Fraser Anning avoided risk of fighting in Vietnam War by joining Citizen Military Forces

Controversial Senator Fraser Anning frequently invokes the ANZAC spirit. But in the days of national service, he made a decision to join reserves who would not serve in the Vietnam War.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Exclusive: Fraser Anning avoided the risk of fighting in the Vietnam War by joining a bush reserve unit that was exempt from being sent overseas to battle.

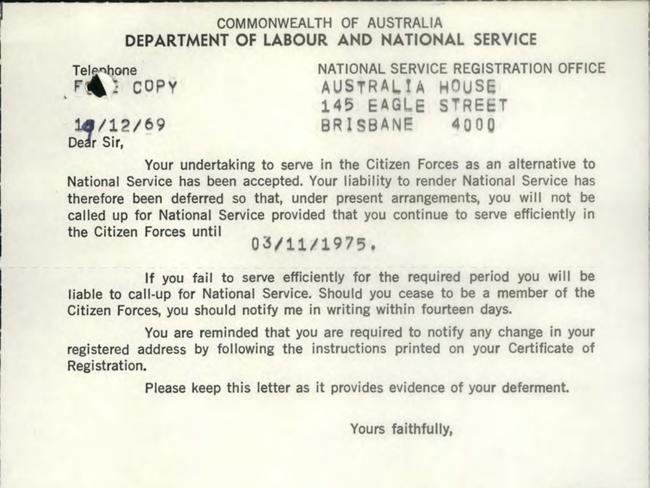

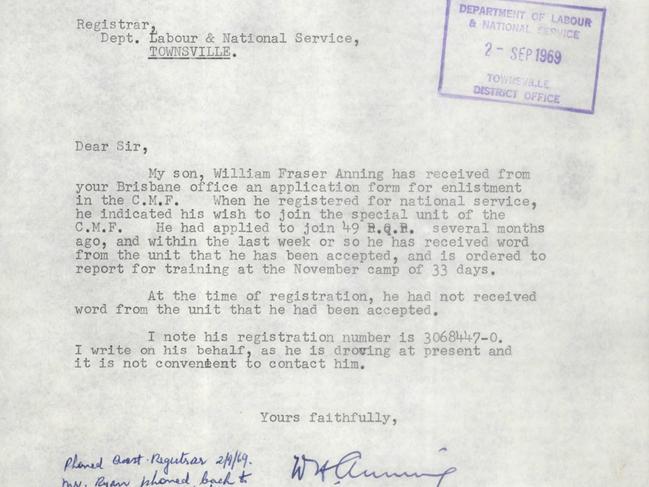

National service registration records obtained by News Corp Australia show when young Fraser Anning was summoned to register for national service in 1969, at the age of 20, he immediately applied to join a Citizen Military Forces Special Unit.

Senator Anning was approved to join the 49th Battalion of the Royal Queensland Regiment, which like all reserve units at the time was excused from war service.

The anti-Muslim, pro-gun independent Queensland senator, who often invokes the ANZAC spirit, told News Corp Australia it was his understanding he was liable for war service but his number never came up.

“My brother and I particularly wanted to get out of the bush and particularly wanted to go over there,” he said. “We always intended to get out of the bush and go over there and do our bit.”

It was put to Senator Anning that if he wanted to go to Vietnam, he could have simply volunteered for the regular army. “OK, well that’s what we thought we were doing when we put our hand up and they put us in the 49th Battalion,” he said.

However, on his national service registration document he fills out “Form C”, which offered an alternative to full-time national service and required that he attend just 33 days’ training each year over a five-year period.

The reason he gave for seeking an alternative on Form C was: “I live in a far distant locality.”

As the Australia Defence Association notes in a discussion paper on the national service scheme: “Those already serving for a minimum of five years (effectively not nominally) with the defence force reserves were otherwise exempt from national service. “

Senator Anning, censured for hateful remarks he made after the Christchurch massacre, tweeted last year: “Our ANZACs fought so that we could enjoy freedom of speech, sovereignty, peace and prosperity in our lives. We should stand up with the same bravery and courage as they did to preserve this or else Australia is gone.”

Between 1965-72, all Australian males aged 20 were required to register for national service. One in 40 would enter a birthdate ballot which required two years’ full-time service.

Of the 521 Australians killed in Vietnam or dying from wounds after they returned, 202 were conscripted national servicemen sent to war by ballot.

Senator Anning lived on remote Wetherby station in north-central Queensland, between Hughenden and Julia Creek and on his registration form gave his occupation as “jackaroo”.

Senator Anning’s father, William, appeared anxious to confirm his son’s acceptance into the Citizen Military Forces, writing in August 1969 that a CMF application form had been received but that Fraser was “droving at present and it is not convenient to contact him”.

During Vietnam, full-time servicemen referred to reservists as Koalas, meaning they “can’t be exported or shot at”.

The senator, who has announced his Conservative National Party will contest seats across the nation, attended his first 33-day training in Townsville in late 1969.

National service was suspended in December 1972 upon the election of the Whitlam government, meaning Senator Anning did not need to complete his service.

As it happened, Senator Anning’s birthdate would not be called in the tenth national service intake announced in September 1969. Even if it had, his status as a reservist would have ruled out deployment to Vietnam anyway.

Neil James, executive director of the Australia Defence Association, examined the senator’s registration form.

“Like tens of thousands of other young men in that era, he chose to do five years part-time service in the army reserve and not two years full-time service in the regular army,” he said. “What this meant was he wasn’t liable for deployment to Vietnam.”

Senator Anning claimed that under the Defence Act 1964, the CMF could technically have been called out for foreign service, but Mr James said: “It was never planned the CMF would go.”

The Queensland hotelier was elected to the Senate on the One Nation ticket on 19 votes after Malcolm Roberts was disqualified and immediately became an independent.

He is regularly in full voice about the meaning of service, last week tweeting: “Good men died for our right to freedom of speech and I will always defend it.”

He also posted, upon announcing his party’s election bid: “Australia is igniting the flames of liberty and patriotism that once stood strong in this country”.

The Australia Defence Association’s discussion paper states that those who (unlike Senator Anning) were balloted for national service could try to defer if they were undertaking tertiary study or on compassionate grounds.

Some were able to defer until the National Service Act was suspended in late 1972.

It notes: “Throughout the 1990s and 2000s many of our elected male members of parliament who turned 20 during the 1965-72 period fell into this deferment group — a fact not lost on many Vietnam veterans.”

Senator Anning reiterated that he “would’ve been quite happy to go over there. In hindsight, it probably would have been a silly mistake, but when you’re 20, and I was professionally shooting at the time, it seemed like a much better option than chasing cows around all the time.”