Opinion: Coalition only the latest victim of our divorce epidemic

Sussan Ley and David Littleproud are the right people to lead their parties, just not right for each other, writes Paul Williams. VOTE IN OUR POLL

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

After years of a declining divorce rate in Australia, the nation has seen a spike in marital separations in the first few months of this year.

And, with the federal Liberal and National parties this week calling their partnership quits, add another split to the list.

The marriage metaphor is apt. When eminent political scientist Brian Costar, writing of the Coalition, titled his book For Better or For Worse, he crystallised the day-to-day tribulations two very different political parties – not always happily engaged – face in attempting to marry urban and regional partners.

But is the Coalition’s dissolution really a divorce, or merely the fourth trial separation in a 103-year marriage?

The Coalition began in 1922 – just two years after the Country (now National) Party formed – when Nationalist (now Liberal) Party prime minister Billy Hughes needed the iron-clad support of the Country Party to prop up his minority government. It was a successful but hardly loving partnership that endured for 21 years.

But Labor’s landslide victory in 1943 was so enormous it killed not only the United Australia (now Liberal) Party but the Coalition agreement, too. Yet, with Bob Menzies’ formation of the modern Liberal Party in 1944, the Coalition was back before the 1946 election. That began a golden quarter-century – where Liberal prime ministers partnered with strong Country Party leaders like Artie Fadden and Jack McEwen – that birthed a touchstone of faith: that the Coalition is the secret to conservative success. Little wonder former prime minister John Howard labelled this week’s split stupid.

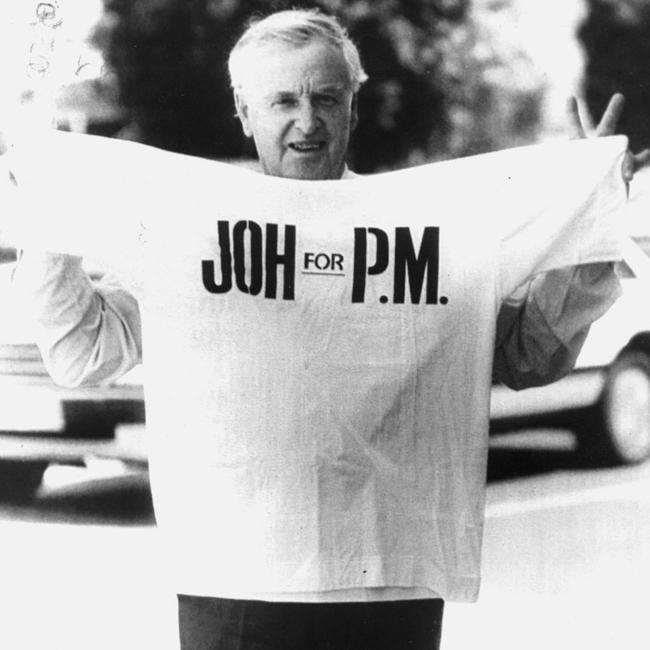

The Coalition dissolved again on Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam’s victory in 1972 before reuniting by the 1974 poll, but collapsed again when Queensland Nationals premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, dissing “lefty” Liberals like Howard, white-anted the federal alliance in 1987 amid delusions of prime ministerial grandeur.

And now Nationals leader David Littleproud, hitherto one of the more reasonable voices in Australia’s most conservative major party, has himself walked away from Australia’s most successful political marriage.

Why? It seems his demands to new Liberal leader Sussan Ley – historically a moderate (but occasionally a conservative) MP who wants to drag the Liberals back to the “sensible centre” – have been rebuffed.

But who can blame her? Ley is right to refuse agreement to long-term policy commitments when the Liberals’ post-mortem election review hasn’t even begun. How can she commit to Littleproud’s nuclear push when it will likely be proven that nukes were pivotal to the Liberals’ collapse?

And how can Ley sign up to a $20bn regional fund, or supermarket divestiture powers, until economic modelling proves such policies plausible?

Most egregiously, how can Ley accept the Nationals’ demand for the right to ignore centuries-old Westminster conventions, and demand the right to speak publicly against shadow cabinet decisions? That is simply unacceptable.

While shocked at the Coalition’s disintegration, we probably shouldn’t be all that surprised. With the Liberals’ worst performance in more than 80 years, it’s only natural that finger-pointing should turn to acrimony, especially with an emboldened National Party – whose primary vote actually increased – decided to flex its muscle.

But that aside, this most recent spat is almost certainly a temporary separation of two ageing lovers desperate for connection because no-one else will have them.

At the very worst, a Coalition agreement will re-emerge after the next election that, should the Libs and Nats compete separately, will guarantee another easy Labor victory.

But common sense will more likely prevail before 2028 as both Littleproud and Ley realise that neither can form majority government without the other and, more pertinently, that Australians never support divided

oppositions.

Even so, each party must make critical reforms before the Australian electorate – now dominated by Gen Y and Gen Z – ever agrees to a conservative agenda.

The first is to pitch to a younger, middle Australia – one ignored by Peter Dutton – interested in personal and national prosperity and not arcane culture wars.

The second is to appeal to women who, in an apparent surprise to

Liberals, demand a closing of the gender gap and family-friendly work environments. At the very least, the Liberals must adopt quotas for women MPs.

Third, conservatives must dump their 1970s “conflict” mindset. This week alone Littleproud said a future coalition should “tear down” a popular Albanese Government, re-elected in a landslide, without offering any reason or alternative. It’s that sort of oafishness that turns off swinging voters.

Ley is the right person to lead the Liberals, and Littleproud to lead the Nats. But, paradoxically, the two leaders are not right for each other.

Paul Williams is an associate professor at Griffith University