Way We Were: Mine disaster that decimated Mount Mulligan

An explosion heard 30km away was the death knell for a fledgling Queensland mining community, with a quarter of its population perishing.

CM Insight

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM Insight. Followed categories will be added to My News.

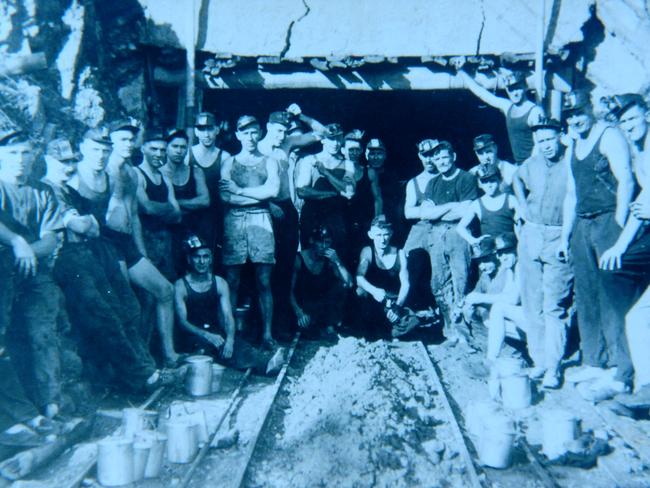

Pupils at Mount Mulligan school were on parade listening to their headmaster give the morning devotional when an enormous explosion shook the little north Queensland coalmining settlement.

Most of the children would never see their fathers again.

It was 9.25am on September 19, 1921, when the fledgling Mount Mulligan community became the scene of Queensland’s worst mine disaster. From the school, black dust could be seen erupting from the foot of the mountain 800m away and pieces of timber were flying high in the air.

Underground, an explosive on top of a large block of coal had gone off prematurely and 75 miners didn’t stand a chance.

The blast was heard up to 30km away. Outside the mine entrance, grass was smouldering and debris was flung 40m.

Everyone in Mount Mulligan heard the explosion, although some were not immediately alarmed. Doris Watson, in the company office 500m from the mine entrance, thought it was routine blasting until she saw people running towards the mine; and Bruce Mackey, about 1km away, thought it was blasting clay for the brickworks.

With a population of only 360, the tight-knit community had lost almost a quarter of its residents in a flash, and not a single household was left untouched. About one adult in every three, or one in every two men, had perished, leaving 40 widows and 83 children fatherless.

Within minutes of the explosion, a heroic rescue effort was underway and for the next five days the locals, with the help of hundreds of volunteers from the surrounding district, risked their own lives looking for survivors and retrieving bodies.

Government geologist Edgar Smith reported that he considered that going into the mine after the explosion was one of the bravest things imaginable and it was remarkable that more men were not lost. Today, a mine would likely be sealed after a large-scale explosion.

Grieving widows waited at the mine entrance for days to identify the bodies as they were brought up from the mine, many of them severely burnt. Just two weeks earlier it had been decided to establish a cemetery on the outskirts of town and now it was filling quickly, as grief-stricken women buried their menfolk: “One or two suffered an almost complete breakdown and were consoled by their sisters in trouble.”

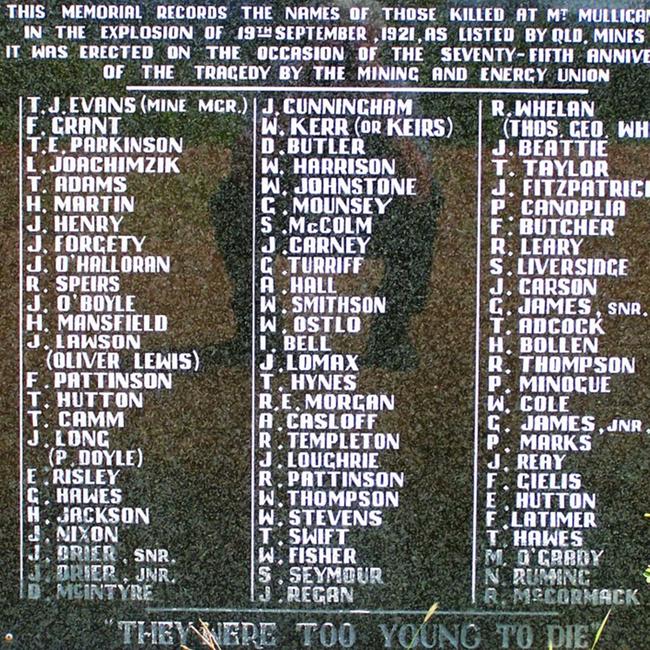

Four victims had been standing at the mouth of the pit outside and another 70 bodies were underground, although the exact number will never be certain.

Five months after the disaster, it was found that a 75th victim had crawled into a narrow tunnel away from the search area and historian Peter Bell, who interviewed witnesses 55 years after the disaster, believes there could have been 76.

He says that the organisation of most mines was so haphazard that in the event of an accident underground, the precise number involved was rarely known, and the possibility of bodies remaining undiscovered was very real.

Chillagoe Limited, the owner of the mine, was not known for its record keeping and had no roster of who was in the mine on that fateful day. Some were being buried while bodies were still being recovered so there was never a precise count.

Ironically, the Queensland mine had been considered one of the safest of its time. There was no indication of gas leaks, which was fortunate as the miners were still using carbide lamps with exposed flames for light.

The sense of safety encouraged dangerous practices, most of which didn’t come to light until the royal commission into the disaster found there had been careless use and storage of explosives.

Mr Bell’s research also revealed a possible problem with mine inspections. Mount Mulligan was the only Queensland coal mine and regional inspectors were more familiar with gold, copper and tin mining, than the dangers of coal.

The first coal deposits at Mount Mulligan, about 150km west of Cairns, were found under the mountain in 1907, and mining began in 1910 although it was another five years before it went into large-scale production.

Coal, previously shipped from Newcastle, was used for the Chillagoe smelters and the Cairns district railway.

After the disaster, Queensland introduced a Coal Mining Act which, among other points, banned naked lights in mines and introduced rules for the use of explosives in coal mines.

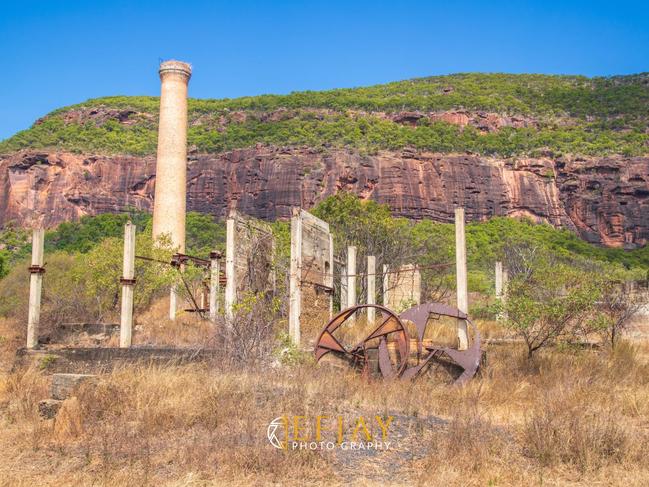

Mount Mulligan mine reopened four months after the explosion and eventually closed in 1957 when the Tully Falls hydro scheme was completed.

Townsfolk moved to Collinsville, useful machinery was removed and today it is a ghost town but, at the cemetery, a plaque lists the names of 75 miners who died in Queensland’s worst mining disaster a century ago.