TIM Watson-Munro has spent much of his career with murderers, sexual predators, hit men and those who kill in fits of rage, and the criminal psychologist admits he knows more than is good for him when it comes to the dark side of human nature.

He was struck by the man’s ordinariness.

I was surrounded by an ambience of menace and danger every day

It wasn’t long, however, before he met real evil in the form of a weather-beaten prisoner whose crime 20 years earlier encapsulated the most repugnant features of a sexually driven killer.

Johnny Smith was reviled by his fellow inmates, a “sick dog” who even nudging 60 continued to repulse those who met him, including Watson-Munro.

Smith was a psychopath whose twisted fantasy of sexual control had reached its peak in the torturous murder of Sydney teen Margaret Thomas on April 11, 1958.

A dull man with a hatred of women, he abducted the 14-year-old from the dorm of the Methodist Ladies College in Burwood, brutally raped her then stabbed her 15 times in a nearby park.

“Even writing about him 40 years on, it still chills me to the core,” the now 65-year-old Watson-Munro says. “I found it difficult to stomach the bloke. He deserved every year that he got.”

EXCLUSIVE: MICK HAWI AND THE JAILED BIKIE GANGS

Watson-Munro has spent a large part of his life in the company of killers. As one of Australia’s foremost criminal psychologists, he has assessed more than 30,000 persons of interest in his 40-year career, among them more than 200 murderers.

At the height of his career in the 1980s and ’90s, he was one of the nation’s top criminal psychologists, appearing as an expert witness on major cases including mass murderer Julian Knight, the “Black Prince of Lygon Street” Alphonse Gangitano and fraudster Alan Bond.

His rise was meteoric — big cases, big bucks and a big ego followed — but life in the fast lane caught up.

The toll of working with so much depravity, together with the death of his first wife, his mentor and a spiralling $2000-a-week cocaine addiction, saw his brilliant career implode in 1999.

Struck off in 2000, Watson-Munro spent a tough few years in the wilderness, but after a long road of treatment and recovery, he was readmitted to his profession in 2004. Hitting rock-bottom, he says, has made him a better practitioner, more insightful to the dynamics of crime and rehabilitation.

Almost 20 years clean, he’s written a new book, A Shrink In The Clink, documenting the spectrum of criminal psychology he’s encountered during his career. It’s a fascinating read but not for the faint-hearted.

He began his career in 1978 in Parramatta jail, then the toughest prison in the country. A dumping ground for lifers and intractables, for the son of a physics professor who’d lived a fairly privileged life it was a “trial by fire and ordeal”.

“On my first day, the prison governor Harry Duff said: ‘It’s nice to meet you son. Remember this now you’re working here, if you can be conned, you can be f…ed. Have a good day.’”

Surrounded by an ambience of menace and danger every day, Watson-Munro learned to navigate the prison’s complex web of intrigue and brutality thanks to the steady hand of Duff.

“He was in his 40s and he’d been a tough knockabout screw before he became a governor,” he says of his then mentor. “He just had a great sense of timing and a capacity to intuit situations.

“I learnt so much from him about handling the dark side of human nature.”

After pioneering a successful recidivist program at the prison, Watson-Munro moved to Melbourne to work with forensic psychiatrist David Sime.

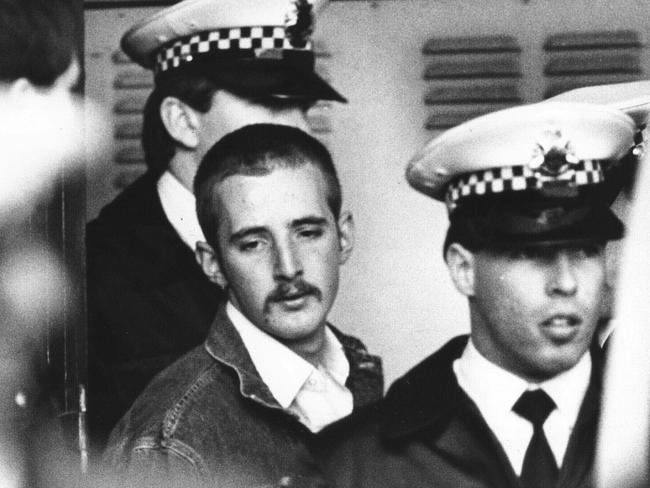

Initially, he interviewed people who had broken the law, writing psyche reports for court. Sime began throwing him bigger cases. Then along came Julian Knight.

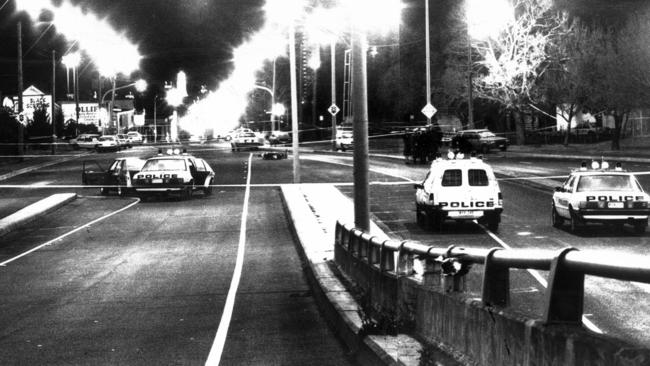

The Hoddle St massacre was one of the most harrowing crimes Watson-Munro ever worked on and even today the case haunts him, not only because of the number of people Knight killed, but because of the complexity of his thinking at the time.

Knight, who had been discharged from the Royal Military College at Duntroon 16 days earlier, was playing out a delusional combat fantasy on the night of August 9, 1987, when he opened fire on passing cars in Hoddle St.

In less than an hour, he’d killed seven people and injured 19.

“I saw him within a week or two of the crime being committed, and I didn’t know if he’d be hostile, angry, psychopathic,” he says.

“What I found was a bewildered 19-year-old kid in a rubber room. He was very deferential and polite.”

Knight was suffering severe depression, fury, frustration and social withdrawal at the time he became a mass murderer.

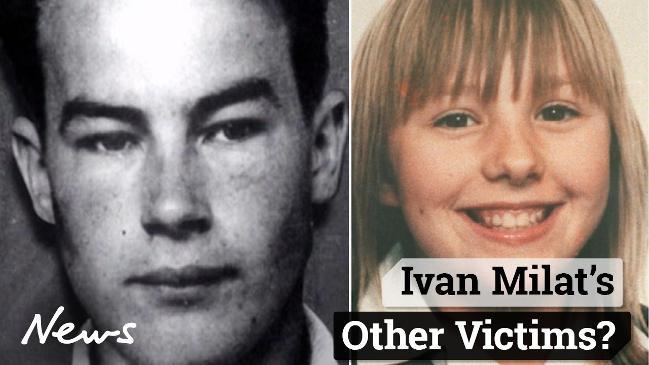

He was not insane, he knew what he was doing, but the psychology of his crime was different to a psychopath such as Johnny Smith or Ivan Milat.

“Mass murder is not sexual necessarily, it’s rage. But serial killing, there’s generally a sexual component to what they do,” he says.

“Julian had an explosion of frustrated rage and tragically there were three guns at home given to him by his family.

“What he did was hateful. He destroyed not only those lives and the families of the deceased, but Melbourne was irrevocably changed by that event.

But he’s no Ivan Milat.

Milat was a malicious, calculating, psychopathic serial killer who abducted people on the Hume Highway and he did it over a period of time. He would have kept going, I believe, had he not been detected through one of the tourists that got away.”

Some years ago, Watson-Munro was approached to see Milat but declined.

“He’s always looking at angles, but I had no interest in meeting this bloke. If you look at his crime and his behaviours since he’s been in custody, what hope has he got of rehabilitation,” he says.

It’s not a criminal psychologist’s job to determine innocence or guilt.

The fundamental issue Watson-Munro is asked to professionally adjudicate is criminal culpability. Was the person aware of his or her actions? Were there mitigating factors? Was their knowledge of wrongdoing compromised by psychological factors?

“These days I much prefer seeing people who’ve been charged with drink-driving. Harry from Hornsby who drives home one night, he’s had a few too many after golf and has blown .07. You’ll never see him again, there’s an explanation for it.

“Murder cases are hard work, not only because of the content of what you’re doing, the implications for the offender and the victims, but inevitably you give evidence, you’re cross-examined in the Supreme Court and it can be very robust.”

Not all killers are intrinsically evil. Some find themselves in court for a momentary lapse of judgment. There’s a spectrum or gradient of “badness”.

But pure psychopaths — those who by definition have no remorse, no empathy, no prospects of changing — are out there, often camouflaged by their ordinariness.

“I think there are serial killers floating around the streets of Australia,” he says.

“You don’t hear about them because often their victims are so anonymous, kids that run away from home that are never seen again, homeless people.” Most offenders, he says, fall somewhere between the extremes.

“When you get someone referred to you who’s led this seemingly blameless life, they’ve been prosocial, might have kids, a job and all of a sudden they’re looking at 20 years of jail because they’ve lost their shit, I wonder about the trigger points.

“I understand them conceptually but what is it at that moment in time that causes you to cross the Rubicon in such a permanent, dramatic way?”

Eerie Google Maps image shows Bondi terror car at Akrams’ home

Google Maps street view reveals the car used in the deadly Bondi terror attack was parked outside a Bonnyrigg home belonging to Sajid and Naveed Akram.

Jewish experts fly in on sacred mission for Bondi victims

Volunteers who deal with the “absolute worst of the worst” have travelled from three continents to recover every drop of blood from the crime scene.