50 years after Brisbane’s trams were scrapped, it’s not too late to fix this this epic planning fail

Fifty years on, the scrapping of Brisbane’s trams remains one of the most appalling urban planning mistakes in the city’s history and only now are planners looking at righting a monumentally stupid wrong, writes Michael Madigan.

CM Insight

Don't miss out on the headlines from CM Insight. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT WAS one of the most appalling urban planning mistakes of the 20th century yet, today, as we mark the 50th anniversary of Brisbane’s last tram service, there’s reason for optimism as urban planners set about trying to right this historical wrong.

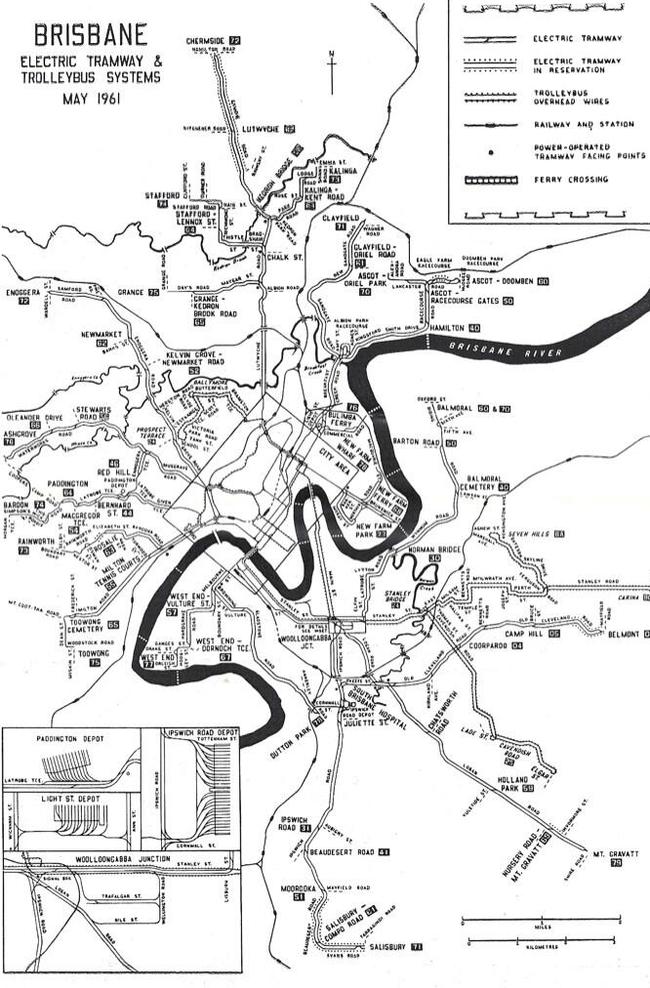

Those humble trams which trundled their way through Brisbane’s city and surrounding suburbs from June 21, 1897, until April 13, 1969, are still the perfect panacea to urban congestion.

Yet, ironically enough, it was urban congestion which prompted their demise.

Emeritus Professor Peter Spearritt from UQ’s School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry and an expert in urbanisation, sees the removal of trams in the post war years as an urban planning catastrophe which swept the developed world.

In Australia, only Melbourne sidestepped the disaster, remaining the only English speaking capital city to retain a fully functioning tram system.

And the reason why countries from New Zealand to Ireland to the great cities of Europe banished trams?

“To avoid traffic congestion,” laughs Spearritt, semi-retired but still a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia and co-editor of five major public websites dealing with history and economics.

“That is the truth – they all thought if they cleaned out the trams, that would allow the new modern motor car to move easily through their cities.”

Trams still have sentimental value among ageing Queenslanders who remember being spirited swiftly from suburban homes into downtown Brisbane to go shopping with their mum and dad.

But, as Spearritt says, their practical value far outweighs their nostalgic value, and as the 21st century unfolds, more and more communities will see the value in going back to the future, and bringing back the tram.

IT WAS the global obsession with the motor car – combined with the almost euphoric economic optimism that swept through the world in the 50s and 60s – that swept trams aside.

The tram, in the eyes of many, ceased to be viewed as an essential feature of an urban landscape and came to represent a relic of a shabby, industrial past.

In London, even the august publication The Economist loudly crowed its support when London began dismantling its tram system in the decade after the war.

The magazine, at the forefront of economic trends since it was founded in 1843 to advocate for the repeal of the Corn Laws, saw the car as the symbol of the “new economy”, the tram a relic of the old.

Its journalists advocated the public get onto a car or one of the slick new Leyland buses that Leyland Motors (later British Leyland) were churning out and which eventually found their way to Brisbane in the 60s.

In Brisbane, many rightly point the finger at the legendary mayor Clem Jones as the villain who dispatched the Brisbane tram to history as he became enamoured with the shiny new Fords and Holdens rolling off Australian assembly lines.

Jones was further inspired in his enthusiasm for cars by a visit to Brisbane by American urban planner, Wilbur Smith, whose country had embraced the car and changed their landscape with motels and freeways to accommodate it.

Smith, who advocated and oversaw the building of roads and underground carparks in cities to cater for increases in population, wrote a report advocating that Brisbane do the same and rid itself of trams and trolley buses.

ON SEPTEMBER 28, 1962, when a massive fire at the Paddington tram depot destroyed a fifth of the city’s tram fleet, legend has it that Jones declared “let it burn”. That legend has been enhanced and embellished over the years to put Jones centre stage as the arsonist who lit the fire himself so he could wipe out the tram fleet. This was, of course, all urban myth, and to the overwhelming majority of Brisbane residents who remember Jones, his lifelong commitment to public service and building a better Brisbane effortlessly eclipses the mistakes (easily identifiable in hindsight) he might have made regarding trams.

But Spearritt does acknowledge it was the vision of the ever-optimistic Jones, combined with a few other factors, which led to the demise of Brisbane’s tram system which formally ended when the last service made its way from Balmoral to Ascot on April 13, 1969.

Jones’ futuristic visions, the ever growing power of the motoring lobby under the RACQ, and the decision by then prime minister John Curtin’s government in the midst of World War II to rob state governments of the power to impose income tax, all conspired to consign the tram to history.

“Canberra had got control of income tax off the state during the war and Canberra, under the influence of the motoring lobby, began spending big on the nation’s road system after the war,” Spearritt says.

WHILE THE car appears to have always been with us, millions of Australians could only dream of one even up to and including the war years.

The first Holden, made in a collaboration between Holden and the US General Motors, rolled off the assembly line in 1948. But it was the decision by the new conservative government under Bob Menzies in 1949 to end petrol rationing which spurred on Australians to buy one.

Melbourne held onto its trams only because it had a powerful, independent statutory body running them (the Melbourne and Metropolitan Tramways Board, which merged into the Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1983).

Melbourne also had a series of wide, European-inspired boulevards where trams could keep their own territory and not compete for space with other traffic, while in cities such as Sydney and Brisbane, roads were merely an enhanced and paved system of tracks hacked out by convicts.

Yet Spearritt insists all is not lost. The opening of the Helensvale to Southport light rail project a year ago is one of those green shoots of urban development that point to a more positive approach to planning, he says.

Hundreds of kilometres of Brisbane bus lanes, he says, are also perfectly situated to be transformed back into tram lines, all free of interference with motorised traffic competing for space.

Says Spearritt, “Light rail just makes sense for our cities, and I think that planners are beginning to recognise that.’’

Attend a commemoration day at Tramway St, Ferny Grove, today. brisbanetramwaymuseum.org