Lucy Carne: Celebrating beauty can be empowering for women

Beauty pageants are back, along with the patronising criticism of a woman’s desire to good look, writes Lucy Carne.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

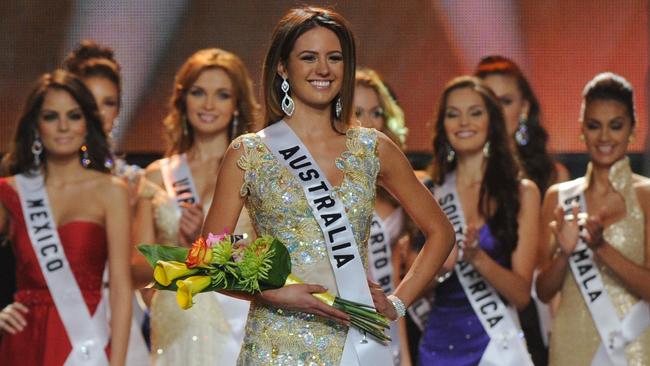

The hair extensions are curled, the fake tan sprayed thick and the lips glossed – beauty pageants are back. The world is finally returning to normal.

Having paused for 12 months due to the global pandemic, the sequined spectacles have sashayed back into the spotlight.

State finals are currently underway for the Miss World Australia competition, which will hold its crowning ceremony on July 9, while the Miss Australia Pageant had its national final on Saturday on the Gold Coast.

The Miss Universe pageant takes place on Sunday in Florida, with Maria Thattil, a 28-year-old psychology graduate who also has a masters in human resources, representing Australia.

Judging by the force of the pageant revival, it seems they’re not fading into insignificance any time soon.

It’s a disconcerting development for feminists and the moral and religious crusaders who deem pageants to be nothing more than degrading meat markets that pit women against each other in a Hunger Games-esque battle of the babes.

Even TV host Karl Stefanovic sarcastically poked fun at Miss Universe, a 68-year-old event watched by over 500 million viewers globally.

He questioned the relevance of the pageant during an interview with Thattil on the Today show last month, raising the argument that beauty contests are considered to be “outdated” and “sexist”.

“What a load of rubbish,” Stefanovic responded, when Thattil said the entrants “deserve to be there”.

Thattil, who was raised in Melbourne by Indian immigrant parents, hit back: “Thank God you’re not representing Australia and it’s me … Think about the fact I’ve been on national television talking about racism, challenging what it means to be Australian, diversity and inclusion. Had I not done something like this, I wouldn’t have the platform.”

And this is exactly where the problem lies with criticising pageants.

Objecting to objectification is easy from a position of white, educated privilege. But for many women, pageants provide not just a platform to launch themselves as a brand (Jen Hawkins, Rachael Finch, Jesinta Campbell), it’s also a way to escape a lack of opportunity.

When Miss World Australia and Miss America removed the swimsuit sections in response to critics, it was deemed a win for the #MeToo movement. But it’s also a troubling example of how the overreach of political correctness can deny women’s rights, especially when it’s still fine for men to strut in slivers of Lycra in bodybuilding competitions.

Banning swimsuits is also essentially sending the age-old message that women are not allowed to be proud of their bodies.

But the enraged dissenters screeching that swimsuit judging sexualises women have clearly never been on Instagram, which we can thank for the disturbing trend of bikini bottoms wedged up bum cracks.

Women who enter beauty pageants are also patronisingly deemed to be deluded and naive simpletons, as though being confident with who they are is a flaw.

This feminist narrative that women must be de facto victims in perpetual pain needs to stop. “It doesn’t matter who you are, what your life is, your situation, who you surround yourself with, how strong you are, how smart you are,” singer Billie Eilish says in Vogue. “You can always be taken advantage of.”

Even June’s never-ending suffering in The Handmaid’s Tale is tiring (truthfully, we’d all prefer to see her have more consensual romps with the hot driver).

Sure, beauty competitions may not fit with modern demands of political correctness, but our view of them is just as anachronistic.

Is strutting a stage in a satin frock really so destructive when we now live in an age where, depressingly, teens post sex videos of themselves on PornHub?

Is it really that demeaning to hand out awards to smart and socially aware women, who also happen to be pretty, when every kid growing up these days gets a prize just for turning up?

Is it so wrong to reward the physical presentation of contestants when that is the exact basis of every dating app?

Face it, we live in a society where beauty is judged.

Even newborn babies prefer to look at good-looking people, according to research by the University of Exeter.

“Attractiveness is not in the eye of the beholder, it’s innate to a newborn infant,” the study’s author Alan Slater said.

Yet, somehow we’ve become ashamed of wanting to look nice.

Misogyny parading as a faux-prude movement has declared we cannot praise women for being attractive and smart.

Maybe it’s time feminism ditches the ancient belief that you can’t be intellectual and want to look good.

Because what’s really that wrong with being empowered by a woman’s beauty and intelligence (even if it is in a pair of six-inch stilettos)?