The Missing Australia: Families of Robert Simmons and Terry Lloyd tell of their search for closure

As Australia marks Missing Persons Week, two families reveal their theories about what happened when their relatives disappeared without a trace.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For many years Patricia Simmons looked everywhere for her brother.

The last time she saw Robert Simmons, 22, was in February 1987. It was her wedding day in Melbourne – a day she knew she would never forget, but one she could never have imagined would mark the final time she saw him.

For years and years as she walked through crowds and into shops, she looked closely at each face she passed by. What Simmons was looking for was a reunion – but she was also desperately seeking answers and closure to a mystery that robbed her of a brother and shattered her family.

“I used to see him everywhere I looked. At one point I attended an ashram because someone said he was going to join one, and I was looking at everyone in the building … I scoured the internet and Facebook and wrote to so many people,” she recalls.

Robert’s car was found abandoned in NSW, and his bank account has remained untouched from the time he disappeared. Any hope she had he was alive began to fade in recent years and Simmons started to accept he was likely dead.

But like the thousands of families of long-term missing people in Australia, the not knowing if he was still alive somewhere, and total lack of clarity about his final days, has made life hard.

In Australia, someone who has been missing for more than three months is classified as long-term missing, and there are 2500 of them, according to the federal police.

“On the one hand, I have come to acceptance, but on the other hand, I really want to know what happened,” Simmons says. “What this has done to the family – it has turned people against one another in some ways. Some people want me to look, others want it left alone … it absolutely has had a ripple effect.”

Answers would mean they could not only give Robert a dignified farewell, but finally allow the rest of the family to move on – and stop looking for him.

“If we knew what happened, and we knew for sure, 100 per cent, we could bury him. At the moment, that isn’t what we have.

Instead, the Victorian woman was left to do her own investigative work to try and piece together her brother’s movements. In doing so, she believes she has identified someone who might assist in her quest for closure.

Robert showed up to her wedding with a friend she has since learned was someone he partied with regularly. The pair went to Sydney in February 1987 and at some point returned to Melbourne where they partied at nightclubs and in people’s homes.

Robert went to a party with this friend, but Robert was never seen again after he left the party to buy alcohol or drugs.

Simmons says the friend had given a statement to police at the time to assist them in piecing together what might have happened. The friend is not accused of any wrongdoing.

“Nothing’s come of it really, nothing. But … everything keeps going back to that night. Every time I speak to anyone, that’s where it all goes back to.”

As the months rolled into years and with Robert still unaccounted for, Simmons began asking questions and doing her own investigations.

“I’ve interviewed every one of my brother’s friends,” she says. “I’ve worked out the scenario that’s occurred within a particular few months around the time he went missing. So I kind of know what’s happened. But, I’m not a police officer. I can’t go interviewing people.”

She has given police a DNA sample twice in the hope it could be linked to any remains that are found or to unidentified remains that are being held in labs across the country.

She is frustrated by what she sees as a lack of urgency in dealing with missing persons cases by police. “They have a starting point of, ‘They have gone missing and they’ll turn up.’ And they don’t turn up and they don’t change tack and then start looking at it. That’s how it’s appearing to me anyway.”

IS DAD STILL OUT THERE?

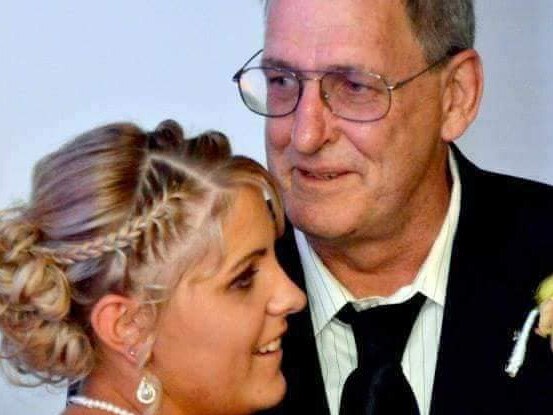

Kaylah Johnson used to talk to her dad Terry Lloyd every day. It was often for inspiration, occasionally support, or just to hear the voice of someone she knew would always have her back.

“You know, when something’s going on in your life and you want to tell him or ask advice – Dad was always who I would go to, he was the number-one person that I knew I could talk to about absolutely anything. Now I don’t have any of that. So it definitely is a big, big loss.”

She and her six siblings can no longer call him – all that is left is an agonising state of being stuck between grief and disbelief.

“We can’t have a funeral. We can’t have a memorial because there’s nothing – there’s no answers for us.

“There’s so many theories that run through your head, especially because our dad had bipolar and was in a manic state when he went missing,” Johnson, who lives in Wandoan, in Queensland’s Western Downs, says.

The questions have been the same the whole time he has been gone. Is he still out there? Did he really leave of his own free will? Or did he run into the wrong person?

“You always hear of missing people but until it happens to you, you don’t understand the impact of what it actually does,” she says.

On November 24, 2015, Terry Lloyd, 51, left his Goondiwindi, Queensland, home and never returned. He told one of his daughters he was going for petrol and said: “I love you.”

The following day the last known sighting of him occurred at a petrol station at Narrabri in NSW, more than 200km away. His car was eventually found on December 2, crashed into a tree in the Pilliga Forest about 150km south of Narrabri. The impact was not thought to have been life threatening, and no blood was found at the scene. His glasses had been left on the back seat, but his wallet has never been located.

Searches of the dense bushland surrounding the area found nothing, leaving police and his family with questions and no answers.

Intriguingly, filters for his roll your own cigarettes were found at the roadside.

Johnson dreads getting the phone call that would end the mystery. But equally, no phone call means she may never know what happened.

The possibility he is alive is remote, but not completely out of the question. Over the years the chance of a reunion has played on her mind, as have the emotions that would come rolling in if she ever saw him again.

Coming face-to-face with someone who disappeared so suddenly wouldn’t necessarily be as joyous as it’s depicted in the movies.

“Someone recently asked me, if he came back, would I be angry … but how can you be angry at him? He was not himself when he left. Bipolar can be a cruel thing, and even though there’ll be that anger there, it’s not him, you can actually take the anger out because he never intentionally did that to us.”

It’s a loss that has taken years to grapple with and try and explain, but often Johnson is lost for words, especially as she tries to tell her own young children why their grandfather isn’t around.

“We just kind of have to put it to the side. Something may happen one day,” she says.

Former police officer turned investigative journalist Meni Caroutas’ latest podcast, NewsCast’s The Missing Australia profiled a number of different cases and produced some extraordinary possible breakthroughs.

Following the release of an episode examining the grisly 1965 “baby in the post” case in Darwin, a Northern Territory family came forward to say they believed the murdered infant was a relative.

And Caroutas revealed the existence of text messages in the Gordana Kotevski case that showed names of suspects that police are now actively reviewing in relation to the 16 year old who disappeared from Charleston, near Lake Macquarie, in NSW, in 1994.

He details the journey families go through when a loved one abruptly vanishes from their lives. In Australia, that’s on average every 15 minutes.

“It’s a shocking statistic, and while most people are found quickly, for those who never return the impact on family and friends is devastating,” Caroutas says.

He says families have described it as an “emotional form of torture”.

“For every one person who goes missing, up to 12 people are adversely affected.

The unexpected loss of a loved one can have significant implications for those left behind,” he says.

Sadly, the families of Robert Simmons and Terry Lloyd know this all too well.