Ode of mystery still shrouds the gruesome death of Ludwig von Beethoven

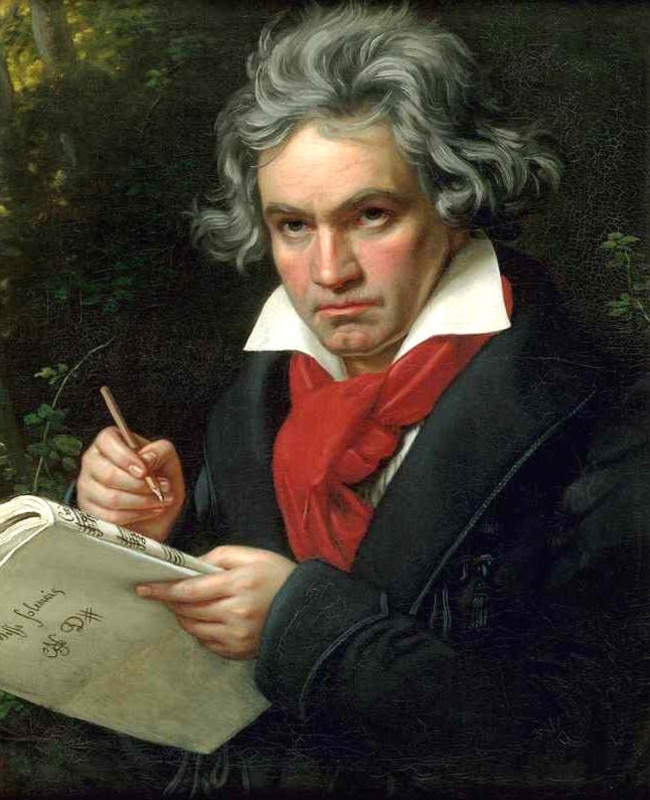

ALREADY deaf when afflicted by extremely bad breath, chronic, foul body odours and painful colic from his grossly distended belly, little wonder German composer Ludwig von Beethoven died a grumpy man.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ALREADY deaf when afflicted by extremely bad breath, chronic, foul body odours and painful colic from his grossly distended belly, punctured to release 20 litres of pussy fluid, little wonder Ludwig von Beethoven died a grumpy man.

The autopsy explanation after his death on a stormy evening in March 26, 1827, was dropsy caused by liver cirrhosis, attributed to his fondness for fortified wine every evening.

A post mortem also revealed Beethoven suffered atrophy of the brain, fibrotic liver riddled with beanlike nodules, enlarged pancreas and abnormal kidneys. Medical speculation about what killed him began after his burial, with alternative explanations ranging from syphilis, infectious hepatitis and lead poisoning to sarcoidosis inflammation and Whipple disease, a rare bacterial infection often affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Given treatments afforded the composer for his ailments in the months before his death, all explanations were a possibility. Born in Bonn on or near December 16, 1770, Beethoven’s suffering began when his father Johann, a court singer, began teaching him to play the violin and clavier, which he reached by standing on a footstool.

Neighbours reported the small boy wept during clavier lessons, when his father beat him for hesitation or mistakes. They claim Beethoven, whose grandfather and namesake was Bonn’s most prosperous and eminent musician, was flogged daily, locked in the cellar and deprived of sleep for hours of practice.

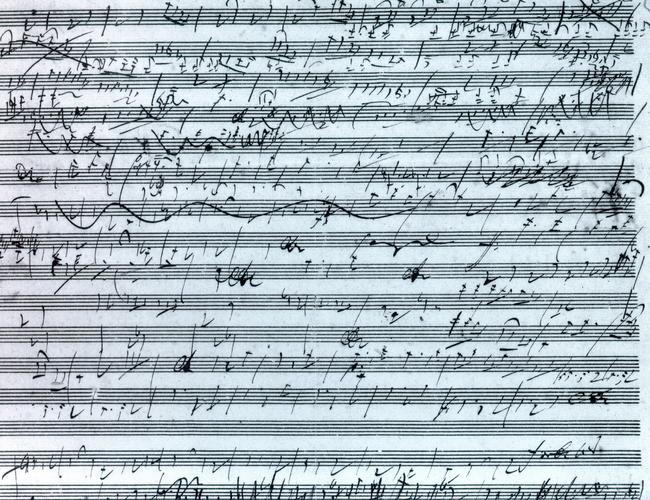

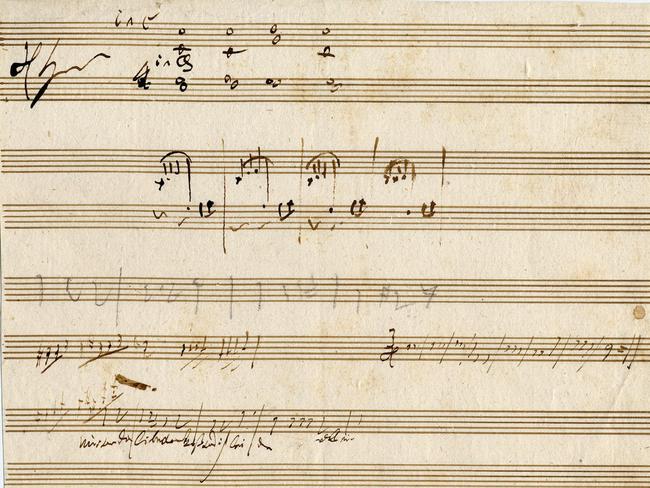

Despite beatings later dismissed as exaggerated, Beethoven quickly proved a prodigiously talented musician. Although he began going deaf by his late 20s, in his 56 years he composed nine symphonies, 17 string, five piano and one violin concerto, 32 piano sonatas and one opera.

Brain trauma from frequent falls or other physical abuse by his father was suggested as the cause of his deafness, posthumously attributed to Paget’s disease. At his autopsy an alternative diagnosis of neurosyphilis was discounted.

“My hearing has become weaker during the last three years,” Beethoven wrote in a dairy entry in 1801, explaining that despite prescribed strengthening medicines and oil of almonds, “my hearing became worse and worse. Then an Asinus of a doctor advised cold baths, a more skilful one, the usual tepid Danube baths. These worked wonders; but my deafness remained or became worse. This winter I was truly miserable; I had terrible attacks of Kolik.”

Abdominal disorders dated to 1792, when he moved to Vienna and began complaining of recurrent pains and diarrhoea. Friends reported he suffered a severe fever, possibly typhus, in 1797. Between 1812 and 1820, as he repeatedly complained of colic, diarrhoea, anorexia and dehydration, he turned to alcohol to kill the pain, but later found alcohol worsened his abdominal discomfort.

As he began a bitter battle with his widowed sister-in-law Johanna in 1815 for custody of her son and his only nephew Karl, then nine, Beethoven became totally deaf. Winning custody of Karl in 1820, he then forbade him to see his “immoral” mother, and suffered a prolonged attack of jaundice.

Karl frequently ran away to his mother, but Beethoven once called police to have him forcibly returned. And while Beethoven completed his Ninth and final symphony, with its famed choral finale Ode to Joy in 1824, Karl had become a young “rake” acquainted with every Viennese woman of ill repute, and suspected of punching his foster-father in one of their regular arguments.

As Beethoven battled financial crises to preserve a financial legacy for Karl, his nephew threatened suicide. Karl shot himself in late July 1826 at one of Beethoven’s favourite retreats, the Rauhenstein ruins in the Vienna woods. Although Karl survived, Beethoven was shocked and appalled, as suicide was then a crime subject to a police inquiry.

Beethoven implored Johann, his only surviving brother and prosperous from army contracts, to will property to Karl. When Johann refused.

After a heated quarrel in December 1826 Beethoven stormed from his brother’s country house. Johann would not lend a closed coach and Beethoven, taking Karl with him, refused to wait for a carriage, instead travelling in an open wagon in freezing weather. Reaching Vienna a day later, Beethoven came down with pneumonia, worsening his jaundice.

As Beethoven’s skin turned yellow and his stomach bloated from “dropsy”, or oedema, on New Year 1827 he again quarrelled with Karl, who wanted to join the army.

Beethoven’s belly was “tapped” by surgical incision to insert a glass tube, without anaesthetic, at least four times between December 20, 1826 and February 27, 1827, removing more than 20 litres of fluid per session.

When he died friends removed a sample of his hair, while his body was exhumed to take skull samples in 1863.

Hair analysis in 2005 revealed high lead levels, leading to speculation that lead in cheap wine caused his mood swings and death. But analysis at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in 2010 found lead in his bone samples were no higher than normal for a man his age.

Originally published as Ode of mystery still shrouds the gruesome death of Ludwig von Beethoven