Opinion: Qld media shield laws don’t go far enough

Fifty years on from Watergate, Queensland is only now catching up on laws to protect journalists – but still hasn’t gone far enough, writes Peter Gleeson.

Peter Gleeson

Don't miss out on the headlines from Peter Gleeson. Followed categories will be added to My News.

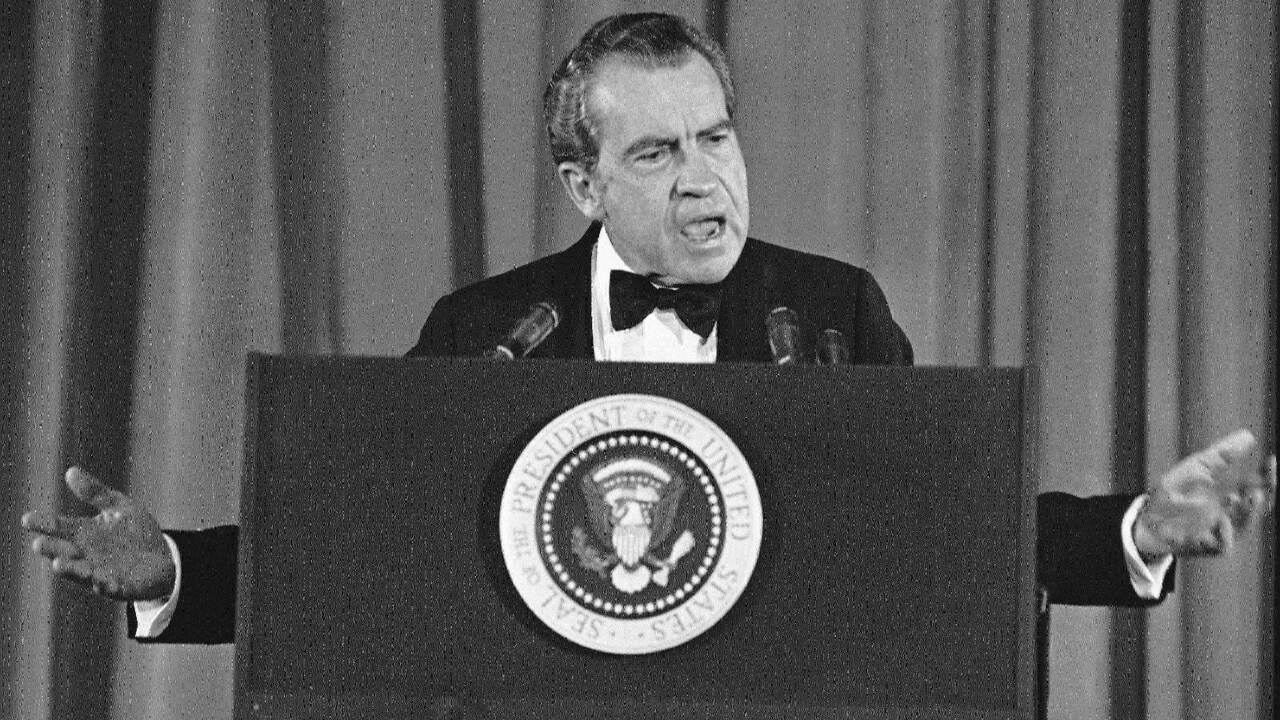

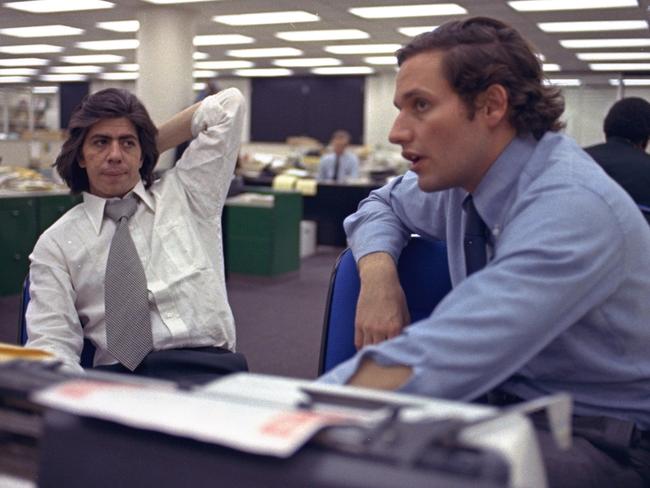

When The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein broke the Watergate story – which led to US president Richard Nixon’s downfall – they had a primary source who would later be identified as “Deep Throat’’.

In 2005, 31 years after Nixon’s resignation and 11 years after his death, a family lawyer identified former FBI associate director Mark Felt – then suffering dementia – as Deep Throat.

Woodward and Bernstein confirmed the attorney’s claim. Had the Felt family not decided to go public, it is undeniable that Woodward and Bernstein would never had made the informant public.

Such is the code of journalism. Good journalists never give up their source. It is a fundamental tenet of how the Fourth Estate does its business.

If whistleblowers know they can trust a journalist with sensitive information, they are much more likely to be forthright and frank. It underscores our democracy and it keeps the bastards honest.

In 1987, The Courier-Mail broke the stories that resulted in the Fitzgerald inquiry, which brought down the Bjelke-Petersen government, because brave people told journalistPhil Dickie information and they trusted him.

If only the much-maligned Crime and Corruption Commission respected the role of good journalism. The CCC is a spectacular failure and Tony Fitzgerald, QC, who recommended a corruption watchdog from his first report, must be livid with the way it has lost its way.

The CCC in Queensland has become the schoolyard bully of the Queensland judicial, political and media landscape.

Let’s go back to September 2008, when civil libertarians were attacking an “utterly obnoxious” move by the Bligh Labor government to strengthen the powers of the state’s corruption watchdog.

The Queensland Council for Civil Liberties raged that the Bligh government had scant regard for public concern if it went ahead and bolstered the coercive potency of the Crime and Misconduct Commission, the precursor to today’s Crime and Corruption Commission.

Brisbane solicitor and QCCL vice-president Terry O’Gorman warned the CMC would become a law unto itself, while media industry chiefs and the opposition labelled the move an attack on democracy. But what was sparking the outrage?

The CMC was calling on the government to amend its legislation to force witnesses at secret hearings to answer questions or face jail – after the law had been successfully challenged in the Supreme Court by a witness known only as “D”, who refused to give evidence on the grounds it would incriminate him.

Despite the outcry, the Bligh government duly closed the legal loophole, with premier Anna Bligh describing the amendments to section 192 of the Crime and Misconduct Act as simply a “legal technicality”.

A few weeks later, attorney-general Kerry Shine went on to assure parliament that no journalist had been asked by the CMC to reveal their sources.

“I’m advised that the CMC policy is to not call journalists to hearings as to reveal their sources,” Mr Shine declared.

A cynical Mr O’Gorman retorted: “A promise from a politician isn’t worth the paper it’s written on”.

Why? Witness D was a television journalist, and a few weeks later, was hauled back before a CMC star-chamber hearing and interrogated.

Once again, he was threatened that if he didn’t reveal his source – a direct contravention of his profession’s ethical code – he would be jailed for contempt. Once again, he refused to answer questions because it could incriminate him.

Thankfully, Witness D – who to this day still can’t be identified because of a strict gag order – escaped jail time, but he’s written previously in this paper about the investigation’s devastating and ongoing impact on his life.

“I was forced to suffer in silence for nearly two years,” he wrote.

“By law, I couldn’t even tell my wife and family what was happening. My nerves were shot. I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

“Surely, Tony Fitzgerald QC would never have imagined that the corruption body he recommended be set up in Queensland to fight organised crime, would be using its investigative powers against journalists.”

Disturbingly, 14 years on, it’s happening again – with the case of Journalist F. Like Witness D, he’s a television journalist whose identity has been suppressed, he’s being forced to face coercive hearings – and his refusal to betray the trust of a contact by naming names means he’s facing jail time. According to a previous Supreme Court case, Journalist F received a tip-off from a police officer in 2018 about an impending raid on the home of a murder suspect, who was also the subject of a joint counter-terrorism investigation. The corruption watchdog hauled Journalist F into a star chamber hearing where he argued he did not have to answer due to a “public interest immunity”.

Last November the Queensland Court of Appeal upheld a decision by the Supreme Court judge who found public interest immunity did not extend to protect a journalist’s confidential sources – meaning Journalist F is set to be hauled back before the CCC and threatened with a $26,690 fine or five years in prison if he continues to refuse to answer questions.

Unfortunately, if Journalist F had been hoping for intervention from the Palaszczuk government – which gave a commitment before the 2020 election to provide better protections for journalists, then he’d be bitterly disappointed.

In May, Queensland became the last Australian jurisdiction to pass media shield laws protecting reporters from prosecution when they refuse to name sources in court proceedings – but Attorney-General Shannon Fentiman stopped short of extending the safeguards to the CCC.

In fact, government MPs voted down an amendment moved by LNP shadow attorney-general Tim Nicholls to protect reporters from CCC prosecution, with Mr Nicholls telling Parliament: “A key pillar of a robust democracy is a free media.”

Ms Fentiman says the government is considering expanding the laws to include the CCC, but that’s cold comfort with Journalist F because any amendment is still months away and is unlikely to be retrospective – meaning he must face the music, and yet another star-chamber hearing, possibly as early as this month.

As a journalist since the 1980s, I know how vital it is to prevent journalists being jailed for simply upholding the trust of their sources.

Here’s what the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance says: “Journalism plays an important role in democracy – the journalist is responsible for holding the powerful to account and shining a light on the injustices. To further penalise journalists who are doing their job is an attack on the community’s right to be informed. A Queensland journalist faces further court action for protecting a confidential source right now. The protection of sources is a fundamental responsibility for ethical journalism.”

The CCC want blood because a journalist dares not answer a question. It is a disgraceful abuse of power and a damning indictment on a government that talks a big game on protecting the Fourth Estate, but instead, squibs it once again.