James Campbell: Morrison downfall just a taste of personal politics to come

Voters have revealed why Scott Morrison turned them off at this year’s federal election and it’s a sign that politics is about to get far more personal.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

About halfway through the Australian National University’s analysis of the federal election, there’s a stark graph which explains, better than words ever could, why the previous government lost.

The report, released last week, which has been a fixture of Australian political life for nerds of all persuasions since 1987, is the result of a survey of voters aimed at finding out how different groups voted and why.

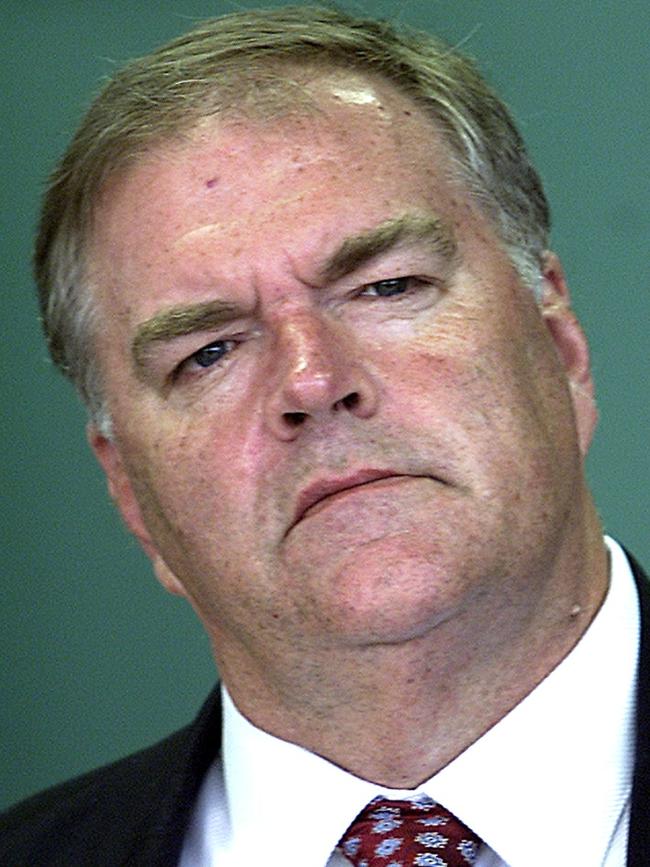

Among the things tracked is voters’ attitudes to the major parties’ leaders and, if the survey is correct, Scott Morrison was a standout: The most unpopular man – or woman – in the 35 years the survey has been running.

Using a scale of 0-10 where zero is hate-their-guts and 10 is let’s-get-a-room, poor old Morrison scored an average of 3.8, just below Andrew Peacock in 1990 with 3.9, Bill Shorten (4) in 2019 and the Ruddster with 4.1 in 2013.

Compared to that lot, at his only outing in 2004, Mark Latham was a rock-star with a break-even 5.

The most popular leader since the survey was ‘Kevin 07’ model Rudd who got 6.1 which was miles ahead of Albo’s 5.3 this May, a number which was only a smidgen higher than the 5.1 Morrison received at his first outing in 2019.

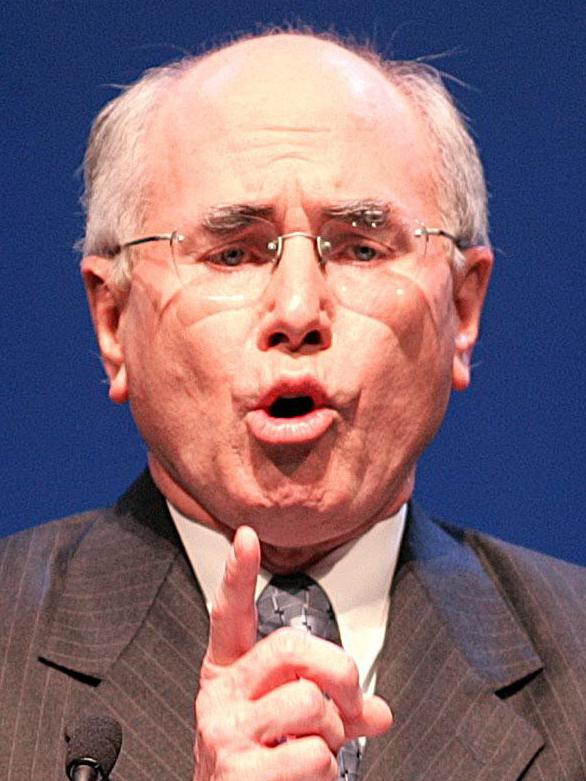

Now, while having a more popular leader than your opponents isn’t always a guarantor of victory – Kim Beazley was more popular than John Howard in 1998 but Howard still scraped home despite losing the two-party preferred vote – it was pretty clear by May the Coalition hadn’t a prayer with Morrison at the helm.

Certainly that’s the conclusion of Labor’s election review, also released last week, which found the most significant cause of the result was “the unpopularity of Scott Morrison and his government”.

If this is true – and there’s no reason to believe otherwise – it raises the question of why? Why was it that by the time we voted this year, Morrison had become so unpopular? How did that happen?

If you wanted to you could attribute his fall entirely to mistakes made by him, starting with the secret holiday in Hawaii, continuing through to the disastrous “I don’t hold a hose, mate” interview rolling on to the claim the vaccine rollout was “not a race”. All of these were real screw-ups, no doubt about it.

But, to my mind anyway, it seemed that it didn’t really matter what he did – the man could do no right.

Take his response to the Women’s March for Justice which, according to the ALP’s review, “demonstrated and catalysed discontent with the Morrison government amongst women across the country”.

Speaking to parliament about the march, Morrison said: “Not far from here, such marches, even now, are being met with bullets, but not here in this country”, adding “this is a triumph of democracy when we see these things take place”.

This statement, the ALP’s review says, “was interpreted as meaning that the women at the rally were lucky they were not being shot”.

There’s no doubt this is true – it was interpreted that way.

But the view of Morrison government insiders is these interpretations didn’t just bubble up spontaneously, they were almost certainly seeded into social media by Labor and its proxies.

According to one insider, the pattern was repeated many times over the term of the last parliament.

“Scott would say something and within hours 20 social media accounts would start pouring out shit about it, then journalists would jump on it, writing ‘Twitter says’,” the insider says.

Sour grapes? Maybe. The big mistakes were, after all, real mistakes.

But even so it’s hard in retrospect not to ponder how many of Morrison’s “empathy failures” were real and how many were astro-turfed.

Ah, well that’s politics. If that’s what they did, there’s no doubt it worked because as the ANU’s survey notes, in passing, that while a majority of voters (53 per cent) said they cast their ballots based on policy issues, this was “down from 66 per cent in 2019”.

You could argue that it was ever thus – unpopular leaders don’t win elections. Except, to note again, that since 1987 no leader has been as unpopular as Scott Morrison and that could suggest the vehemence of that unpopularity is tied to the decline in the number of people who identify with a particular party.

In other words, even as recently as 2004 when the ALP was proposing to make the wildly un-prime ministerial Latham our nation’s leader, there were many more Labor people who were prepared to take their party’s guy on trust.

Almost 20 years later, so many of us are less attached to one side.

According to the ANU, in 2022 just 58 per cent of voters “considered themselves to be close to one or other of the major parties” and almost one in four said they had “no partisanship” – the highest figure yet.

If people aren’t voting on party affiliation or policy, they’re more likely to be voting on perceptions of the leaders. Expect politics to get much, much, more personal. I suspect what happened to Morrison is just a taste of things to come.

Originally published as James Campbell: Morrison downfall just a taste of personal politics to come