What Australia doesn’t get about Queensland

As hard as they try, southerners will never understand what makes Queenslanders tick. And the federal election was the perfect example, writes Michael Madigan.

Analysis

Don't miss out on the headlines from Analysis. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WE CAN amuse them, infuriate them and sometimes even charm them, but our one constant is that we never fail to mystify those southern folk, who periodically gaze northward and ponder: “What the hell is it with those Queenslanders?’’

We may not be the most populous state in the nation, but we are the orneriest and when we swing, we swing hard.

Queensland is always a conundrum, the joker in the nation’s political pack that can leave pundits staring on in slack-jawed amazement at our spectacular zigs and incomprehensible zags across the electoral landscape.

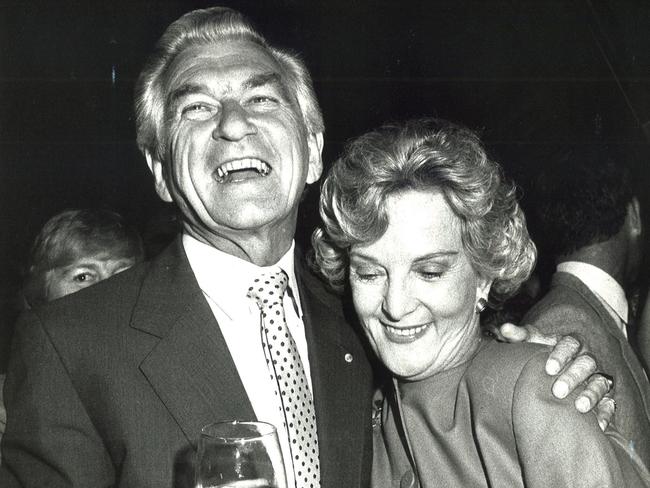

Federally, we can vote Labor, as we did in the 1990 Bob Hawke/Andrew Peacock election with 50.2 per cent of the vote going to Labor.

We did it again in 2007, when one of our own, Kevin Rudd, went to the Lodge with 50.44 per cent of the vote.

But if Queenslanders generally lean to the Conservative side, we never get too sentimental about it, as Canberra-born former premier Campbell Newman learnt four years ago.

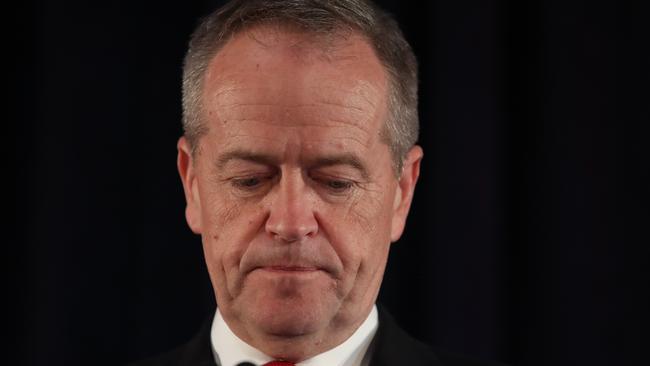

On Saturday night, we were on the rampage again, confounding Australia by snatching the unlosable election out of Bill Shorten’s hands and handing it to a stunned Scott Morrison.

Morrison called it a “miracle”,’ possibly without realising the “miracle’’ has been occurring since federation when Queenslanders first began puzzling southerners by splitting in two (one side south of the Tropic of Capricorn, one side north) on whether we should even form a nation.

The folk of the far-north were already so disillusioned with Brisbane that they figured they would get a better deal off Melbourne under a federated Australia, and gave the idea the tick.

The folk of Brisbane and the south-east, suspicious that their power would be diluted by an intrusive southern capital, voted No.

To long-time political commentator and senior lecturer at the Griffith University Dr Paul Williams, that federation vote set a mood to last a century.

Those early regional Queenslanders working up north planting crops, herding cattle and mining for gold with shovel and pick had a mind all of their own, and they branded it on the state.

Despite some pretensions to refinement in inner-city Brisbane in recent decades, it’s never rubbed off.

We’re hard-bitten, practical, rugged and rustic with a still deep connection to the soil, which has little of the polished gentility of Victoria’s western districts pastoral folk, but still manifests itself in the ramshackle shape of a hard-drinking, blunt-talking western Queensland grazier.

To Williams, Saturday night was no aberration, but merely a confirmation of tradition.

Bill Shorten’s fatal flaw was to underestimate the regional Queenslander whose world view stems not from deep contemplations on the moral imperative of addressing climate change, but from the practical imperatives of day-to-day existence.

“The regional Queenslander looks at Bill Shorten and thinks; “what we do up here is we mine, and you don’t like mining!’’ Williams said.

That uncomplicated view of the world was magnificently articulated by Mackay City Councillor Martin Bella as the Greens convoy protesting the Adani Coal Mine wound its way into the city in late-April, just three weeks before election day.

Bella, a powerfully built former rugby league international, stood up in the tray of a four-wheel-drive and fired the crowd with a declaration of war against the “anti-fishing, anti-mining, anti-farming’’ world of the inner-city Green and Labor voter, sneeringly dismissing their promises of job opportunities in the brave new world of eco-tourism and renewable energy.

“Amid all their trite statements that we can do this and we can do that, there is not one consideration for real economic concerns, not one consideration for the fact that we need to make a living, that we need to feed our families,’’ Bella roared. The crowd loved Bella. They didn’t love Bill Shorten.

Williams saw Morrison as a Queensland “brake’’ on the swing that most commentators believed was coming for Labor on Saturday, but Morrison proved himself to be far more than a brake.

Labor’s message fell flat not only in the Queensland regions, where the majority still live, but also in the homes of the state’s capital.

“You look at this election and you see it was not just regional Queensland – the whole of Queensland did not like Bill Shorten.’’