Death of Bob Hawke: How former PM shook the nation awake

Choose your Bob: larrikin, drinker, abstainer, womaniser, blubberer, negotiator, unionist, backstabber, top bloke, statesman, false prophet. Whichever, few could take issue that he was the founder of modern Australia.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Bob Hawke

December 9, 1929 — May 16, 2019

Choose your Bob: larrikin, drinker, abstainer, womaniser, blubberer, negotiator, unionist, backstabber, top bloke, statesman, false prophet. Whichever, few could take issue that he was the founder of modern Australia.

After the Menzies-era torpor, the short-lived and erratic Whitlam years, the failure by Malcolm Fraser to nail his conservative storyline, Bob Hawke — having replaced Labor leader Bill Hayden in February 1983 in a party coup — would shake the nation awake.

But first he had to explain himself. On the evening of Hayden’s overthrow, Hawke sat down with Richard Carleton on ABC’s Nationwide program. “Mr Hawke, could I ask you whether you feel a little embarrassed at the blood that’s on your hands?” asked Carleton.

Hawke: “You’re not improving, are you? … If it’s a question, Mr Carleton, of the electorate having to choose between your stupidity in such a question as that, and my integrity, I have no doubt where their belief will fall.”

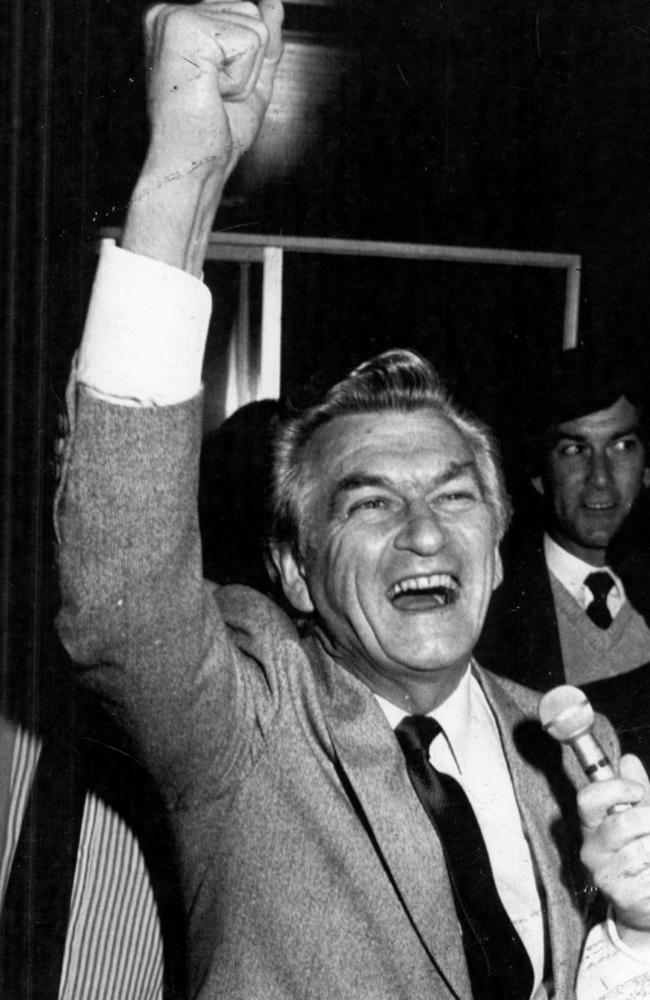

A month later, Hawke led a landslide victory over a tired Fraser government and would become Labor’s longest-serving prime minister.

By the end of 1983, the Hawke government had floated the dollar and deregulated the financial markets. With his treasurer, Paul Keating, Hawke set about up-ending traditional Labor values by privatising Qantas and the Commonwealth Bank, and ending trade protection for some Australian manufacturers.

In doing so, Hawke was doing two things: selling the farm and telling Australia it had to join the world.

Hawke was a household name long before he became PM, both as president of the ACTU (elected 1969) and as federal president of the ALP (elected 1973). So much so that Blanche d’Apulget, his later wife, produced a 418-page biography of him in 1982.

It is what is not said in that biography, the first of two by d’Apulget, that is slightly excruciating in hindsight, given that it is now known they had been on-off lovers since 1976. Hawke’s wife Hazel was treated as an afterthought.

That Hawke would one day become prime minister seemed inevitable — even if a bitterly disappointed Hayden said “a drover’s dog could lead the Labor party to victory” over Fraser.

Just before overthrowing Hayden, Hawke — who since 1980 had been the Member for Wills as he readied his political trajectory — had been instrumental in negotiating the Accord, an agreement between the ALP and the ACTU which set the grounds for superannuation, Medicare and enterprise bargaining.

Hawke had followed Margaret Thatcher’s lead in deregulating markets, but not her attempts to limit the power of unions. The Accord was a trade-off to show that Labor could work with, and not be beholden to, unions.

Hawke would explain: “The concept is we would provide improvements, particularly in health and education, which (unions) would regard as an offset to (demands) to increase money wages … that meant they were protected, employers didn’t have to pay as much, so it increased their competitive position. That was the overall concept of justice all around.”

Under Hawke, Australia was changing and moving.

The Early Years

There were some strange divinations about baby Bob, born in 1929 in Bordertown, SA. The hospital’s matron commented that there was “something special” about this kid. The baptismal priest said the same. His father Clem Hawke said there was something in the “configuration of his features” and the way he carried himself in the crib.

Clem and his wife Ellie, devout Methodists, were in little doubt. “We thought he was destined for a great future, even then,” Clem said.

When Hawke was 10, his older brother Neil died, at 17, from meningitis. It left Clem and Ellie so bereft they decided to move away to Perth, where Hawke was educated at Perth Modern School and took law at the University of WA.

He would win the uni’s speed-drinking competition and, as d’Apulget noted: “Within a few years the world was to know of Hawke’s prowess with alcohol: at Oxford (as a Rhodes Scholar) he drank Two-and-a-half pints of beer in 12 seconds and was entered in the Guinness Book of Records.”

Hawke did not want to pursue a straight law career and worried he might end up a legal academic. Though he’d never held a full-time job, he became interested in workers’ rights. He took a job with the ACTU preparing legal argument for the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission and quickly won national pay rises that marked him as a rising union star.

By then based in Victoria, in 1963 Hawke took a shot at a federal seat of Corio but fell short. It was arguably his advocacy as ACTU president that led to bans on the South African rugby and cricket teams touring during Apartheid.

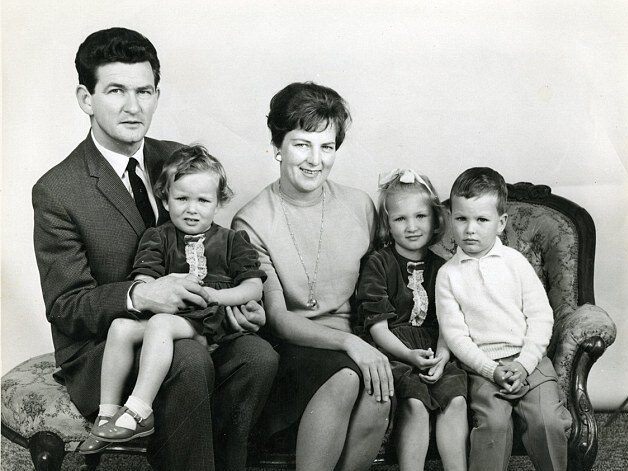

In 1971, Hawke was named Victoria’s Father of the Year. He appeared embarrassed and his wife Hazel could barely conceal her derision.

By then, he was seeing little of Hazel and their three children (a fourth, Robert Jnr, had died shortly after his birth in 1963) and was being propelled from drinking sessions to bedrooms in what he would call a “rock style” existence as both ACTU boss and ALP president.

In 1974, Frank Sinatra got Hawke’s notice when he complained about media attention. Sinatra said onstage in Melbourne: “And as for the broads who work for the press, they’re the hookers of the press. I might offer them a buck and a half. I might not.”

Sinatra’s three coming Sydney concerts were cancelled and the TWU refused to refuel his private plane. Hawke let his power be known, telling Sinatra via the media: “If you don’t apologise your stay in this country could be indefinite. You won’t be allowed to leave unless you walk on water.”

Hawke, the deal-maker, met Sinatra’s attorney and the US ambassador (who’d expressed concern Sinatra was a “hostage” of Australia) for four hours over Chivas Regal and cigars, after which Sinatra agreed to a lukewarm expression of regret. The tour continued.

Hawke’s intellect was in no doubt, but his alcohol problem — tempered by failed attempts at sobriety — would become so acute there would be doubts he could would be able to fulfil his ambition to lead Australia. But from 1980, from the time won Wills, he stayed sober for 13 years.

Hawke Takes Charge

IN 1983, PRIME MINISTER Hawke took Australia to the world. And we were beating it. The America’s Cup victory saw Australians staying up all night and Hawke declaring: “Any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up today is a bum”. His popularity would never be greater but he was hiding a fragility that may have come from his alcoholism.

His emotions sometimes took hold. He cried at the Tiananmen Square massacre; he cried at his philandering.

In 1984, the National Times published revelations on a minor drug charges relating to his eldest daughter, Susan, which were overturned and which Hawke regarded as a gross intrusion into his private life. Yet Hawke’s tears were likely for his youngest daughter, Rosslyn, who was fighting heroin addiction.

“You don’t cease to be a husband,” he said, as the tears flowed. “You don’t cease to be a father. My children and my wife have a right to be protected in this matter.” He then, according to d’Apulget, worked into a meeting with Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad and wept in his arms.

“The staff were appalled,” she wrote. “The Prime Minister had collapsed.” Mahathir was clearly not impressed. Hawke would cry again two years later, when Malaysia hanged Barlow and Chambers for heroin trafficking. Hawke called it “barbaric”.

The main achievements of Hawke’s prime ministership came early with the pay-offs from the Accord. Then he trailed off. He would promise national land rights and a treaty but fail to deliver; and he was no soft touch on a wave of Cambodian refugees, calling them queue-jumpers and saying that, “Bob is not your uncle on this issue.”

In 1987, as Hawke prepared for his third election, he stated at Labor’s campaign launch: “By 1990, no Australian child will be living in poverty.” He looked down when he said it. Almost as if he was embarrassed. Something had gone out of his fight.

By some accounts, it was despair for Rosslyn, and worry for his relationships with his other children Susan, and particularly Stephen, who had sharply rebuked him for his Aboriginal affairs sell-out.

The Afterlife

IN 1990, after winning his fourth election, the undertaker came knocking.

In 1988, at Kirribilli House, Hawke had promised to hand Paul Keating the leadership after the 1990 election. Hawke went back on his word and Keating moved on him in May 1991. Keating lost the leadership ballot but tried again in December of the same year. This time he won.

Hawke was done. He’d had two cracks at Hayden and now it had happened to him.

Hawke and Hazel divorced he married d’Apulget in 1995. Hazel died from Alzheimer’s in 2013.

Keating would savage Hawke, saying that for five years of his leadership — that is, most of it — he was dysfunctional. “The job of the leader is to nourish the government with ideas. You run the debate, you set the framework and push on. In the end, most of that job fell to me in those years,” Keating said in 2014.

In 2015, Hawke gave an unexpected assessment of Keating.

“I am really basically extraordinarily grateful to Paul because if I hadn’t been thrown out then, I would not have had the opportunity of marrying the woman with whom I had fallen in love,” Hawke said.

Perhaps Hawke meant it would have been inappropriate for a prime minister to divorce in office — possibly a nod back to his Methodist mum, Ellie, to whom he had once promised he’d stop drinking and had not kept his word.

Either way, Hawke had a touch Keating never had. And unlike Keating, he never lost an election.

Hawke would have business dealings with the military junta of Burma, claiming some of what they were doing was “positive”; he was also a strong proponent of nuclear energy and Australia as a viable place to build a radioactive waste dump.

In “The Hawke Ascendancy”, Paul Kelly wrote of Hawke’s first overseas trip as PM. In Jakarta Hawke “went soft on self-determination for East Timor”; he “weakened the party’s anti-uranium stand”; and “supported President Reagan’s policies in central America”.

This showed how Hawke played politics. To him, the most important principle was pragmatism.

The Oxford Companion to Australian Politics, in its final line about Hawke, states: “While the Hawke government was the most successful of post-war Labor governments, it has left the Labor party unsure of what it stands for.”

That was published in 2007. They did not anticipate the further confusion of Kevin Rudd.

Bob Hawke was a true Labor man, but he did not wear its straitjacket. He made it permissible for party types to define themselves more broadly.

Originally published as Death of Bob Hawke: How former PM shook the nation awake