pick her up. To add to the high-octane mix, Marlene was there, visiting Lydia at the Patersons’. Bush wasn’t. Witness accounts varied on the degree of force used but in essence, an argument broke out between Travis and Robert, Travis hit Robert who tried to move up the front stairs to retrieve Lydia, Robert collapsed. On November 18, Robert’s life support was turned off. He was 47.

The trial heard that the ruptured membrane in Robert’s brain was similar to injuries sustained by boxers and was more likely the result of a blow to the head than a fall down stairs. But it also heard, in a redirection by Justice Margaret White, that if it was unforeseeable to Paterson that Bush would die or be grievously injured by the blows, the jury should acquit. It did.

“He didn’t even spend a night in a watchhouse,” says Bush. “He stood up, punched the air like he’d won a final. Looked and smirked and walked out, and oh, I was gutted.

“As a young girl, your dad is your world. He was for me. He was the calm in this incredible crazy storm. He wasn’t well-read, he wasn’t uni-qualified, he wasn’t rich but he was amazing for us. And I felt that nobody saw that. I felt very gutted that this person, who to you was everything, can mean so little to other people.”

Park Rd, Milton, in Brisbane’s inner west, was closed off, huge screens showing the opening night of the FIFA World Cup soccer 2010. As the crowd swirled around her, Bush got chatting to an accountant called Matthew Bashford. There was a spark, they exchanged numbers and soon, Bush knew she’d found love.

“Meeting Matt was like exhaling,” she says. “It was like going, ‘Ah, this is it, this is how it should be’.” And now there is Albie, “just beautiful”. Then there’s Grace and Annie and Ella, now 15, 13 and 11, Bashford’s three “lovely, gorgeous” daughters who moved in with them when Bush was pregnant with Albie. Jason, who is now 29 and working as a mortgage broker, was over at the weekend for Albie’s birthday. “He’s doing really well, we’re back to a sibling relationship, not me as Mum, which is nice.” And Lydia “is beautiful, 17, with hopes and dreams and ambitions”.

Lydia lives in Gympie with the Patersons and plans to go to university. On occasions, Lydia has said things about the death of Robert that don’t gel with Bush’s view but she lets it slide. “My love for her is stronger than any ill feelings I have for (Travis) and that’s what I focus on. I want her to be able to reflect back and go, ‘You know, she never rubbished them’.”

At one point in her long recovery, a therapist gave Bush a mantra: “Be my reason, not my excuse”. It resonated. She could wrap herself in sorrow and anger and have a bloody good excuse for staying in a rut, or she could brace herself and walk back into the world, ready to live. “I didn’t want to give up,” she says. “For Jacinta’s and Dad’s sake, I really wanted this experience to be more than, not less than.”

The traumas of her upbringing – and the fact she’d already reinvented herself once as she left Kilkivan – helped her realise life could get better. “I do feel lucky that I had adversity as a child because I think that primes you to realise there are elements of suffering in life, and it’s about how you react and respond,” she says.

An early response was to join the Queensland Homicide Victims’ Support Group. “I have cried with a lot of families. Sometimes you can’t take any more sorrow, you can’t get past the fact that bad things happen to good people.” In 2007, she became chief executive and developed the One Punch Can Kill campaign. She says it was about this time she started to feel the fog lifting, started to see she could make a difference. “The sort of conversations I was starting to have with the group were, ‘Let’s not be defined by this experience, we as a cohort have amazing wisdom about what led up to our loved ones’ death, what happened after, what can be done better around safety and violence messages’,” she says. “We have lived experience and how do we do something with that instead of just sitting around. I’m not saying rumination isn’t important for healing but it needs to be directed somewhere because otherwise you just live in it.”

Some in the group did not share that mindset, says Bush. “If others normalise your pain, suddenly 10 years have passed and the same people are talking about how hard they’ve had it. I’m trying not to judge, but that’s not for me.”

Enmities bubbled over. In the weeks prior to her beingnamed Young Australian of the Year, she faced accusations – not substantiated – of financial impropriety. When she received the award, she got calls and messages from aggrievedmembers, asking how it was she could be up on stage smiling, questioning her love for Jacinta and her father. It upset Bush then, but not now. She smiles breezily and says, “If you’re not pissing someone off, you’re not working hard enough”.

Today she works with the Office of the Public Guardian and is sought after on the speaker circuit, talking about adversity and resilience. She has a Masters in Criminology and Criminal Justice from Griffith University, and has just launched Kintsugi, a wellness service specialising in post-traumatic growth that brings together specialists such as psychologists, nutritionists and yoga practitioners.

She’s dined with Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall – “There was me, (actor) Toni Collette, Poh (Ling Yeow) from MasterChef and the woman (Carolyn Creswell) from Carman’s Muesli” – climbed Tanzania’s Mt Kilimanjaro and “sat around drinking red wine with (actor) Jack Thompson, talking into the night”.

“I’ve had incredible highs,” she says. “I honestly can say at this point, no regrets. I wish things could have been different but no regrets of how I managed what I’ve had. To me, that’s the pinnacle of happiness.”

More than most, she knows happiness is not to be taken for granted. Neither is her mental health. The birth of Albie gave her so many reasons to be happy … and fearful. “Old trauma stuff came up, and suddenly going, ‘F--k, what if I lose her, I won’t survive this’,” says Bush. She started not sleeping. She could not bear to put Albie down. She would not go near a balcony for fear of dropping her, would not walk up a hill with Albie in a pram in case she lost control.

By the time she was admitted to Belmont Private Hospital with post-natal anxiety, she hadn’t slept for three days. “When I handed Albie over, I was crying and saying goodbye to her like she wouldn’t remember me the next day. I had this really distorted view.” After a month in Belmont, Bush and Albie are doing well. “I’m happy with who I am as a parent,” says Bush. “She’s beautiful and I feel confident.”

Now, she’s negotiating to meet Kris Slade. Bush admits to a slight rise in anxiety since learning he could be released. Is she worried he will seek her out? “I don’t think he will, I have no reason to think he will but then, I had no reason to think he’d kill Jacinta, either.” She wants to calm that nervousness by seeing how he looks now and establishing ground rules. “I can set out all sorts of conditions in the parole application, ask for no contact and he’d be a fool to go around that, but I could be travelling to Longreach and he could be there and we bump into each other. What happens then? Who leaves and who says what? Just a frank conversation around, ‘What’s the protocol?’ ”

If he’s willing, she’d like to know more about him. “There is a curiosity for me in understanding what life has been like for him, what kind of introspection he has around what happened and why. I don’t need to get that, I’d like to get that. I find it fascinating that somebody can come into your life and completely change the whole trajectory for you, yet I know nothing about him.”

Such a meeting would be a final piece in the puzzle that is the remaking of Jonty Bush. She was broken, a mess of jagged, ugly bits. She will never be the same, rejecting the idea that it’s possible to return to who you were before tragedies such as hers. She’s different, but better, just like the kintsugi ceramics that Bush finds so appealing.

There’s a video on Bush’s blog showing this ancient Japanese method of repairing broken crockery. Pieces of a cup have been joined together, the cracks lacquered up. A scraping, rubbing noise fills the soundtrack as a hand repetitively runs a blunt, pencil-like tool over the lacquer, smoothing it down. It’s Bush’s hand but you can’t see her pretty face, just the occasional glimpse of her jagged fringe as she concentrates on the job. Kintsugi means “to repair with gold”; when the cup is finished, the ceramic will be highlighted by fine streaks of the precious metal. It’s a metaphor for how Bush sees recovery after trauma. “These works of art, nobody tries to restore them to what they were and disguise the cracks,” she says. “They actually highlight them and incorporate these cracks and blemishes in the broader story of the piece. That really spoke to me.”

Stunning, despite the damage.