When John and Julianna Ho decided to open a Chinese restaurant in Walgett in the 1960s, friends thought they were crazy.

“People basically said who’s going to want to eat Chinese food in a small town where there’s nothing but heat and dust and flies,” said son Chris Ho.

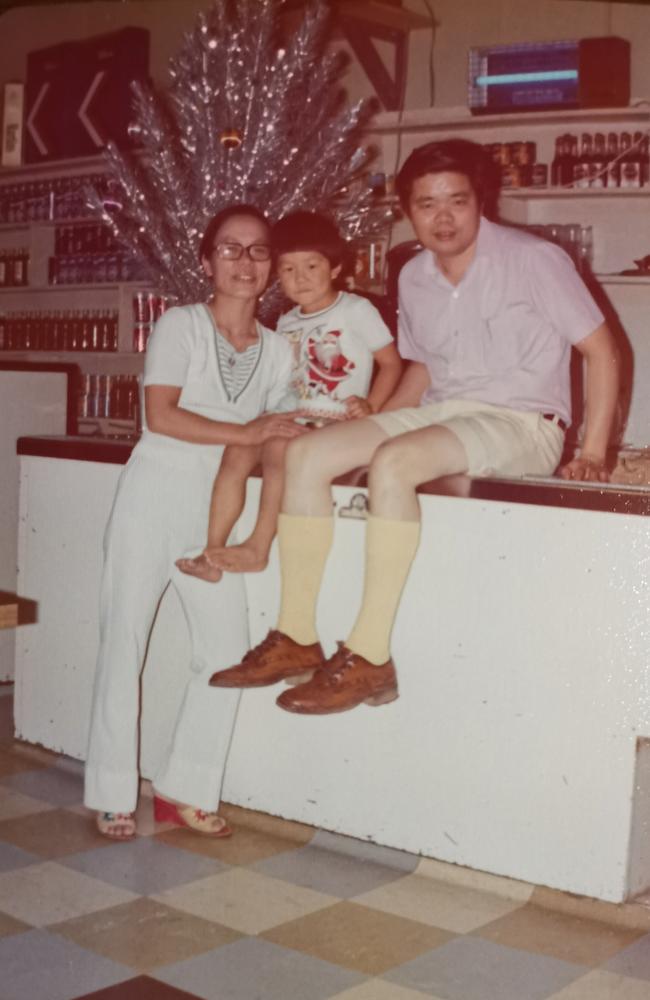

But with a couple of suitcases in their beat-up car, the young family drove 650km from Sydney to the outback NSW town and set up shop in an old Greek milk bar.

The “only Chinese family for Cooee”, the Hong Doo Cafe opposite the cop shop, post office and courthouse fast become a focal point in town.

“I’m sure fried rice or chicken chop suey and sweet and sour pork were totally novel and exotic delicacies for the townsfolk at the time,” said Mr Ho.

In the 60s, Chinese restaurants were on their way to becoming suburban icons in Australia and by the 1970s, it seemed every country town had one too.

From Wagga Wagga to Walgett, young families, many recently arrived from southern China and Hong Kong, struck out to build a life for their families, creating the old-school Chinese restaurants we’re now so nostalgic for.

Today, many of us fondly recall their steaming plates of ‘Aussie-Chinese’ dishes like lemon chicken, sweet and sour pork and fried ice-cream served on lazy Susans.

Childhood birthdays, anniversaries, even marriage proposals were celebrated in these local eateries that broke the monotony of meat and three veg, broadened our palates and sparked an interest in cultures beyond the boundaries of our suburbs.

And for the children who grew up in those restaurants, that time remains equally vivid.

ONLY CHINESE FAMILY FOR COOEE

When the Ho family landed in Walgett, the nearest Chinese restaurant was 100km away in Coonamble and summer temperatures could soar above 40C.

For Juliana, a cosmopolitan Hong Kong girl who had met and married John in Sydney, “being plunked in the middle of nowhere” was quite a culture shock

“If you can picture the guys in Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, when they hit Broken Hill. Well, you can imagine my mum doing the same thing when she arrived in Walgett,” Mr Ho said.

Despite their isolation, the family was embraced by the town. The local police taught his mum to drive and his dad would help sandbag the town when the rivers ran high.

“I have happy memories of playing with all the local kids, white and indigenous, at the local pool, so it was quite a harmonious environment for me as a young child.”

Hong Do, which means ‘fragrant place’, served both Aussie and Chinese meals that catered to local tastes and adapted to available ingredients.

“You had to straddle the fine line between tickling their tastebuds and giving them what they wanted. It wasn’t an option for them to do, you know, the really authentic stuff.”

Mr Ho still has a soft spot for those old-school recipes — he’ll gleefully tuck into sweet and sour pork, curried prawns and shredded beef. And he has plenty of pride in his parents.

“They’re just people who struck out and decided to have a go and contributed in their own small way to the culinary life of the country,” he said.

A TOUCH OF CLASS

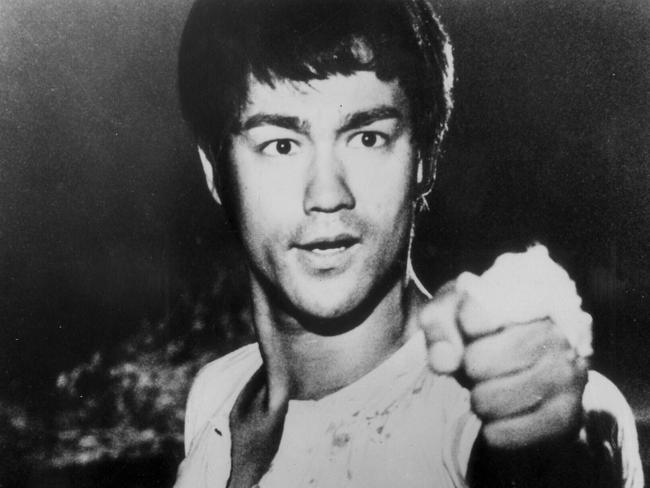

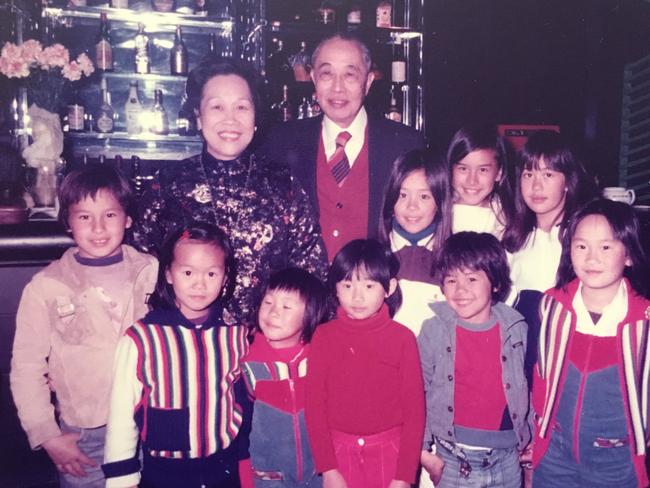

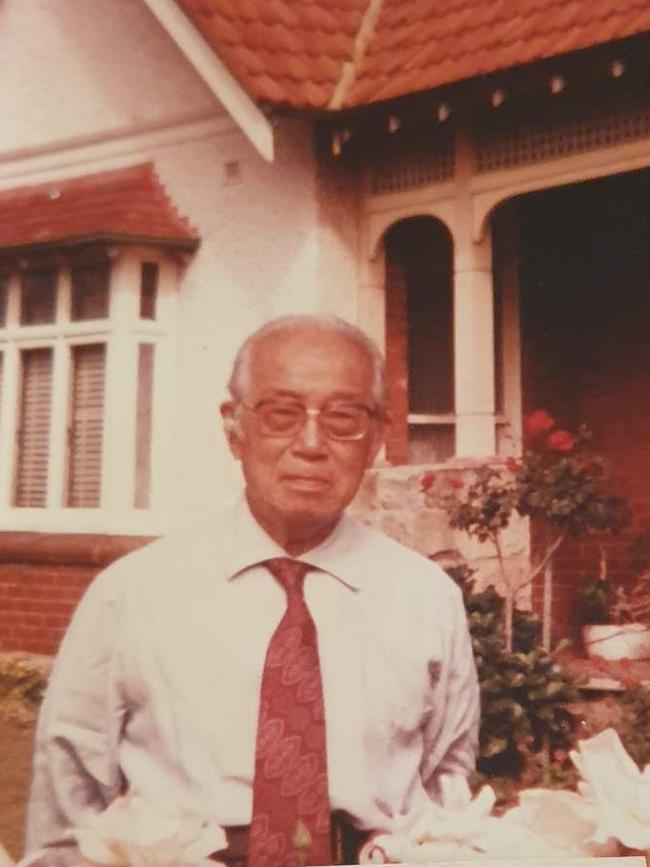

In the 1970s, Martin Kwok brought the bling to suburban Chinese dining in Sydney but before he became a restaurateur, he was getting into trouble with Bruce Lee.

Mr Kwok grew up in Kowloon City in Hong Kong where the pair went to Catholic school, and Lee would whistle outside his room at night so they could sneak out.

“They used to both get up to mischief,” said his daughter Juanita Kwok. “So Bruce Lee got packed off to San Francisco and dad got sent to Sydney to get them away from bad influences.”

In 1961, Martin – then Kwok Chin Man – arrived alone in Sydney with a few distant contacts. The White Australia policy was in place so his grandfather got him in on a sponsored business visa. He took the name Martin and began his new life.

Following in the footsteps of earlier Kwok men who travelled from the village of Chuk Sau Yuen to work in Australia from gold rush times, Mr Kwok got a job at Chequers nightclub run by the Wong brothers before opening his first restaurant.

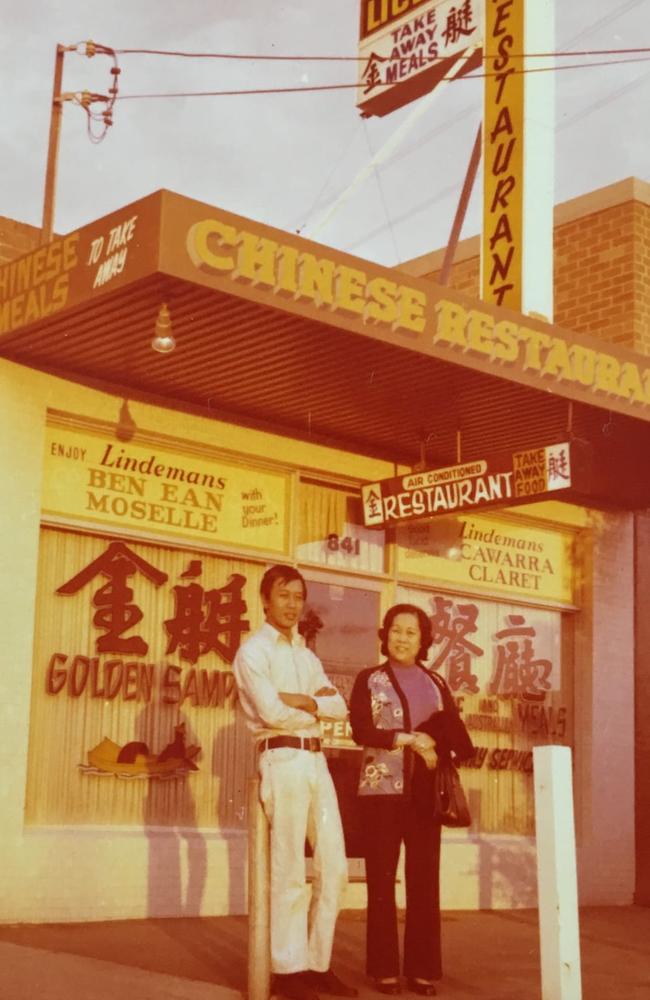

The Golden Sampan opened in Carlingford in the 1970s but Martin Kwok was already thinking bigger.

“He didn’t just want a suburban restaurant, he wanted something grand,” said Ms Kwok “So he worked hard and saved up and then he realised his dream by getting an architect to design the Nightingale restaurant on New South Head Rd in Edgecliff and no expense was spared.”

From the Chinese-tiled roof to the imported crockery and Dragon Shaped chopstick holders, Mr Kwok’s flair was baked into the extravagant multi-level restaurant.

It was the very best of Hong Kong style dining and attracted the elite of Sydney.

“He was a very stylish, ambitious person. He just put everything into this restaurant. So it was just the most amazing restaurant. And the food was incredible. ”

Out of the kitchen came soups served in intricately carved winter melons, platters of cold meats and jellyfish in phoenix shapes and exotic ingredients like beche-de-mer.

Mr Kwok’s success enabled him to sponsor his parents and sisters to come out to Australia and his own father often sat downstairs doing accounts on his abacus.

With five kids at school and a growing extended family, Mr Kwok was an indefatigable entrepreneur, and after Nightingale closed, he opened a French-style restaurant, contributed to cookbooks, even created White Wings’ first Chinese frozen food range.

“He had a lot of responsibility on his shoulders,” Ms Kwok said. “But I’m totally proud. I just have such fantastic memories and it’s such a big part of me.

“And I still have a bit of a sense of sentimental attachment to some of the staples like beef in black bean sauce and sweet and sour pork. I still love prawn cutlets. I’m guessing that’s an Aussie Chinese invention!”

AN ELEGANT ADDITION

CHINESE food has been part of Australia since the gold rush, but it wasn’t until the first half of the 20th century that Anglo-Australians began fully embracing it.

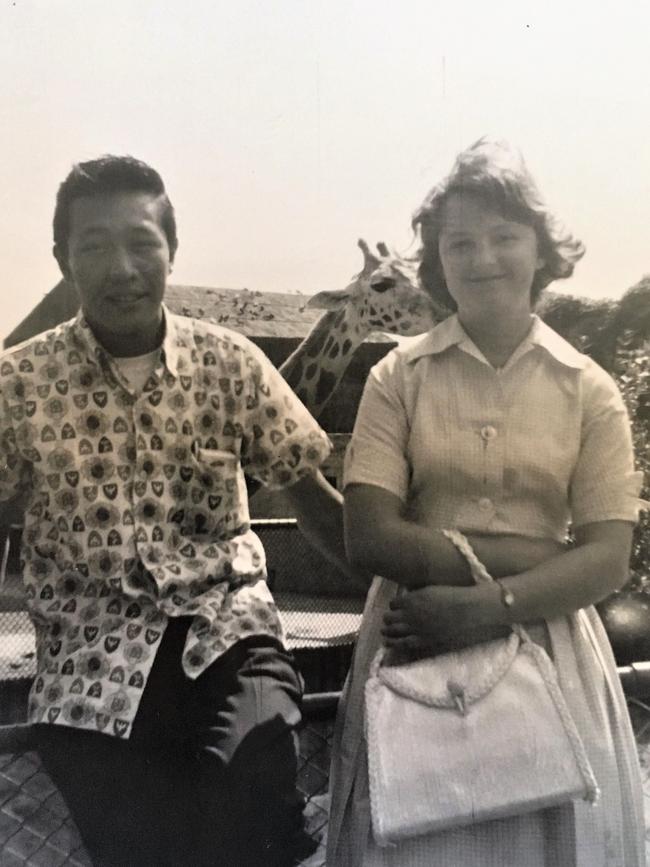

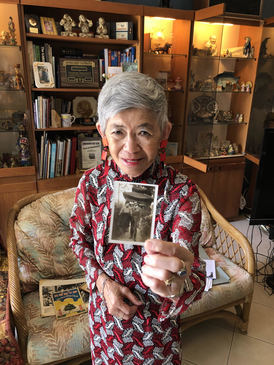

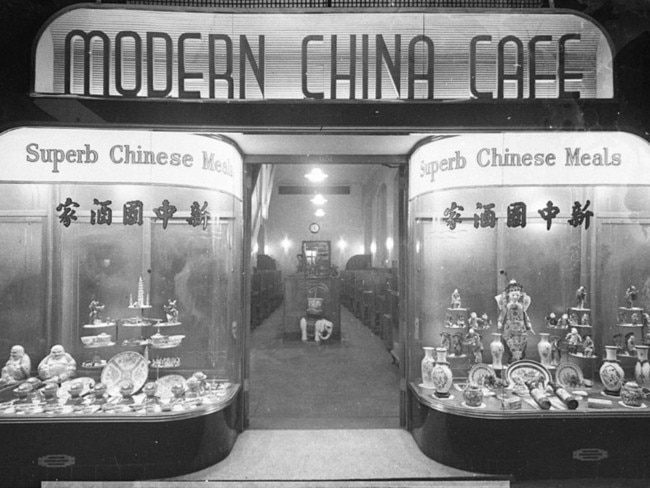

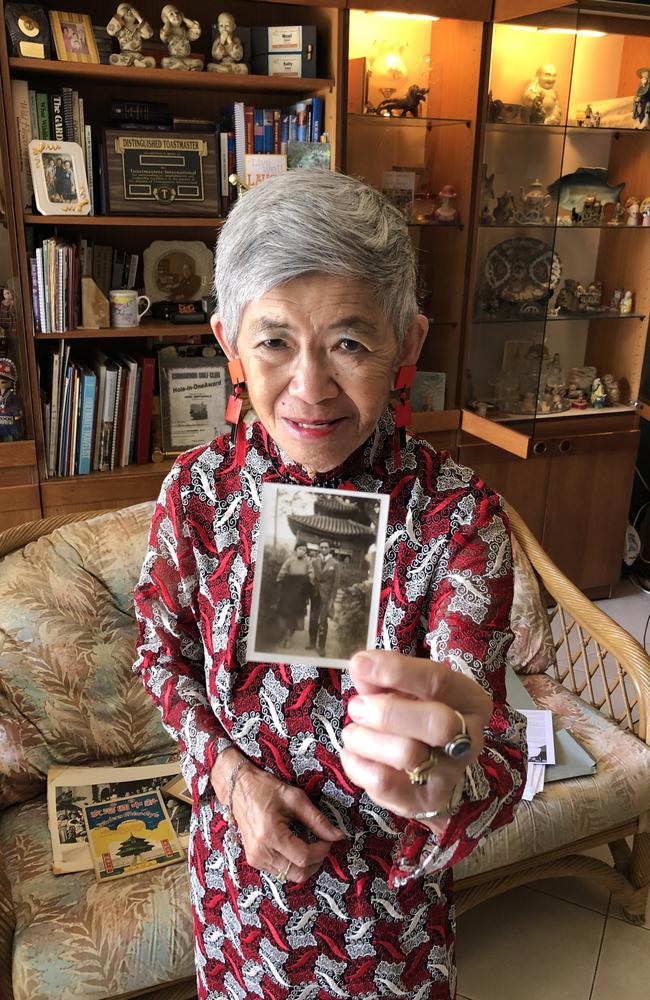

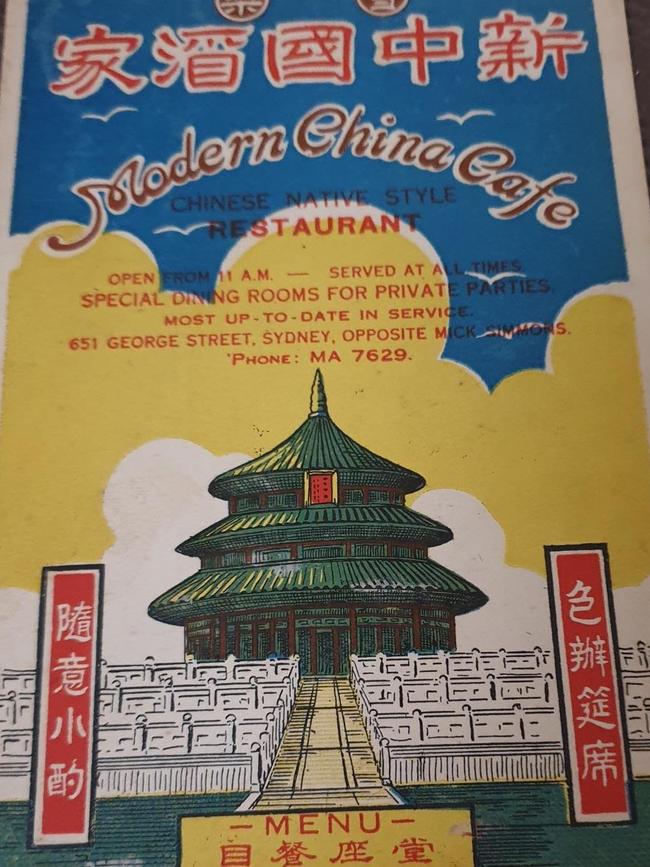

In 1939, when Sally Rippingdale’s dad opened his elegant Modern China Cafe at 651 George St, Sydney, there was just a handful of Chinese cafes around.

Hung Jarm Pang commissioned an beautiful Art Deco shopfront to serve his “superb Chinese meals”, filling its windows with ornaments from China creating a magical display.

Cooks and waiters from Canton lived on the third floor, and Mr Pangs seven Australian-born children worked after school in the cafe which backed onto Hay St’s produce stores.

“My father was involved in the White Australian policy, where to stay in Sydney you had to have a business. So he started an import-export business with Modern China Cafe tea and the ornaments, and then the cafe business prospered,” she said.

For Chinese restaurants to survive under the discriminatory government policies, owners had to provide food that didn’t directly compete with white establishments, but would still suit Western tastes.

Staples like sweet and sour pork, chow mien and dim sims became popular at this time and Mrs Rippingdale’s still has the ‘Aussie-fied’ recipes from her father’s cafe.

“We adhered to the Western taste in regards to the menu which was quite extensive. We also had the Chinese menus for the Chinese people who came into the cafe.

“We also had a lot of soldiers and sailors come in. It was a basic interior, laminated tables and the favourite combination was short soup, fried, rice and sweet and sour pork.”

The war years drove a new appetite for Chinese food, not only the Cantonese delights dominating local eateries, but well-travelled servicemen sought more authentic cuisine.

Regional dishes from every corner of China can now be found in Sydney, but restaurants like Mr Pang’s helped pave the way for the vibrant food culture enjoyed today.

Those early dishes are part of Australia’s culinary history, said Mrs Rippingdale, “as distinct as meat pie and sauce” with many still on the menu at country and suburban restaurants.

“We were one of the first food cultures (Australians) acclimatised to. Now we’ve got all this wonderful Italian, Lebanese, Japanese, but we were the forerunners because of our ancestors who came from China,” she said.

“Chinese cafes played a huge role for families all over. We’re very proud to be part of that culture and to open up the Chinese cuisine to Sydney.”

* The author thanks Michael Williams and the Chinese-Australian History Society for assisting with this article.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Police Minister blames Border Force for flood of cocaine

Police Minister Yasmin Catley has taken an extraordinary swipe at Australian Border Force, blaming it the prevalence of cocaine in Sydney.

Last-ditch move to save gold mine as Greens slammed

The environmental impacts of the proposed mine were discussed in depth at a Greens-moderated online meeting this week, the reasons behind the Indigenous heritage laws being triggered were barely touched.