Opinion: Heretics have a role to play in climate change debates

As 17-year-old Greta Thunberg docked in New York this week and began lecturing the United States on the impacts of climate change, I couldn’t help but wonder if climate centrist Freeman Dyson would listen, writes Michael Madigan.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As 17-year-old Greta Thunberg docked in New York this week and began lecturing the United States on the impacts of climate change, I couldn’t help but wonder if Freeman Dyson was listening.

“Listen to the science!’’ Greta urged President Donald Trump while much of the media nodded approvingly as the Swedish student activist prepared to lecture Americans on the urgent need to curb carbon emissions.

About 100km from Manhattan at Princeton University one of the 20th Century’s greatest scientific minds, Freeman Dyson, was probably nodding his head in agreement.

The English born Freeman, 96 in December, has not merely listened to science but devoted his life to it.

He knew Albert Einstein and has specialised in a wide variety of fields paying particular attention to physics, nuclear engineering and quantum electrodynamics.

Like Greta and most of the educated world who don’t necessarily have tertiary qualifications in climate science or meteorology, he believes global warming is caused by increased carbon dioxide by burning fossil fuels.

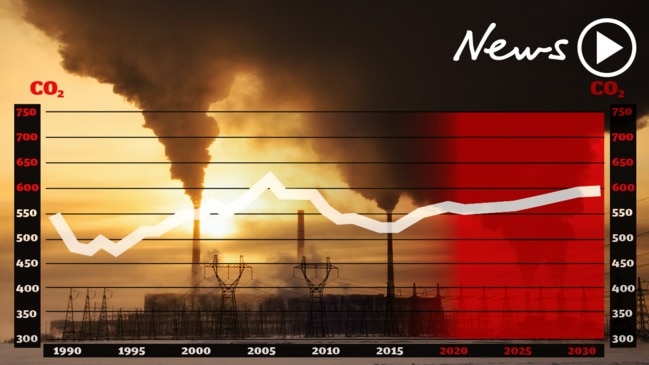

But about a decade ago Freeman began pointing out that the simulation models scientists use to predict climate change impacts have not been carved in stone and brought down from some mountain top.

Freeman, who was actually present when scientific modelling was in its infancy, says the models do a good job of describing the fluid motions of the atmosphere and the oceans.

But they do a very poor job of describing the real world we actually live in _ the clouds, the dust, the pollen in the atmosphere over rural China.

“The real world is muddy and messy and full of things that we do not yet understand,’’ he once wrote.

“It is much easier for a scientist to sit in an air-conditioned building and run computer models than to put on winter clothes and measure what is really happening outside in the swamps and the clouds.’’

The reaction to Freeman’s mild observations over the past decade or so has been extraordinary.

The kinder remarks dismiss one of the few people on the planet who might qualify for the term “genius’’ as a ‘’doddering old fool’’.

Greta, born in 2003 and clearly bright but unable, as yet ,to point to an intellectual achievement which bears her name (such as Dyson’s Transform, a technique in additive number theory) has been greeted not merely as an authority on climate change.

Like the Children of Fatima of the early 20th Century, once promoted globally by the Catholic Church because of their allegedly mystical visions of the future, she’s seen in some quarters as possessing transcendent insights which, if not heeded, will lead to catastrophe.

Greta is right about one thing – we should listen to the science when it come to climate change.

What we shouldn’t do is be swept into an hysterical, cult-like sect which coddles and rewards the faithful, but spurns the heretic who refuses to chant the platitudes.

Freeman appears to me much as a man participating happily in a mainstream Christian Church service but refusing to chant the Nicene Creed simply because he’s studied it, and decided he doesn’t agree with every single word.

The ordinary church goer might find that interesting and even engage him after the service. But the dedicated fundamentalist would sneer and label him a heretic.

In a world which has swapped religion for science, that’s pretty much what he is.

Yet, as Freeman himself points out, there’s always room for the heretic.

He once wrote that politicians and the public now look to science to provide answers to problems and the public prefers listening to scientists who give confident predictions on what will happen as a result of human activities.

“So it happens that the experts who talk publicly about politically contentious questions tend to speak more clearly than they think,’’ Freeman wrote.

“They make confident predictions about the future, and end up believing their own predictions.

“Their predictions become dogmas which they do not question, the public is led to believe that the fashionable scientific dogmas are true, and it may sometimes happen that they are wrong.

“That is why heretics who question the dogmas are needed.’’