Why we all owe former Labor premier Wayne Goss a debt of gratitude

Sacking a worker for being gay may now appear absurd to most Queenslanders yet, along with discrimination against women or the right to protest, the matter was not so clear-cut in 1991. That it’s clearer now, is largely thanks to one former premier, writes Michael Madigan.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sacking a worker for being a homosexual may now appear absurd to most Queenslanders yet, just 30 years ago, the matter was not so clear-cut.

Thirty years ago, it was quite possible an allegedly “promiscuous woman’’ could be discriminated against in the workplace, or a public protest be cancelled because such assemblies could be deemed unlawful.

The release of the cabinet papers from 1991, extracts of which were published in The Courier-Mail, once again provides us with those important legislative milestones recording our evolution as a society and reminding us how dramatically communities can transform in a relatively short span of years.

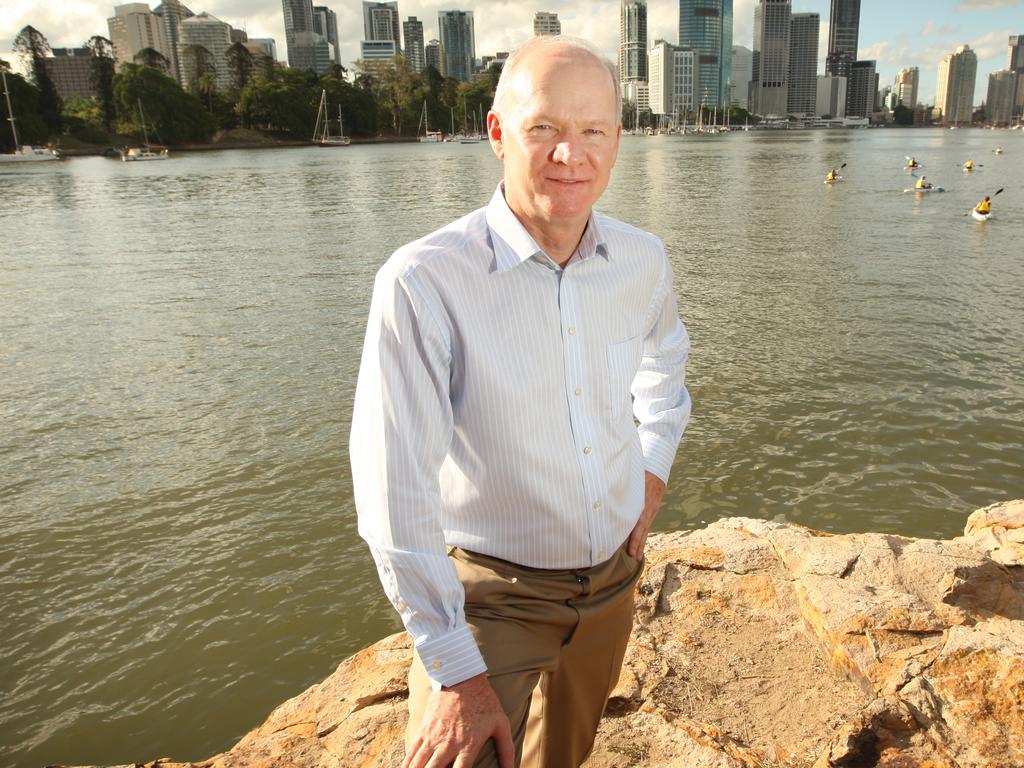

That the state owes something of a debt to former Labor premier Wayne Goss is widely accepted across the political spectrum.

Goss, who won power in 1989 after decades of rule by the old agrarian-inspired Country Party which morphed into the Nationals, took on an ambitious program of reform which modernised Queensland.

Many could argue, with some legitimacy, that Goss’s legislative ambitions were in some ways an opening act to the present day malaise of identity politics, an overly obsessive focus on environmentalism and the more extreme elements of “fourth wave’’ feminism which can find acrimony and disharmony between the sexes even in the most mundane transactions of social and professional life.

Yet an examination of the cabinet papers reveals the still rookie Labor government of 1991 was merely bringing the state in line with a rapidly changing international landscape which was becoming less punitive, more inclusive and far more aware of the value of our natural environment.

The horrors of Queensland’s prison system were then encapsulated in the name “Boggo Road”, a prison built in the late 19th century which carried with it the whiff of our convict origins, and containing a notorious “black hole’’ under the oval where prisoners served solitary confinement.

It was only in 1991, following the Kennedy review of corrective services, that the Goss Labor cabinet finally decided to rid the state of that monstrosity which closed the following year.

That lawful sexual activity could be used as grounds of discrimination in the workplace was rejected, protecting not only gay people but women who could still be discriminated against because of an allegedly “promiscuous lifestyle”.

That more coherent approach to the role of women in the Queensland workplace was built upon by Goss’s attorney-general Matt Foley.

Foley, installed as AG in 1995, challenged a century-old culture inside the state’s legal establishment, making it clear he would open up avenues for more women to be appointed to the bench.

It was a change in culture which led to such appointments as our present day Chief Justice Catherine Holmes, AC, to the Supreme Court in 2000.

As University of Queensland political historian Dr Chris Salisbury points out in his review of the 1991 Cabinet Minutes, it was only in that year of 1991 that Queensland fully reasserted the right to lawful protest.

The Electoral and Administrative Review Commission (a recommendation of the corruption-busting Fitzgerald Inquiry between 1987 and 1989) delivered a report arguing that our public assembly laws ran counter to internationally recognised civil and political rights.

It took the then environment minister, Pat Comben, to spearhead new nature conservation laws and recognise acts of “environmental vandalism”, and it took the Electoral and Administrative Review Commission (another recommendations of the Fitzgerald Inquiry) to prompt the eventual disbanding of the gerrymander created back in 1949 by a Labor government. Significant changes in a political culture are never trouble free and can fire a revolutionary fervour amid certain individuals whose enthusiasm for radical transformation can eclipse original intentions and sometimes even threaten the worthwhile and sensible advances that can be made.

Any Queenslander who witnessed the rise of One Nation in the 1990s and listened carefully to party leader Pauline Hanson’s maiden speech to federal parliament in 1996 could hear the distinct roar of widespread electoral frustration and anger at much of what the Goss government stood for, from Indigenous land rights to economic rationalism.

Yet, looking back across three decades, it becomes apparent that the Goss government was hardly a radical one.

It merely ushered in a state reflecting a more sophisticated and progressive world, legislating accordingly in a manner few would now find confronting or unreasonable. Goss, who died in November 2014, kept a relatively steady hand on the tiller as he sailed the Queensland ship of state into the 21st century, and for that we should be grateful.