Ocean swimmers put risk into perspective after first shark attack death in 60 years in Sydney

Overcoming fear after a fatal attack is ‘just part of the package’ according to those who went straight back into the ocean this week.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

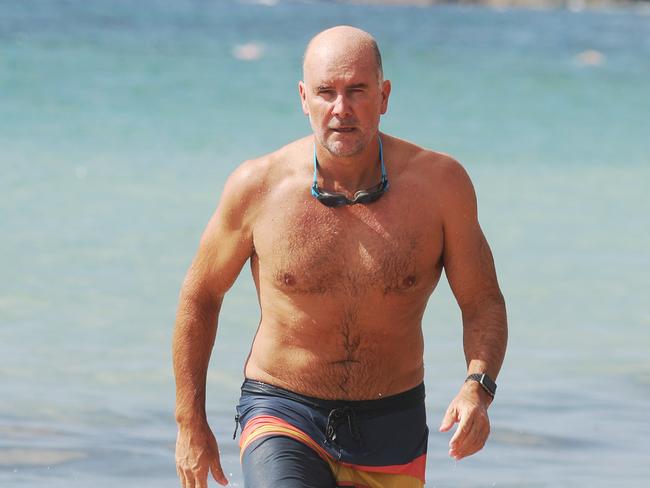

Dr Darren Saunders knows the mind game it takes to enter the ocean after a fellow swimmer is attacked by a shark. And despite seeing a shark during his regular swim on Wednesday, and news a swimmer was killed by a great white the same day, the cancer biologist was quick to get back in the water.

“It is kind of like a mental discipline to overcome the fear and tell yourself the risk is so small, I’m going to swim through it,” said Dr Saunders, who went for his usual ocean swim at Malabar on Thursday, the day after Simon Nellist was killed one bay over.

“You tell yourself it is an irrational fear and you get on with it and that is part of the package.”

Ocean swimmers dive in every day having mulled over the risks, although suppressing the fear becomes more challenging after news a fellow swimmer has been killed by a

great white.

Authorities are still searching for the shark which killed Nellist, 35 off rocks near Buchan Point at Little Bay on Wednesday afternoon.

The attack on Nellist was the first fatal shark attack in Sydney since 1963 (scroll down for history of Sydney shark attacks).

Dr Saunders has seen plenty of sharks, and is not deterred because he looks at the world through risk.

“I swim at Malabar, Coogee and Maroubra, I’ll swim out to Wedding Cake Island off Coogee. I saw a shark on Wednesday, it was only five foot (1.5m), but you see them quite often,” the 50-year-old father-of-two said.

“The risk of a fatal shark attack is like over one in a million, but it’s tiny, it’s so small. You have more chance getting yourself injured actually getting to the beach than you have getting injured at the beach, that is the way I rationalise it,” he said.

Already this year, 46 people have died in car accidents in NSW, but no one avoids getting into a car.

“There are things we all do every day of the week that have more risk than the things we obsess over. Having said that you try to be sensible, you don’t swim at dusk and dawn when sharks are more actively feeding apparently. If there are lots of fish in the water you don’t go swimming around big schools of fish because you might run into a shark. You can minimise the risk,” Dr Saunders said.

“I ride my bike, cycle a lot and I have much more chance of being whacked by a car while cycling than being whacked by a shark while swimming.

“Just a few weeks ago I was surfing and a shark went by me in a wave, and it got into my head so I got out as I was not comfortable.

“The sharks are there, you take it for granted sharks are there. I’m a surf lifesaver as well and sharks are always spotted (but) it is very rare when humans have a close-up encounter.

“I’m not minimising anything to do with the fact someone just got killed, but I am about to go for a swim now,” he said on Friday.

Anxiety expert Associate Professor Melissa Norberg said fear around ocean swimming and the brain’s “fight or flight” response could leave beaches sparsely populated for some weeks as people come to terms with this week’s fatal attack.

The National President of the Australian Association for Cognitive and Behaviour Therapy said it’s not surprising the event has left many people avoiding the waters.

“We learn to fear things, either because something tragic has happened to us or we’ve seen it happen to other people or we or people have told us about it,” she said.

“So although it’s been 60 years in Sydney since we’ve had a fatal shark attack because it’s just happened, that’s what we’re using to assess whether swimming is safe or not.”

She said the amygdala, or fight or flight centre of the brain, could lead to some people over-estimating the risk of a shark attack and avoiding the water in the short-term. Once some time has passed without an attack, she says most people will return to the water.

“I think what we’ll see is that most people will go back because they’ll realise you know, I’ve been coming to the beach regularly for 20, 30, 40 years, and it’s been safe. ”

Some individuals may, however, not adapt, especially if they already had existing fears about sharks, she said.

If that is the case, psychotherapy is recommended.

Gradually exposing yourself to the feared event, for example, swimming and assessing the facts of the situation are useful ways to push through the brain’s fear response, she said.

“I think it’s important to assess the reality of the situation. Fear is a healthy response,” she said.

“It keeps us alive, but sometimes we experience it when we don’t have to so we always need to figure out when we’re fearful of situations if there is a real life threatening situation or if it’s something that’s actually not that bad.”

Bondi local Leon Goltsman, who has been swimming along the eastern beaches for decades and has been a surf lifesaver since he was 17, said rational thinking mixed with realistic caution shapes his decision to keep on swimming.

The eastern suburbs councillor said Little Bay, which is among his favourite swimming spots, was known to be an area for sharks in certain conditions.

“There are always a lot of people swimming there but what made it different (on Wednesday) is the conditions,” he said.

“I wouldn’t go swimming there if it was rough, there were seagulls or bait in the water because there’s no guarantee.

“I’d go back for sure but I just want to make sure that I practise caution like I’ve always done.

“I think a lot of people will still go back. I hope they don’t now think there is all these sharks in the area because nothing has changed, they’re still in their natural habitat and people just need to be more mindful.

“I still don’t fear sharks, I fear traffic more.

“If you simulate what a shark sees it is very hard to distinguish between them, the prevailing thinking is most encounters between humans and sharks are a case of the shark taking a bite because that is how sharks figure out if there is something tasty to eat,” he said.

Retired Little Bay local Frans Ruisan loves the salt water and his daily swim routine so much he won’t be deterred even for a second.

“I have always thought it was quite safe swimming down here because it’s protected and I come and swim here every day when the sun is out,” he said.

“The reason I swim here is it isn’t big and open like Bondi or Maroubra, down here I always thought it was quite safe, being protected by the rocks.

“I’ve been swimming here for 40 years and I’ve never seen a shark here.

“I will definitely keep swimming. The shark doesn’t worry me because I think the salt water is everything. I’ve never been afraid of sharks here.”

Among those who were quick to venture back into the surf after the fatal attack on Simon Nellist were swimming group Bondi Salties, which held a group swim from north to south Bondi just after 6am on Friday.

The Salties then observed a minute’s silence in the waves in honour of Nellist, who was an experienced swimmer and scuba diver.

SYDNEY’S BLOODY SHARK ATTACK HISTORY

The horrific shark attack off Little Bay on Wednesday afternoon was the first fatality in Sydney since 1963. But that remarkable 59-year fatality-free period disguises Sydney’s bloody history of deadly shark attacks.

There have been hundreds of shark attacks in NSW since records began, but of the 101 fatalities recorded since 1791, 61 happened in and around Sydney. The great majority happened before meshing began in the 1930s.

According to the Global Shark Attack file which cross matches newspaper articles with police, media and coroner’s reports, the first recorded attack in Australia in the file was in 1791. “Female, Australian Aboriginal, bitten in two” in Port Jackson.

As a registered researcher with the Global Shark Attack File (GSAF) Bob Myatt has helped collate Sydney’s history of shark attacks.

“Before meshing there were clusters of attacks on the same beach, one after the other, and quite considerable number of attacks in and around Sydney,” he said.

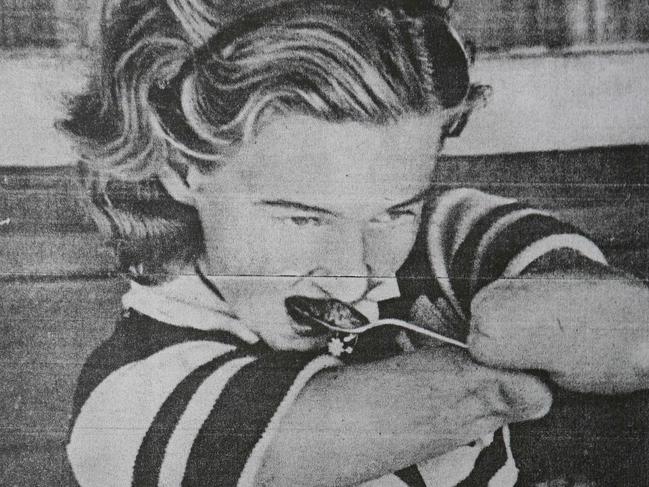

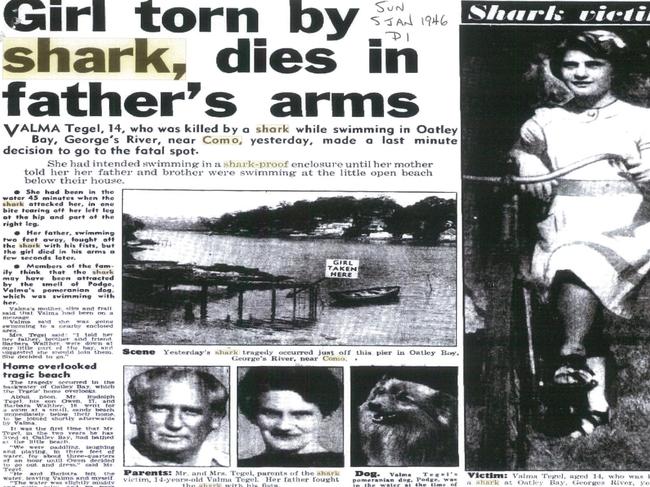

It is hard to fathom the horror our forbearers experienced nearly every summer in Sydney’s beaches and waterways. Take a newspaper article from January 1946 which detailed the fatal shark attack on 14-year-old Valma Tegel at Oatley Bay whose left leg was severed as she played in the Georges River.

“Sydney has had its first shark attack fatality this season, the victim being a girl of 14 who was bathing in shallow water in the Georges River. Shark tragedies are commonest in the summer months,” it read.

The reportage was not sensational, it was the truth, almost every summer someone was fatally attacked. Three people were fatality attacked in Sydney Harbour or estuaries in the 12 months from December 1887 to December 1888; Thomas Cochrane at Ryde estuary, a Mr Ryland, who fell into the river below the Hawkesbury Bridge, and 11-year-old Stephen Carter, who was killed while swimming at Iron Cove.

Two more boys would die in and around Balmain less than a decade later – Thomas Terrill, 14, was attacked while swimming with friends at West Balmain on December 9, 1895. The newspaper reported “a school of monster man-eating sharks was recently driven into Sydney Harbour by storms … the body was hauled into the boat when it was found the shark had bitten away the boy’s entire abdomen and almost severed his body in two.”

The following month, on January 11, 1896, 11-year old William Ready died while swimming with friends at Iron Cove.

In 1902, John Ogier, 31, fell into Kerosene Bay off the river steamer Halcyon and was attacked by a shark. “The back, the spine and pelvis being all that remained,” the newspaper report said at the time.

There were two fatalities in 1903, and another eight fatalities up until 1929, Sydney’s summer of horror.

A suspected rogue shark killed three people in the space of one month. On January 8, 1929, John Gibson, 39, was fatally attacked at Bondi Beach. Four days later 14-year- old Colin Stewart died after another attack also at Bondi.

Stewart was not out too far when the shark lunged at the boy, lacerating his leg from hip to thigh.

A nearby man named Robert Kavanaugh dragged the teen in

from the water but he died at St Vincent’s Hospital 14 hours later from blood loss.

Just 10 days later, on February 18, Allan Bucher, aged 20, was also fatally attacked at Maroubra.

New Year’s Eve in 1934 was the scene of two attacks: 19-year -old Richard Soden was swimming across the George’s River at Moorebank, near Milperra Bridge when he was fatally attacked. Shortly after, at dusk, Bankstown teenager Beryl Morrin, 13, was waist deep washing off mud in the Georges River when a shark grabbed one hand and then the other.

Beryl survived the ordeal despite losing both hands. There had already been three other fatal attacks in NSW in 1934. One at Dee Why in March, one at North Steyne in April and one in Woy Woy earlier in December that year.

Regular attacks continued until public pressure prompted the shark meshing program which was introduced in 1937 along 18 Sydney beaches, extending from Palm Beach to Cronulla.

The last fatality before Wednesday’s was at Sugarloaf Bay, Sydney Harbour, in 1963. On January 25, actor Marcia Hathaway, 32, her fiance Frederick Knight and four friends arrived at Sugarloaf Bay on board a cabin cruiser for a picnic. Marcia was wading waist deep when the shark attacked, almost severing her leg. Knight, who was beside her, fought the shark with his hands and kicked it. The shark having almost torn off her right leg, Marcia was helped ashore but as is the way with many attacks, she died of shock and blood loss some 20 minutes later.

More Coverage

Originally published as Ocean swimmers put risk into perspective after first shark attack death in 60 years in Sydney