Koala habitats destroyed on Qld island under guise of Native Title

Koala habitats on North Stradbroke Island are being destroyed in the mistaken belief by an Indigenous minority they have the right to do so under native title laws, writes Des Houghton.

Des Houghton

Don't miss out on the headlines from Des Houghton. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Koala habitats in pristine bushland on North Stradbroke Island are being destroyed in the mistaken belief by an Indigenous minority they have the right to do so under native title laws.

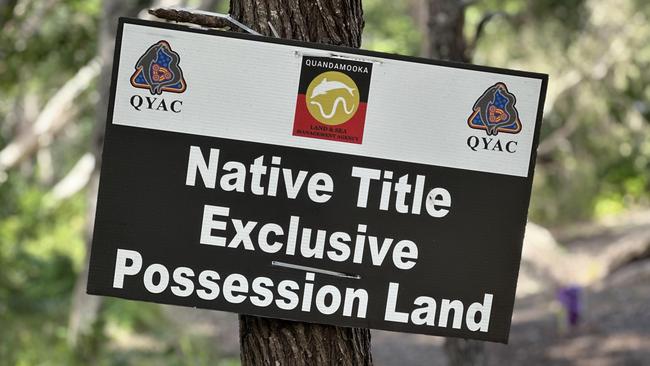

Redland City Council believes more than 90 blocks have been cleared by Indigenous families who have claimed them as their own – often erecting signs to say so. The families plan to build on land they do not own. Some have already established makeshift camps.

White homeowners and many Indigenous islanders say clearing the land was wrong and was done without council approval.

Court documents show Quandamooka people won non-exclusive native title rights over 2,264ha of the island in 2011. Council lawyers told the court that did not imply outright ownership.

Ancient trees felled on native title land have already been cut at the Amity Point sawmill for timber to build homes on land they did not buy and do not own, said David Gray, an influential local.

“I’m livid,” he said.

We visited around a dozen sites where people were already living off the grid in clusters of makeshift homes and tents.

Gray said many of his Indigenous friends were just as appalled as the white community.

“They are wrecking land with high ecological values, yet the council and the State Government is turning a blind eye,” said Gray, an electrician, a professional beekeeper, a round-the-world yachtsman and a former middleweight boxing champion with an MBA.

“They are not being called to account, and I do not know why that is happening.”

Member of Oodgeroo Amanda Stoker, the former senator, said land clearing has accelerated since the Darren Burns court saga.

Burns, an Aboriginal elder, was fined $20,000 by Redland City Council for unlawfully clearing land only to have the decision overturned in the District Court, the Courier-Mail reported.

Judge Bernard Porter said the council failed to prove Burns did not honestly believe he had a right to clear his land.

Burns’ desire to clear the land and build a house for his daughter “was done in the exercise of an honest claim of right” under the state’s criminal code. The defence of acting in relation to property when a person honestly believes they have a right to act was enshrined in Queensland law 126 years ago, The Courier-Mail reported.

The judge said even though the clearing of 2900sq m of high value and “protected vegetation” at Point Lookout was illegal, he accepted the defence that Burns was “not criminally responsible”.

Stoker found the decision “puzzling”. She speaks with authority as a first-class honours lawyer who worked with Minter Ellison and as a Crown prosecutor after working as High Court judge Ian Callinan’s associate.

“Redland City Council sought to prosecute him for a breach of the laws relating to planning because he didn’t seek permission,” Stoker said.

“There are good reasons for those laws. If you don’t go through the proper planning process you end up with houses that aren’t connected to electricity, that don’t have proper sanitation, that don’t pay rates and can’t be found in an emergency.

“During Cyclone Alfred it was quite an exercise to find people living in the bush because they were not, so to speak, on the map.

“There are serious health, safety and living standards implications for people who don’t want to go through the planning regime.

“The court held at trial there had been illegal land clearing and that it was a criminal offence and that a penalty applied.’’

Darren Burns was described in court as the land and sea manager with QYAC, the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation.

“The decision we got from the District Court is a real puzzle. It said the land clearing was held by the court to be illegal, definitely illegal. It was held not to be authorised,” Stoker says.

“Nevertheless, the District Court judge found there was an honest claim of right that meant, in practical terms, there were no consequences for a native title holder to engage in this behaviour.

“What that means is that even though it is illegal, a green light has been sent to people who want to engage in this kind of behaviour. No consequences flow.

“That is causing massive problems for other property holders, and it will in time cause massive problems for the living standards of Indigenous people who end up living on these properties.”

A worrying precedent was set.

“Wherever there is a native title determination, there is now a very real risk this precedent could be applied statewide.

“If that occurred there would be significant impacts to private property rights.”

Stoker has fielded many complaints.

She said native title did not mean Indigenous had exclusive rights to an area.

“It is meant to be land that is shared by all,” she said.

“It’s not for exclusive use by anyone, yet land gets cleared and a sign gets put up saying “this belongs to” with the name of an individual.”

What’s next?

“A modular home will get popped in any day now and it will have no sewerage connection, no electricity and no garbage service. And because they are not paying rates because they are not on the council map.”

Residents feared the arrival of noisy power generators.

“Because of this judgement we now have the unhappy situation that when it comes to land clearing there is one law that applies to native title holders and another entirely to the rest of the population,” Stoker says.

“When the planning regime is subverted, all of the efforts that are made to ensure that buildings that are not destroying pristine habitat are getting ignored.

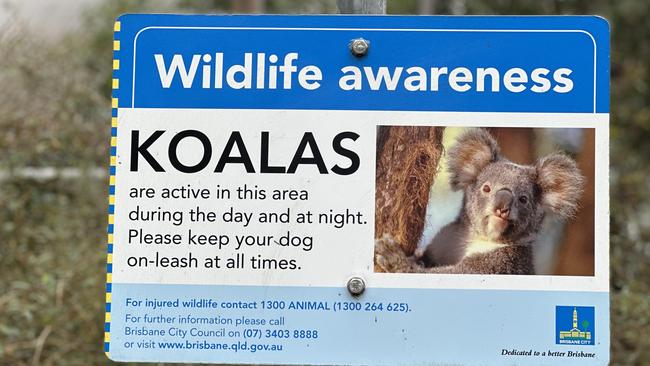

“I’ve seen absolutely priceless, pristine koala habitats destroyed without care in illegal land clearing. You can’t get that back. “These are trees that are hundreds of years old.”

“Clearing has escalated since the judgement. Residents are frightened.”

She said the council “did everything right”.

“The defence was that he had ‘an honest claim of right’ was never meant to power a situation where we have one law applying differently to Australians on the basis of race.”

David Gray agrees: “The court case has empowered some First Nations people to walk onto the bush and cordon off a section of ground and start to build some sort of dwelling there.”

“There are a group of Aboriginal elders who, thank goodness, have been monitoring what has been going on since 2011 and they oppose land clearing.”

He said this group tried to seek an audience with ministers in the previous Labor government. “But they were turned away,” he said.

FLYING FLAG FOR RIGHTS

I arrived by boat to North Stradbroke Island at Dunwich and was surprised to be greeted by a Palestinian flag on Ballow Rdnot far from the jetty. On a second flagpole beside it, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait flags were flying high. Not an Australian flag to be seen in this extraordinarily beautiful chunk of paradise which archaeologists say has been home to Quandamooka people for 21,000 years.

I came to see for myself the unlawfully cleared land, and to ask the Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation, QYAC, how it reconciles its mantra of “caring for country” with the chopping down of old trees.

QYAC is the registered body corporate that manages what it says is the “estate”.

QYAC declined invitations to comment, but its mission statement gives a clue as to why no Australian flag flies there.

“Quandamooka People have never ceded sovereignty of their Country and this issue remains live for Quandamooka People. “Quandamooka People continue to operate under their own distinct system of laws and customs.”

It says native title rights grant exclusive rights to possess, occupy, use and enjoy 2,264ha of land “to the exclusion ofall others”. Furthermore, it says it has “non-exclusive native title onshore rights” over an additional 22,639ha.