Opinion: Indigenous Voice to Parliament too important to rush

Most Australians agree an Indigenous Voice to Parliament is a good idea, but Paul Williams says it shouldn’t be rushed.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What is the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, and what chance does a referendum to install it have of passing any time soon?

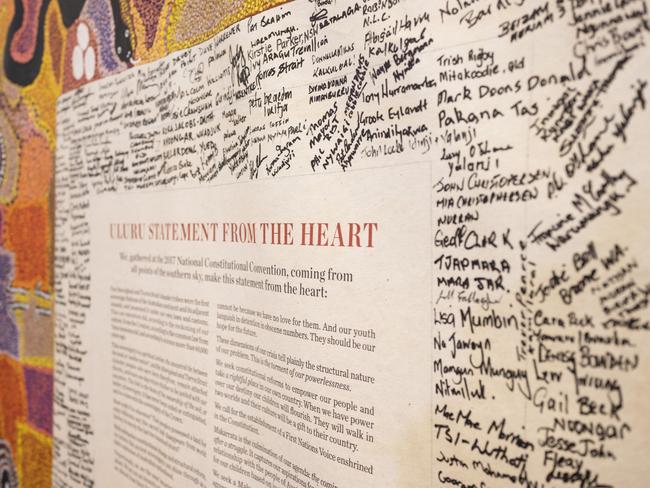

The Voice to Parliament emerged in 2017 from the First Nations National Constitutional Convention and its Uluru Statement from the Heart.

That statement, in turn, recommended a First Nations advisory body that would give advice to Parliament when debating legislation affecting Indigenous Australians.

The idea seems simple enough, and most Australians agree it’s a good idea.

In July, an Australian Institute poll found 65 per cent of voters would vote yes to enshrine a Voice in the Australian Constitution.

Many people I’ve spoken to believe a majority yes vote is inevitable, driven by common sense and goodwill alone.

In fact, in 1967, the last Indigenous referendum – to allow the Commonwealth to legislate on Indigenous issues (no, it didn’t grant Aborigines the vote or citizenship) – almost 91 per cent of Australians embraced reform.

But, despite recent polling, there are a number of reasons why a Voice referendum could yet fail.

The first is Australians’ longstanding resistance to constitutional reform.

Over the past 122 years, we’ve been asked to approve 44 changes to the Constitution.

Of those, just eight have been approved – a natural conservatism not helped by the so-called “double majority” requirement demanding a majority of voters in a majority of states, and a majority of voters overall.

In fact, it’s been 45 years since the last successful referendums that included the mandatory retirement of High Court judges at age 70.

But the most pressing reason is undoubtedly the “material” political climate in which we now live.

With inflation and interest rates overtaking wages and draining our savings – when millions of Australians are struggling to pay power bills and buy Christmas gifts – many on Struggle Street simply cannot afford to think about “post-material” issues such as climate change and a Voice.

In fact, many voters will be hostile towards an Albanese government appearing to prioritise social issues over financial security.

Third, referendums have a much better chance of success if both Labor and the Coalition support them.

Even commonsense questions can fail when one side objects.

In 1988, for example, the innocuous “fair elections” referendum failed after the Hawke government asked us to outlaw electoral malapportionment – an unfair advantage created by too many small seats – in Queensland and Western Australia.

When the federal Liberals warned us it was just a Labor trick (despite the Queensland Liberals supporting the reform), the referendum was doomed and Australians, ludicrously, voted against “fair elections”.

Fourth, the Coalition raises a fair point in arguing Voice proponents have put the reform cart before the referendum horse.

Unlike most referendums where the details of a much-needed reform circulate widely in the community long before the poll, this referendum has seen much excitement among senior politicians but very little detail – and even less enthusiasm – at the grass roots.

Australians will vote against any policy they do not understand.

This leads to a fifth reason: fears among naysayers that a Voice could easily become a third chamber of Parliament or, at least, a powerful gatekeeper with the power of veto over parliament.

Despite legal advice such power could never arise, ill-founded fears alone could be enough to sink this referendum.

Moreover, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s announcement that tradition will be ditched for this referendum – the government will not sponsor official yes and no cases via television adverts and pamphlets – will also raise suspicions the government is trying to pull a fast one.

Anecdotally, the Voice’s permanency is also worrying voters.

Once enshrined, the Voice – no matter how well or how poorly it performs – can never be removed from the Constitution, except via another referendum.

Moreover, other minority groups – from immigrants to the LGBTQIA+ community – might think it unfair their advice is not similarly sought when parliamentary Bills are drafted.

Last, there’s the fact First Nations representatives, as you would expect, are themselves divided over the value of a Voice.

Northern Territory CLP senator Jacinta Price, for example, is vehemently opposed, and even Victorian Greens senator Lidia Thorpe once labelled the proposal a “waste” of money and instead argued for a treaty.

My advice to the Albanese government is unvarnished.

Australia cannot afford to see this referendum fail.

If it does, it will be decades before a Voice will be revisited.

Spend the remainder of this term addressing Voice fears, and defer this much-needed reform to the next term.

We can’t break this nation’s heart again.

Paul Williams is an associate professor in the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University