AHS Centaur sinking marks 75th anniversary

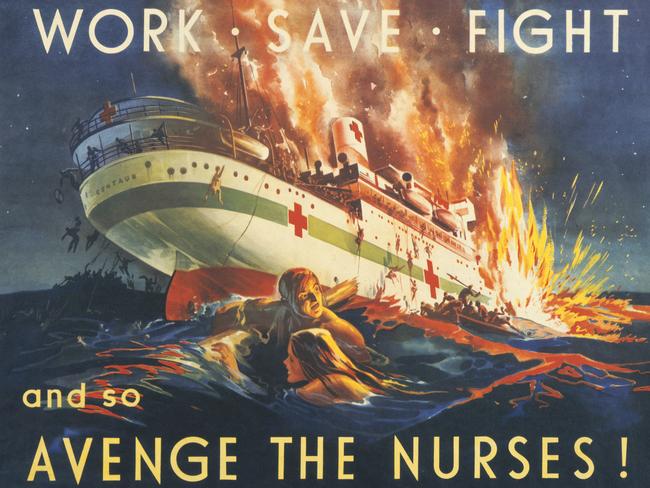

TWELVE nurses were among the 268 dead after a Japanese submarine torpedoed the well-marked Centaur hospital ship off the coast of Brisbane 75 years ago.

CM Insight

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM Insight. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HER friends were all dead, sucked down to a watery grave by the huge vortex created as the burning hospital ship Centaur sank in 2km of inky black ocean off Moreton Island.

Of the 12 nurses who had been sound asleep hours before as the defenceless white vessel cruised north along the Queensland coast, Lieutenant Ellen Savage was the only one who had not suffered a horrific death. She was still alive. Barely.

It was 75 years ago on Monday that the 30-year-old nurse from Quirindi, NSW, bobbed about in a thick oil slick trying to keep her head above water as she struggled towards a flimsy raft.

Dead bodies – the skin seared from their flesh – wood and metal debris surrounded her. Ellen’s ribs, nose and palate were broken, her eardrums perforated. Her body was one massive, agonising bruise.

A flying lump of wood had hit roommate Merle Morton in the head and killed her, and now Ellen had the herculean task of saving herself and trying to save those around her.

All along the east coast of Australia on Monday there will be commemoration services honouring the loss of 268 lives and the heroism shown among the 64 survivors after a Japanese submarine fired on the defenceless ship ferrying medical staff.

On the picturesque Caloundra Headland, opposite the cafes, restaurants and bars of a holiday paradise, the local RSL will hold a memorial service in Centaur Park, looking out to the spot of unimaginable hell all those years ago.

Japan has never admitted guilt, but their leading expert in submarine warfare wrote that the Japanese vessel 1-177, under Lieutenant Commander Hajime Nakagawa, was responsible.

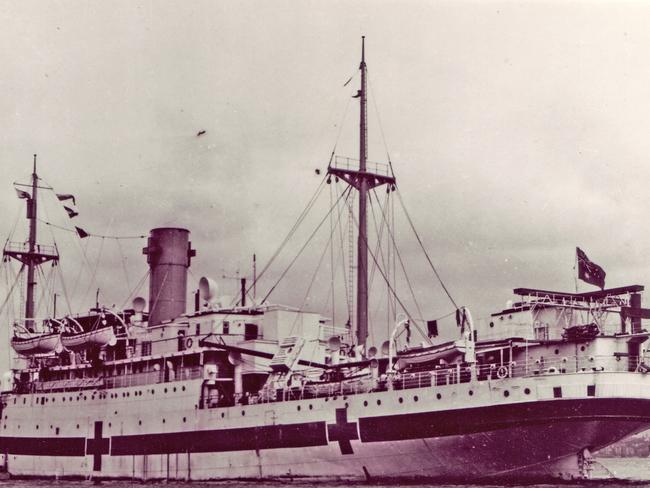

At the outbreak of war, the Scottish-built Centaur had been operating for 15 years between Western Australia and Singapore, carrying passengers and cargo.

In November 1941, it had rescued German survivors from the raider Kormoran after its battle with HMAS Sydney resulted in the death of 645 Australians.

In January 1943, the Centaur was converted into a hospital ship, and on May 12, it left Sydney to transport the 2/12th Field Ambulance to New Guinea.

Her hospital status was obvious. The Centaur was painted a brilliant white with a broad green stripe around her hull, and she was marked with large red crosses.

But at 4.10 on the morning of May 14, just before dawn, a single torpedo exploded against the ship’s fuel supplies. She sank within three minutes.

Seaman Matty Morris, 22, from Melbourne, had just finished his watch duty when the torpedo hit.

“I was just havin’ a cup of tea,” he recalled, “and (there was) this big explosion, and the ship gave a shudder, and the skylight fell in on us. I was washed off the back of the ship and then I realised I was in the water.”

Ellen Savage was asleep in her bunk when the 96m, 3200-tonne vessel began to fold in around her.

“Merle Morton and myself were awakened by two terrific explosions and practically thrown out of bed,” she remembered. “In that instant, the ship was in flames. We ran into Colonel Manson, our commanding officer, in full dress, even to his cap and ‘Mae West’ lifejacket, who kindly said, ‘That’s right girlies, jump for it now’.”

Nakagawa was never convicted for the crime, but he did serve six years in a Tokyo prison as a war criminal for ordering the machine gunning of British sailors as they bobbed helpless in the Indian Ocean after his sub sank the oil tanker SS Chivalry near the Maldives a year after the Centaur went down.

Matty Morris found himself alone in the cold, dark water, his eyes full of salt and oil. He spotted a small raft and then saw his mate, Bobbie Teenie, and hauled him aboard. In their loneliness and fear, they hugged each other, even as the raft began to sink.

The light began to shine over the horizon and they saw a bigger raft in the distance. Sister Savage was already on board.

During the next 34 hours, other survivors, including 20-year-old Martin Pash from Melbourne, made their way to the bigger raft.

Sharks circled.

Morris encouraged the survivors not to give in to fear. He organised a one-shilling sweepstake among the 10 desperate men on the raft, guessing when they would be rescued, and he led them in vigorous renditions of Waltzing Matilda.

Morris was pressed up against badly burned private Jack Walder, 22, from Orange in NSW, who remained silent.

“He died next to me, and his burns just stuck on my arm,” Morris said later.

“I said to Sister Savage, who was practically opposite me, ‘I think this young chap’s dead’. And she said, ‘Are you sure?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m pretty sure’. As she felt over, she said, ‘He’s passed on’. So I took his identification disc off him. I gave his identification disc to Sister Savage. She said the rosary and I answered it, and we buried him at sea.”

At the time, Jack Keith was a 20-year-old Flight Lieutenant on board an Avro Anson that was flying patrol at about 300m off the Queensland coast, doing an anti-submarine sweep with no idea the Centaur had been hit.

“As we then turned back towards the convoy, we saw a discolouration in the water well to the south, so we turned back for a look,” Keith told RAAF historian George Hatchman.

Keith saw a raft and people in the water, and a white sign with one word painted in black: Centaur.

“As soon as we saw it was the Centaur, a hospital ship, we thought, ‘Well, flaming Charlie, things are a bit rough – they shouldn’t do such things’.

“If we hadn’t seen them, I don’t think there would have been a future for them because the convoy had gone out, and there wouldn’t have been any other ships around there for seven days.”

Morris seemed happier than any of the other survivors as the Anson circled. He won the sweepstake, guessing the rescue time within half an hour.

On December 20, 2009, after a campaign by The Courier-Mail raised $4 million, UK-based shipwreck hunter David Mearns, who had previously found the wrecks of the Sydney and the Kormoran off the West Australian coast, discovered Centaur’s wreck about 55km off the southern tip of Moreton Island.

It was lying more than 2km below the ocean’s surface.

Martin Pash, the last survivor, died in a Melbourne nursing home in 2012 aged 92, but he lived long enough to attend a 2010 memorial service at the site of the disaster after a navy transport ship took mourners to the wreck site.

Photographs of the wreckage show the red crosses marking her as a hospital ship are still vivid against the white hull.

Immediately following the sinking, the US’s General Douglas MacArthur, supervising the war in the Pacific from his headquarters in Brisbane, told The Courier-Mail: “I cannot express the revulsion I feel at this unnecessary act of cruelty. The enemy does not understand – he apparently cannot understand – that our invincible strength is not so much of the body as it is of the soul, and it rises with adversity.”

Sister Savage was subsequently presented with the George Medal for her heroism in saving others.

At the Greenslopes Hospital where Ellen and other survivors were treated, crewman Alex Cochrane, of Perth, told The Courier-Mail she had kept the spirits of the survivors afloat with prayers for deliverance.

“She was wonderful,” he said. “She never once complained. When she said to someone, ‘please don’t lean on my side’, we thought she was just tired. It turned out later that she had two broken ribs.”

Sister Savage cried only once during the ordeal – when the rescue plane signalled that it had seen them.