Town for sale, Allies Creek, has a fascinating history from boom to bust and everything in between

WHEN it went on the market for $500,000, this ghost hamlet in the Queensland outback made global news. Behind the headlines lies a fascinating story of two men’s determination to succeed, government treachery and heartbreak, writes Mike Colman.

CM Insight

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM Insight. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT HAS been raining on and off all day and the car slides from one side to the other as I drive along the gravel road. Cattle grazing on the verge look up dumbly as I pass, and I hit the brakes as a wild pig scurries across my path 50m ahead.

It’s early afternoon but the heavy skies and towering eucalypts combine to create an eerie light. The radio coverage has cut out about 10km back so I stick a CD into the sound system: “The Best Rock Anthems … Ever!” I can’t help smiling as the voices of Talking Heads fill the emptiness. “We’re on the road to nowhere …”

Then, 40 minutes, maybe an hour along the track, the thick vegetation clears and, like an oasis, a township emerges on the left hand side of the car. At first glance it looks like something out of a theme park or movie set; pristine, well ordered but without a car or person in sight. The only sign of life is a herd of kangaroos that bound away as I turn in and slowly make my way past what looks like a church towards a row of houses.

Pulling up, I find the town’s sole inhabitant, a 61-year-old man who gives his name only as Bob. He’s dressed in a tracksuit and faded cap and has the most magnificent wild, snow-white beard I’ve ever seen. At his feet stands a little scallywag of a dog named Jed.

I ask him how long he has lived in the town.

“Bout a year.”

“Like it?”

“Yeah, it’s good. Quiet. You can come and go. People leave you alone.”

I ask if he’ll give me his surname.

“No.”

How about a photo of him with the dog?

“No,” he says as he tucks Jed under his arm and heads inside his house. “I came here to get away.” Fair enough. You get the impression that people have come to live at Allies Creek for many reasons, and getting their name and picture in the newspaper isn’t one of them.

When news of an entire Queensland town being offered for sale for just $500,000 went viral last month it caused astonishment and bemusement around the world. And almost moved an 82-year-old Brisbane man to tears.

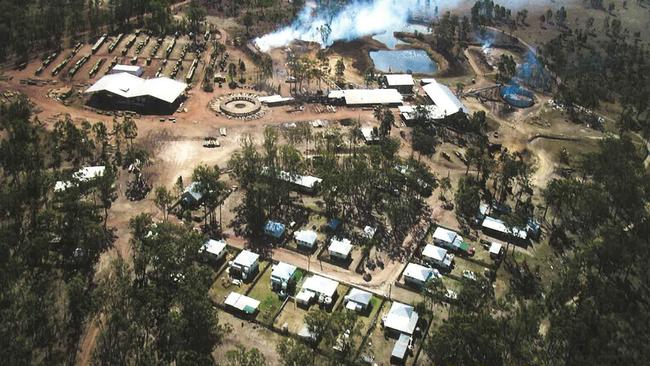

For those who read of the sale of the South Burnett town of Allies Creek on online news sites everywhere from India to Germany and the UK, descriptions and photographs of the tidy 12-house hamlet, complete with community hall, tennis court, helipad and fish-filled dam, may have conjured romantic visions of owning an idyllic private kingdom in the countryside.

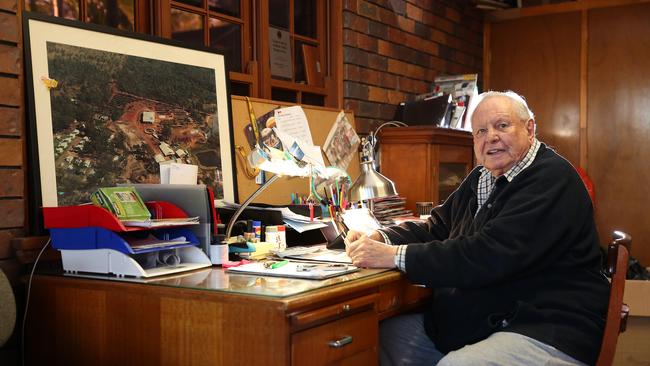

For retired businessman John Crooke, it only revived bitter memories of shattered dreams, heavy-handed government politicking, a highly successful business laid to waste, and the loss of millions of dollars.

“Just thinking about it breaks my heart,” he says as he sits in the garage of his Hamilton home thumbing through faded photographs of the township and the timber milling operation that his father Eric and Eric’s business partner Frank Straker carved from the wilderness more than 70 years ago.

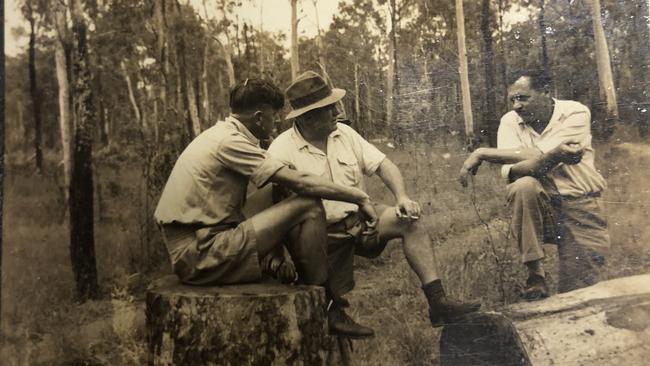

The two men had met through their work in the building trade in the 1930s. Frank came from a family of timber millers, and Eric, who ran his own wholesale building supply firm, was a customer and friend. With lumber a protected wartime industry, Frank did not join the military during World War II, but Eric closed down his business and enlisted in the navy. Becoming an expert in the detection of Japanese radar, he was seconded to the staff of US general Douglas MacArthur in Brisbane.

In 1945, with Eric soon to leave for the Philippines with MacArthur, the two friends met for a farewell drink.

According to John Crooke, Straker told Eric, “This war is almost over and when the soldiers come back the war brides are all going to want new houses. There won’t be enough timber for them. I want to start a company to cut it, mill it and supply it.”

“Father said, ‘put me down for half’,” Crooke says.

Straker went to the Queensland government’s senior forester Alan Trist with his plan. Trist, “a timber man and straight shooter”, pulled out a map and showed Straker a 50 acre plot of prime spotted gum forest near Allies Creek, 70km south of the citrus capital of Mundubbera.

“We’ll take it,” said Straker. The land was put up for public auction. Eric Crooke received a telegram in the Philippines. “Pleased to advise we have been successful …”

The two partners, who called their company Queensland Sawmills, won the rights to the timber “in perpetuity” and were granted a sawmill licence on the proviso that the timber be cut and milled on site.

In mid-June, 1945, Frank Straker and six workers climbed into two US Army surplus vehicles, including a tank carrier, and set off on the 360km trek north from Brisbane to Allies Creek.

After forging a 20km trail through the bush where the current gravel road still runs, they arrived on the isolated site and set about building a mill and a town.

“They put up tents and worked night and day 17 days straight, then had four days off and started again,” says Crooke. “They had no power, no water. They lived off goat meat that a local farmer sold them. They had fried goat, curried goat, fricassee of goat … Frank reckoned when it was over he never wanted to see another goat in his life.

“The first thing they built was the mill, with a barracks for the workers. Over the next two years they dug a dam to provide the water for three giant boilers and built the town.”

Fast forward 70 years and when news of the sale of the town began to circulate last month the backstory seemed almost too bizarre to be true.

According to the reports, husband and wife Lyle and Natali Williams had bought the town in 2008 for around $160,000 almost by accident when they attended an auction at the site after the mill had shut down.

“My husband and I came out here to buy machinery at auction and then bought the town,” Williams says.

“We didn’t quite know what to do with it.”

To those reading about the town’s sale the obvious assumption was that the mill had failed; that Frank and Eric’s dream to build a business and a community in the middle of nowhere had proved little more than a folly.

In fact, nothing could have been further from the truth.

At the time of its acquisition by the Bligh government 10 years ago Queensland Sawmills was a highly successful and sophisticated operation.

Just as Frank had predicted, the post-war building boom had relied on a steady supply of good quality timber, and Allies Creek was ready to deliver.

“It was a big risk at first,” says John Crooke. “They took on big loans and the first timber they milled had to be treated and left to stand for 12 months before it could be sold so there was no income for a year.

“Years later Alan Trist told us that he didn’t think they’d make it. He thought they’d go bust, but Frank was a genius sawmiller and father was a brilliant salesman so they made a good team. The mill burnt down in 1952 and they had to rebuild; there were some tough times but they made it through.”

John took over the business in the 1960s and oversaw a period of growth and technical advancement. At peak employment there were 65 workers living in 16 houses in the town, and a school for 20 pupils. Electricity eventually replaced the wood-fuelled boilers, computers and state-of-the-art machinery imported from Europe transformed production.

And the town took on a life of its own with intrigues and romances, fun times and tragedies, including the deaths of two children in a house fire and an entire family lost when their car careened off a bridge on the way back from Mundubbera.

“It was isolated out there so it was really its own community,” says Gerry Butler who lived and worked at Allies Creek with his wife Judith from 1982 to 1988.

“We’d go to each other’s houses and have Christmas parties and things like that. My son was born when we were there. He had his first birthday parties there. We used to play cricket and football on the tennis court and go yabbying in the creek. Everyone got along pretty well. I’d grown up in a big city so I found it pretty quiet but my wife really liked it. She was sorry to leave.”

By 2008 Queensland Sawmills was a major supplier of hardwood throughout Australia and overseas. As public taste changed, so did the company’s product line, from weather board to furniture and gymnasium flooring. The company used the technique known as “selective logging” instead of indiscriminate “clear felling”, meaning each tree felled had to be chosen and marked. Once an area was logged it was left to regenerate, providing an ongoing resource.

“We were turning over around $3 million to $4 million a year, we were very happy,” says John Crooke.

And then, with an election looming and Green votes up for grabs, the Bligh government pressed ahead with plans to extend national parkland in the North Burnett. Logging mills were acquired and shut down, in the words of Timber Queensland chief executive Rod McInnes, “to lock up a million hectares of forests to appease the conservation movement”.

The mill owners were summoned to Brisbane to negotiate for their futures. They tried to compromise, offering to reduce quotas and cut back operations but it was futile. John Crooke claims a government minister told them, “You blokes are missing the big picture. We just want to get re-elected.”

“At least he was being honest,” he says. “They told us we could keep operating the mill but we would have to do our logging 1000km away at Alpha and bring the logs in by truck. The timber wasn’t as good and the royalty we paid the government would be the same. We talked about setting up a mushroom factory or tyre recycling, but that wasn’t what we knew. We were loggers. They had us over a barrel. We had to take what they offered.”

The price agreed was confidential but Crooke will say it cost him and his family millions of dollars – not that it’s all about the money.

“That company had been part of my family for three generations and the same with the people who worked for us. Some of them had been with me for 40 years. Their fathers and grandfathers had worked for us. Some of them had never lived anywhere else. When I told them they had to leave they were shocked. There were a lot of tears. I feel like crying just talking about it.”

Lyle and Natali Williams moved into Allies Creek with plans to develop it into a caravan park. For several years they rented out houses for $100 a week plus electricity. Residents came and went for various reasons. Some to get away from city stress or broken relationships, others “for their health”.

When Lyle died four years ago and Natali moved to Mundubbera with their son Roger, she put the town on the market for about $2 million. By last year the price had dropped to $750,000 and looked to have found a buyer but that sale fell through, leading to last month’s international headlines of “the $500,000 town”.

Mundubbera property agent Danielle Meyers says she received interest from England, New Zealand and Australia. An offer was accepted from a potential owner who plans to turn the town into a fully sustainable “eco-community”.

“It is under contract,” she says. “We’ll know in about three weeks, but even if this sale doesn’t go through I expect to have a buyer soon. I could have sold it several times.”

Meanwhile, the town that Frank built waits silent and near-empty for its next owner.

From a distance the houses still look as good as they did the day the first families moved in, but the mill itself is derelict and rotting. An old rusty truck sits on flat tyres. Walls and ceilings have fallen in, although shift rosters and production targets are still on blackboards just as they were on the day the workers walked off the job for the last time.

“Reyanne, Mishell, Linda, Neale, John – don’t forget top saw. Gross m3, Our Aim 50m3 av/day …”

The din of saws and trucks and forklifts and workmates is gone forever. In its place is the laughter of kookaburras and the splash of ducks on the dam.

And the howl of the wind through the spotted gums, like the ghosts of Allies Creek.

mike.colman@news.com.au