The mid-1980s were the time to be a police reporter in Queensland – if you were brave enough

IN 1986, the police round was assigned to cadet journalists but police response to a report critical of the traffic branch was a sign of bigger things to come.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN THE offices of The Courier-Mail in the mid-1980s – think long corridors of linoleum, cigarette smoke, early model word processors with a green screen – it was the tradition to assign young, wet-behind-the-ears cadet journalists to the “police round”.

There, amid the motor vehicle fatalities, the deadly domestic disputes, the industrial accidents and house fires, reporters could “cut their teeth” on the rough and tumble of the newspaper game.

Often, you were required to work a late shift and you sat at the back of the reporters’ room beside the large black police radio scanner waiting, like a fisherman, for a bite of information that might make a news story.

Those were the days when fatal car crashes made page one, so it was an important round. And God help you if you missed a story that was captured by The Telegraph and other Brisbane rivals.

It was a time, too, before the advent of public relations machines that spun walls of protection around government ministers and other important public figures.

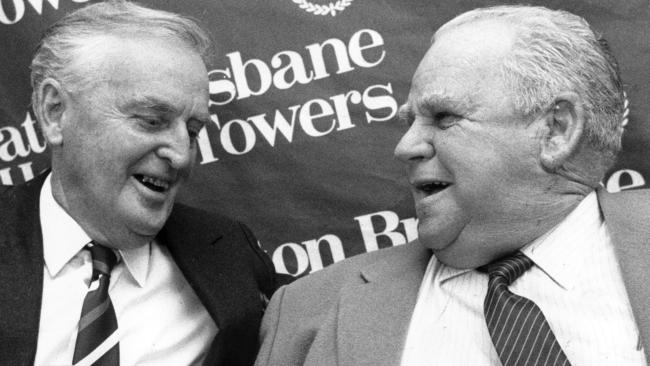

I had, in my old contact book, for example, the home numbers of premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, his deputy and (in 1986) police minister Bill Gunn. And I had police commissioner Terry Lewis’ home number up at 12 Garfield Drive in Bardon.

While some journalists tolerated the police round as a stepping stone to more lofty arenas – state political reporter or the ultimate, “feature writer” – I loved the urgency and excitement of it, and that you never knew what each day might bring.

I knew nothing of any police corruption, though the rumours persisted permanently like some annoying white noise. And while I simply reported the facts of incidents, the police I dealt with were, by and large, helpful and as eager as we were to publish stories as accurately as possible.

It wasn’t until around August 1986 that everything changed for me.

I had been given a tip-off from a source in the Traffic Branch that the force’s newish random breath testing initiative – hailed by the department as a groundbreaking, indeed lifesaving, component to day to day policing – wasn’t only the opposite to the public spin, but that the branch had been sending out falsified statistics into the public domain.

The reality was, not a single random breath testing unit had yet been put out on the road.

The story ran on page one in The Sunday Mail on August 17, 1986.

In writing that story – one that made the Traffic Branch look foolish and the police force in general deceptive – I had crossed an invisible line. I had reported facts the Queensland police did not want revealed.

The following day I received a phone call from a senior officer in the Traffic Branch (he would go on to be named as corrupt at the Fitzgerald Inquiry in just a few years) asking why I would write such a story.

“I thought we were friends,” he said to me, though I had never met him in person.

He would go on to ring and harass me both at work and on my private home number, so much so that I had to leave the phone off the cradle.

In the month that followed the page one story, I woke one morning in my rented cottage in Taringa to find the four tyres of my car let down. Had it been unhappy Queensland police?

I would also be pulled over by unmarked and marked police cars on several occasions for fictitious traffic infringements and vehicle defects.

As this minor needling was happening, Four Corners investigative journalist Chris Masters was starting his inquiries into Queensland police corruption and The Courier-Mail’s Phil Dickie was about to prepare a suite of stories on the same subject.

Although relatively harmless, the police harassment played a small but important part in my decision to leave Queensland and try my luck as a journalist down at the big smoke in Sydney.

Living in a state where an individual’s rights were paramount, where culture was treasured, where difference was not only tolerated but encouraged, after Queensland it was as if I had moved to another country. I wouldn’t return for almost 20 years.

With hindsight, making the move was bad timing on my part.

Just months later, as I settled into a rented terrace (a former brothel that was, unfortunately, still listed in some disreputable newspapers, resulting in innumerable late night knocks on the front door) in Sydney’s Surry Hills, the Dickie stories were rolled out, and in May 1987, Masters’ The Moonlight State report went off like an atomic bomb.

I missed all the fun. And from that considerable distance, too, I had watched, with a small degree of satisfaction, the fall of Bjelke-Petersen and his corrupt regime.

Today, I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else but Brisbane.

But if you listen carefully, the tremors from that ghastly period in the state’s history can still be sensed and on occasion, the sins of those fathers are still around us. If we drop our guard, even for a moment, history might repeat itself.

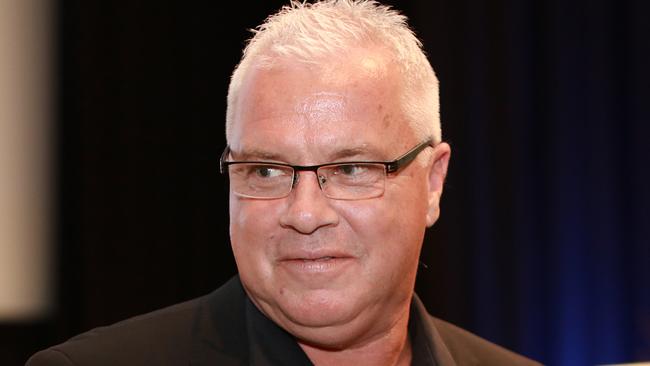

Matthew Condon is the author of the Three Crooked Kings trilogy and its companion volume Little Fish are Sweet.