Way We Were: Horrific moment Navy patrol boat demolished

After finding himself in the middle of one of the most destructive cyclones to ever hit Australia, the commanding officer of this Queensland-built Navy boat had to make a fateful decision.

CM Insight

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM Insight. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In the pre-dawn darkness of Christmas Day 1974, with powerful winds and driving rain that blasted paint from metal, the young Commanding Officer of HMAS Arrow faced a brutal enemy.

At 27, Lieutenant Bob Dagworthy was in charge of the Navy attack class patrol boat Arrow and its crew who, as custodians of thousands of kilometres of coastline, were accustomed to routine surveillance. Instead, they found themselves in the middle of one of the most destructive cyclones in Australian history.

Built at Queensland shipyards Evans Deakin in Brisbane and Walkers in Maryborough, Arrow was commissioned into naval service at Hervey Bay in 1968 and sent south before arriving in Darwin in September 1974.

Three months later, on December 21, the US weather satellite detected a storm brewing over the Timor Sea. It was soon upgraded to a cyclone named Tracy. For the next three days, Tracy wound its way around Melville Island, before heading straight for Darwin.

At 2pm on Christmas Eve, the Navy commander for Northern Australia ordered the patrol boats to recall crew and head to the cyclone buoy, about a kilometre from Stokes Hill Wharf, to ride out the approaching storm.

At 6.30pm, Dagworthy reported that they were secured to the furthermost buoy. At midnight, it appeared that the cyclone might blow itself out, but two hours later, all hell broke loose.

The force of the waves tore the Arrow from its buoy.

Visibility was nil. Petty Officer Les Catton bravely crawled to the forecastle and confirmed that the anchor winch had been ripped from the deck and the anchor chain was gone.

Life rafts disappeared overboard when waves breaking over the deck activated the hydrostatic release.

Then all went quiet. Sitting in the eye of the cyclone, Dagworthy expected it would be less ferocious on the other side and told his crew, “well, we’re going to survive”.

But it was far worse than what they had already endured. The wind and sea became more violent, the horizontal rain and sea spray actually blasting paint from the ship’s metalwork.

Waves were so high that they washed over the superstructure and the wind was gusting at up to 240km/h.

The radar and navigation system shut down and instruments failed. Then a giant wave hit and the intake for pumping water to cool the engines rose out of the water and took in air, causing an airlock that put it out of action.

The engines overheated and were ready to seize, leaving Arrow bobbing powerless on the boiling sea.

The young CO decided their only hope was to try and run the ship into the muddy mangroves of Frances Bay.

The roar was so loud he had to shout orders into the ears of the helmsman and engineer.

His plan was to edge the ship around to get a blind feel for where the mangroves might be, but, while gingerly manoeuvring, they were hit by another giant wave and the vessel washed sideways on to Stokes Hill Wharf.

Hammered by waves and with the engines likely to shut down at any moment, Dagworthy could see it was pointless trying to move it again.

He made a decision that no Commanding Officer ever wants to make – abandon ship. And that wasn’t going to be easy.

Every time a wave hit the ship, the surge brought it level with the wharf.

Those brief moments were a chance for crew members to leap from the ship.

Dagworthy stayed in the wheelhouse using what engine power was left to steady Arrow at the wharf. Les Catton made it safely but was hit by flying debris and knocked into the harbour. Ian “Jack” Rennie missed and fell between the wharf and the ship.

Soon, Arrow had taken on so much water it could no longer reach the height of the wharf and the escape route closed.

Dagworthy told the remaining crew to fully inflate their life jackets, take their chances and leap into the harbour.

He did the same and was washed under the wharf and pummelled on to the mud flats.

Rennie’s body was found that morning while Catton’s body was found under the wharf on Boxing Day.

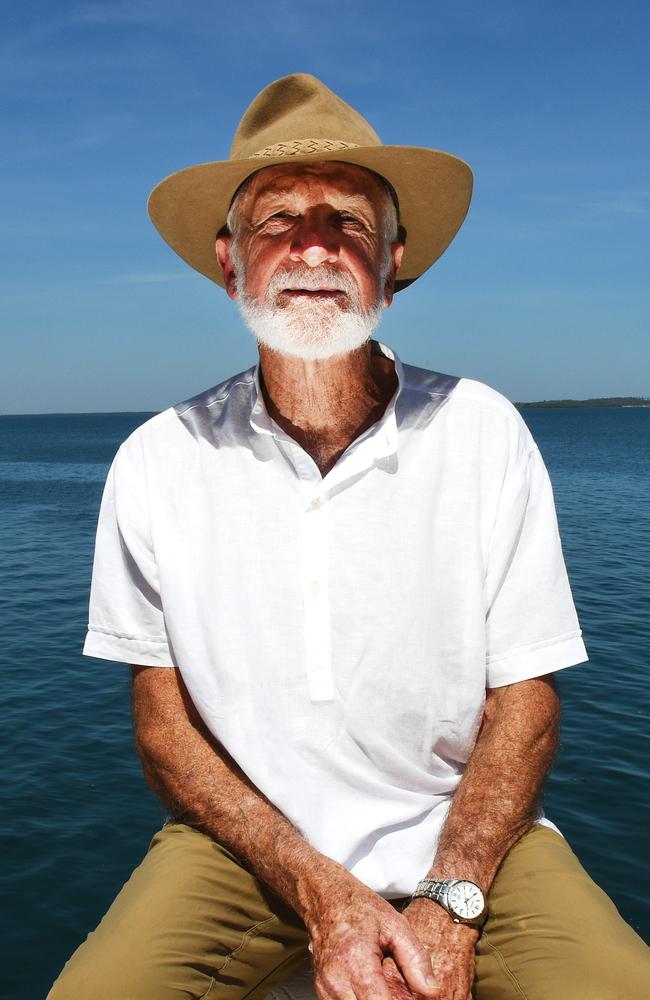

Having lost his ship and two seamen, Dagworthy expected his naval career was over, but the Board of Inquiry into the loss of HMAS Arrow praised him for his professionalism.

He went on to a long and successful career in the Navy and is now retired in Brisbane.

The Arrow was eventually broken up and sold for scrap.

Captain Dagworthy will honour Able Seaman Rennie and Petty Officer Catton at a Naval Association of Australia ceremony at the Jack Tar statue, South Brisbane Memorial Park, this Thursday, November 25, at 11am.