The SA shops staying old school in the age of digital

Almost anything can be bought with the click of a mouse in 2019 — but SA Weekend meets four small shop owners who are defying the online revolution with great products and customer service.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Shop trading hours in Adelaide are a mess

- Adelaide supermarket trading laws: Shops cut back hours

- Prizes, discounts, freebies: Check out the latest subscriber rewards

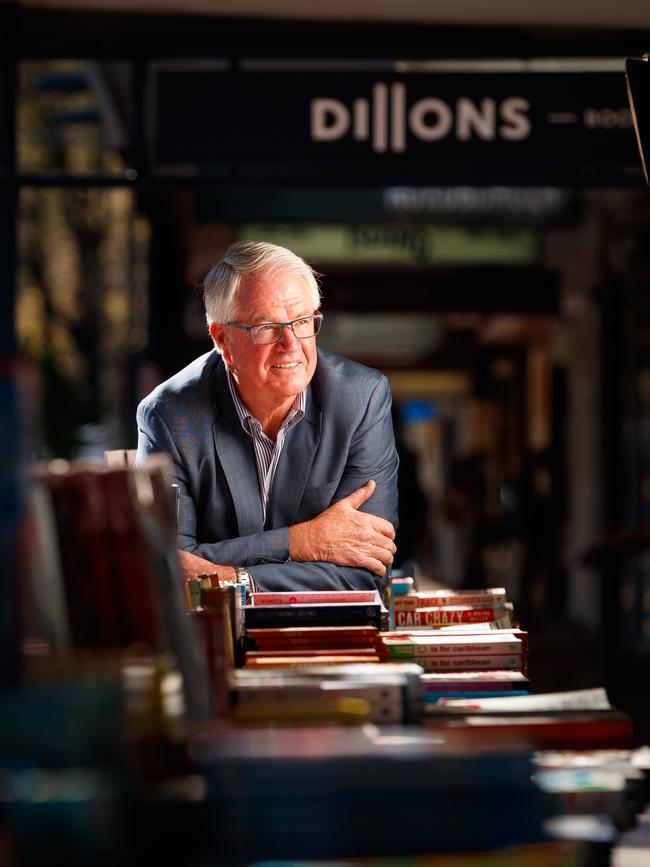

Ross Dillon calls it retail dancing.

The art of staying afloat in a retail environment that has changed beyond all recognition as the internet and the digital revolution changed almost everything about the way we shop and what we buy.

What Ross Dillon sells is books.

A commodity many predicted would fade away as screens and gadgets replaced them. And, for quite a while, the doomsayers looked as if they would be proved correct. Bookshops started to fade away. Big names such as Angus & Robertson and Borders disappeared from our streets. Internet giants such as Amazon and Book Depository were taking over.

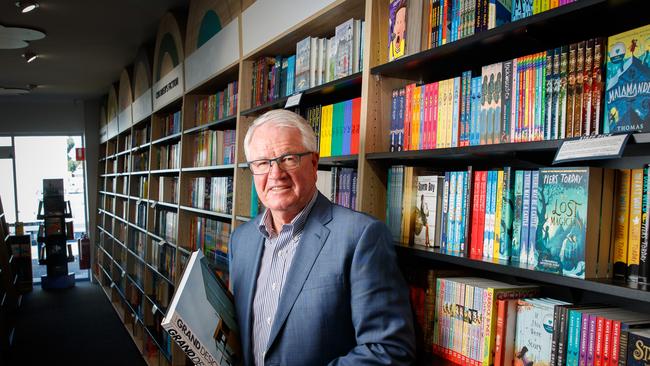

Yet here is Dillon in the middle of his Dillons Bookshop on The Parade at Norwood talking about his latest expansion. It’s his sixth since starting the shop in 1985. Back then the store measured 65 square metres.

Now it covers 700sq m after an $800,000 refit and expansion and carries 30,000 titles.

“I have always believed in spend money to make money,’’ Dillon says. “I call it retail dancing. Changing feet, moving, keeping people interested in you, so you don’t bore them, so they don’t want to walk pass you.’’

The 71-year-old Dillon attached his name to the store in 2011. Before that it had been run as an Angus & Robertson franchise. Dillon believes the demise of Angus & Robertson said more about the company’s management, than any loss of love of books by the reading public.

“They had inexperienced people buying in Angus and Robertson for 100 company stores. They didn’t know what they were buying, they didn’t know what they were stocking,’’ he says.

In contrast, every week Dillon receives a 55-page report detailing every book sold in the last week.

“I go through this printed report line by line which tells me what the sales activities are for this product for the last 10 weeks – has it sold five times a week?

“If I was a professional punter I would want to know what the form of that title is. That flows right across the stock for the whole of the shop.’’

Dillon divulges interesting little details of how bookshops operate. From the outside you would think that the bestsellers – this week’s JK Rowling or Lee Child – would dominate. It turns out 80 per cent of the titles sold in any given week will only sell one copy. Another 10 per cent will sell only two. The other 10 per cent are the bestsellers.

Which is part of the reason behind the expansion. The bigger the range, the more books Dillon sells.

Not that there haven’t been times that he worried about it all. Dillon’s first foray into the world of business, after a stellar football career where he played for Melbourne in the VFL and Norwood in the SANFL, was in 1978 buying a newsagency in Norwood, around the corner from the bookshop. He survived the high interest rates of the 1980s and early 1990s.

“I didn’t know much different, I just thought I’d better pedal faster,’’ he says.

For a while he thought the advent of the e-readers, and devices such as Kindle, would prove an existential threat.

“I could see all this physical stock going. Because that was the way society was going.’’

Dillon says e-readers account for around 15 per cent of the market, but “if anything in the last couple of years there has been a slight decline’’.

However, technology, did lead to the demise of the music and DVD collection that had been a staple of the shop. There was also an ABC section there, but Netflix and streaming services for movies and videos meant that end of the business had been losing money for five years.

“After Netflix it really started to die,’’ he says, “That’s what I thought might happen with books back when e-reading was introduced.’’

Dillon says having good staff is also vital to survive. Having people who can provide the personal touch not possible when buying online.

“Look for lively, driven, warm people who help create an environment so when people come in they feel at home and when they step out the door they want to come back,’’ he says.

Which leads into another reason why Dillon’s has done so well. It’s an integral part of Norwood.

“In book shops they talk about community, they are part of the community. I try and do that as much as possible.’’

TOY STORY

Andrea De Gioia sees the children come into her Port Adelaide toyshop.

Maybe they are eight or 10 years old. She watches them come in to her airy shop with its high ceilings and enormous glass windows and she can tell they’re not expecting too much. Perhaps they are a little resentful at being dragged away from their Playstations or Xboxes to come to this toyshop with its wooden toys and jigsaws and kites. Toys that require a little more effort than just jamming a finger into a joystick. But as they move around the toyshop, De Gioia also notices a change.

“They have, not quite jaded, but sophisticated tastes,’’ she says. “Thinking there will be nothing here for them.

“Then you hear them start saying ‘this is cool, this is interesting’. It’s a matter of putting it in front of them to let them know there is more out there apart from something on a flat screen.’’

De Gioia started Lighthouse Books in Port Adelaide five years ago. She’s had a long love affair with selling toys. She was studying a management degree when she started in the toy department at the old John Martin’s department store in Rundle Mall.

“I had so much fun I stayed until Johnnies closed (in 1998),’’ she says.

De Gioia remained in the retail world. She moved out of toys for a while but came back to work at Windmill in Norwood. For a while she thought it was time to try something new. To get out of the retail world.

“I kept walking past empty shops and doing floor plans in my head,’’ she says. “And I’ve had this idea since my Johnnies days, so it was time to pour it out of my head and into reality and see how it goes.’’

And so Lighthouse Toys opened for business in November 2014.

“It’s a lot of hard work. It’s great, its rewarding. When it’s your own business its blood sweat and tears and you have to do it if you love it.’’

De Gioia chose the Port because she’s always loved the area and the character of its old buildings. The shop she chose had been empty for two years and needed a decent clean to remove the accumulated grime and dust.

But she says it was worth the effort.

“You don’t find this kind of character in modern buildings. It was built for retail from the very start.’’

In a world where toys can be bought cheaply online or in the large department stores, De Gioia brought her own philosophy of toys into play.

“It was much more about the toys being something the child could do something with, rather than the toys do something,’’ she says. “It’s much more about the children engaging and using their brains and developing but having fun. They have to be fun otherwise no one is going to play with them in the first place.’’

The internet is something of a double-edged sword.

“It’s a matter of finding the silver lining I suppose,’’ she says. De Gioia also uses the online world to source toys from all over the globe. A lot of her stock comes from Europe and the US. Her big sellers are wooden toys for very young kids, jigsaws, especially for adults and kites.

The internet had also educated consumers about what they want as well. About which brands are reputable and worthwhile and those that are not. Her customers are also likely to be willing to pay a few more dollars.

“Our customers want quality and people who want quality know there is a different price scale to it, as opposed to someone who wants the cheap knock off and then learns a lesson as to why it’s cheap.’’

Another of De Gioia’s philosophy is to stay away from the fads and the toys that grab children’s attention for a brief amount of time before being discarded. Indeed, she sees her toys becoming family heirlooms.

“They (customers) know they are buying something that will last their child and then get passed on to another child and another child. That’s what we look for. We want things that are built to last.’’

VINYL COUNTDOWN

After a working life dedicated to numbers and management in the relatively tuneless world of computers and IT, Kye Azi retired and turned his lifelong love of music into a business.

“I have always dreamed of being surrounded by records every day,’’ Azi says. “After all I have spent so much time in record shops.’’

Growing up in the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, Azi jokes music was his “refuge’’ as he was the only boy in a gaggle of four children. Then when he moved to the US to study accountancy at the University of Missouri he worked part-time in a record shop.

Because Malaysia was a former British colony his early music loves reflected that history and he was a fan of the country’s post-punk scene which produced acts such as The Police and Gary Numan.

“For a while for me, after The Smiths broke up, music died,’’ he says referring to the famously miserabilist Manchester outfit.

It was four years ago that Azi decided to take the plunge with Holy Vinyl, which sits on Unley Rd in Malvern. Vinyl has been making a slow comeback in recent years after having long ago been replaced first by CDs then devices such as iPods and various streaming services.

He says the number of new vinyl releases sold each year has jumped from 4 million in 2010 to 20 million last year. It’s a good rate of growth but still a long way short of the one billion discs that were sold before the market collapsed.

But it’s impossible to track how many second-hand records are sold.

He talks of his philosophy of the three “Hs”.

“One (H) is the heart, second importance is the hearing. It does sound better. The third is the touch. The hands. For me that is equally as important as listening.’’

Azi believes a second-hand album in good condition still sounds better than a newly pressed reissue.

Azi’s angle on selling was to focus on quality. He thought that was the best way to differentiate himself from competitors and also to provide a service you’re not going to receive when buying online.

“One thing I wanted to do when I was planning for the shop was to address some of the things that I thought should have been better,’’ he says. “Mainly it’s about quality. From the way things are laid out, to the shopping experience. Also quality of the things that are being sold.’’

He says any records over $10 will have been professionally cleaned

“I grade every single thing I have in the shop. That is one thing that differentiates my shop from the rest.’’

Azi knows there are cheaper places to buy records. Azi says he can also offer advice.

He considers himself an expert of different vinyl pressings and is not afraid to tell a customer if a second-hand record will still sound better than a new reissue.

He says running his own business has “been harder work” than he thought. He’s in the shop almost every day. Even on Tuesday, which is supposed to be his day off, he’ll often come in for a few hours. He says he needs to make around $200 a day to cover costs.

“On some days when it’s cold and wet, it’s really quiet and you really get frustrated,’’ he says.

“It’s about managing the cost. I’m not going to get rich from doing this. I can sell so many collectables every day and I still won’t get rich.’’

But there are good days as well. He recently sold an early print of The Beatles’ White album in mint condition for $550 and thinks he undersold it.

Despite all the challenges, Azi is enjoying his new life. He’s rising 60 but in a sense is reliving his youth. Hanging around a record store, listening to music all day long.

“Yeah, yeah I love it,’’ he says.

SAVER OF SOLES

Massimo Sassi has me pegged immediately. I’ve made my way from the front of his small shop in the city to his workplace at the rear. He looks at my feet.

“You’ve never had your shoes repaired have you?’’

I can only confirm the truth of his statement. He doesn’t just mean the pair I’m currently sporting, I take him to mean, that I’ve never had a pair of shoes fixed up.

Sassi runs Classic Shoe Repairs in Grenfell St in the city with his wife Carmel. It’s a longstanding family business. His Italian immigrant parents Renato and Anita bought the shop in 1974 and their son has been working there since 1981.

It’s fair to say he knows his shoes.

I look at my feet. I like my shoes. A pair of tan Wild Rhino boots that were on sale at Myer a few months ago. Sassi notices one of the rubber heels has come off, a detail I hadn’t noticed, and offer to fix them.

I ask if in this day and age, where everything seems so disposable, who still has shoes repaired.

“If you are paying $150 for a pair of shoes you are buying a very cheap pair of shoes that won’t last,’’ he says. “These days you have to spend $250 to $350, $400.’’

And when you are buying in the upper price bracket, it pays to have them repairer. He shows me a pair of well-worn, creased RM Williams’ boots.

“You can spend $150 like this gentleman here. He has $350 to spend elsewhere.’’

But Sassi sees all sorts in his shop. Big jobs and small and he works on anything up to 200 pairs of shoes a week. He shows me a pair of woman’s shoes. They cost her $50 and it will cost her $50 to have them resoled but they don’t make them anymore and they are comfortable.

Sassi doesn’t have a website, although he and son Stefano, are thinking about it. He relies on repeat customers, word of mouth and the location in the middle of the city.

“We survive by the buildings we have around us. They are our providers over the counter,’’ he says.

He says the only technology change over the last 40 years has been the rise of the EFTPOS machine. Even 10 years ago only around 20 per cent of customers paid by card, it’s now around 90 per cent. Which is okay until there is an outage and none of his customers have cash.

Sassi is 60 but thinks he can do another five or 10 years. He still enjoys the work and the interaction with customers. But it’s not easy. He and wife Carmel work six days a week, they don’t take lunch breaks and haven’t had a holiday in 13 years.

But he thinks shops like his are important, not just for him, but for all of us.

“I still think there is future in this,’’ he says. “If you got rid of all the little record stores and all the little type of stores it would be too antiseptic. There would be no flavour.’’

Originally published as The SA shops staying old school in the age of digital