Anatomy of a supercell: Weather expert explains how the highly organised storms unleash

They can last up to eight times longer than regular storms and travel vast distances with its highly organised corkscrew structure wreaking havoc: But how do supercells actually work?

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Thunderstorms can bring a range of phenomena – heavy rain, thunder and lightning, hail, wind gusts and even tornadoes.

Storms or thunderstorms can be unpredictable and can occur with little warning, and can last up to many hours and travel long distances causing damage in their wake to homes and vehicles and cause loss of power, isolation and flash flooding.

As Queenslanders brace for an intense and earlier storm season experts reveal the anatomy of a thunderstorm and the key factors that can turn it into a dangerous supercell storm.

WHAT CAUSES A THUNDERSTORM?

For a thunderstorm to form, three basic ingredients are needed, moisture, a lifting mechanism forcing the air upwards and instability which is where warm moist air at the surface rises into the atmosphere above.

For a typical thunderstorm the updraft transports the warm, moist air up through the storm but as the air cools and condenses clouds of precipitation form, and once this precipitation becomes too heavy gravity takes over and pulls the rain and hail down to the surface with a cool gust of wind.

The cool air interferes with the warm updraft, weakening the storm.

For severe thunderstorms, these three ingredients need to be strong but a fourth ingredient is wind shear.

WHAT IS SUPERCELL STORM?

Queensland can experience what is known as a supercell thunderstorm which is a highly organised storm that lasts up to six to eight hours.

Professor Michael Reeder, a meteorologist and cyclone expert at Monash University said the thing that characterises a supercell is that it is very long lived compared to an ordinary rain event that lasts about 10 to 20 minutes.

“(Supercell storms) are extreme but relatively rare forms of precipitating convection (rain clouds),” Prof Reeder said.

Supercells generally produce lots of hail and occasionally tornadoes, with the potential to cause serious damage.

“It’s a single cell, a single convective storm, which is quite large. Maybe a fifth of them might produce tornadoes, they usually produce large amounts of hail,” Prof Reeder said.

“Supercells are relatively rare, we don’t get a lot of them and even in the US, which is the supercell capital in the world, the majority of the storms are not supercells.”

WHAT CAUSES A SUPERCELL STORM?

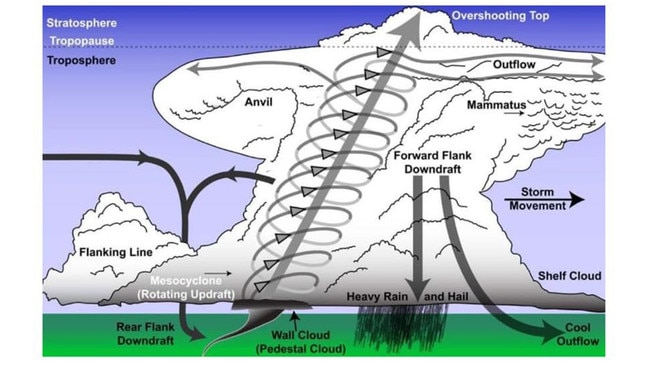

Supercell storms have a deep rotating column of air, which tilts away from the down draft.

Windshear is also a factor. This is the increasing speed and height, as well as a change in direction as the storm moves up through the atmosphere.

The reason why wind shear is important when it comes to severe thunderstorms is because it leads to a tilting and rotation of the updraft into a sloping corkscrew structure.

This organisation means that cool downdraft is separated from the warm updraft, so the storm doesn’t weaken like in a regular thunderstorm.

WHERE DO SUPERCELL STORMS OCCUR?

Some areas produce more supercells than others and it all has to do with geography, Prof Reeder said.

“A good example is the central US. It has to do with geography. There, warm moist air is transported northward near the surface from the Gulf of Mexico,” Prof Reeder said.

“Drier colder air from the Rockies is transported over the warm moist air. This configuration of colder and drier air on top of the warmer and moister air is unstable and drives the convection. A second crucial ingredient is the way the winds change with height. This happens to be favourable in that region: low-level southerlies (wind from the south) turning aloft to westerlies (from the west).

“This favourable region in the US is colloquially called tornado alley. The term is used colloquially around the world now.”

QLD’S BRUTAL DECEMBER STORMS

Prof Reeder said the closest proximity of “storm alley” would be southern Queensland, North New South Wales, in that sort of region we have the warm, moist air from the ocean.”

In January climate scientist and meteorologist Bruce Harper said tornadoes in Queensland, especially in the southeast region, are fairly common and typically strike during December to January period.

“They are more common than the average may think, some suggest that once a year we can have one ‘tornado-day’ in the southeast of Queensland,” Mr Harper said.

Mr Harper referred to the Gold Coast Christmas weather event that was deemed not a tornado, but rather an entirely unique type of destructive storm.

“When the situation is right, much like it has been recently, with the concentration of severe storms or cluster storms especially if they are supercells then they can develop these tornadoes.”

Experts said the likely cause of the Christmas Day event was straight line winds in what was likely a derecho storm event event.

A derecho is a straight line wind storm is created by a fast moving group of severe thunderstorms which could include “embedded vortexes” – where a rotating column of air and water occurs.