Indigenous leader Uncle Wayne Fossey explains what people are getting wrong about Welcome to Country

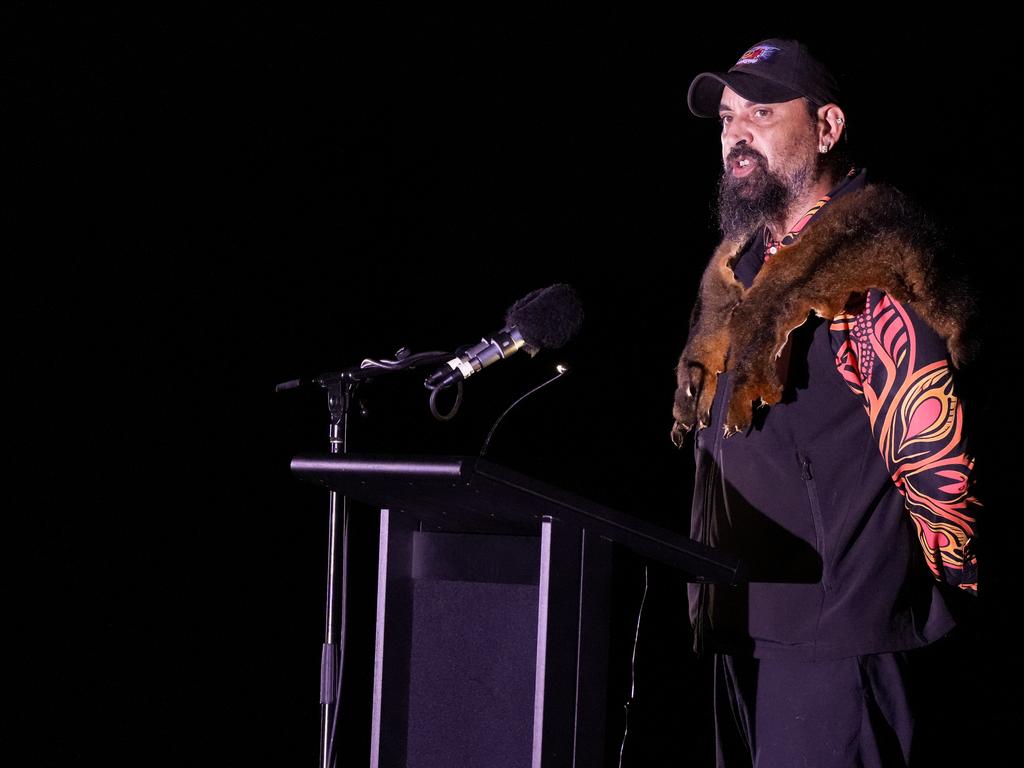

Darling Downs Indigenous leader Uncle Wayne Fossey, whose father and uncles fought in World War II, has condemned the booing during Anzac Day’s Welcome to Country and explained the importance of the ceremony.

As the sun rose over Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance on Friday’s Anzac Day, Bunurong Elder Uncle Mark Brown began a Welcome to Country.

On the dawn of one of Australia’s most important days which honours servicemen and women, more than 3500 of which were Indigenous who fought to protect this country, a small group of neo-Nazis began to boo.

The jeers were quickly drowned out by cheers from the crowd, but the vile act on such a sacred day has left a sour taste in the mouths of many.

Despite the appalling outburst many on social media have sided with the hecklers and called for an end to the Welcome to Country.

A recent news.com.au poll with 50,000 responses showed two thirds of people were in favour of scrapping Welcome to Countries with the most common response being “why do I need to be welcomed to my own country?”

“Why do I need to be welcomed to my own country?”

For Darling Downs Indigenous leader Uncle Wayne Fossey, whose father and uncles fought in World War II, the interruption was tragic.

“A lot of people say how can you welcome me to the country I live on, but we all live on the same country, we share the resources and we should share the history and cultural values,” he said.

“I think people feel uncomfortable like ‘this is our country and we pay rates’, but that doesn’t mean you own the land, it means you have a legal ownership to the Crown.

“It gets confusing, I think the word ownership is a part of it so I prefer to use the word custodian. We don’t really own it because the land owns us and you only need a storm or cyclone to remind you of that.

“I look at people like my dad who went away with his brothers to World War II and were fighting for Australia.

“He wouldn’t have wanted to change the flag to an Aboriginal flag, he would’ve wanted an understanding where everyone worked together.

“I said to my dad once ‘why did you go to war?’ And he told me ‘I went to war because I wanted to protect this country’.

Uncle Wayne said while the modern Welcome to Country ceremony was created in 1976 the tradition of welcoming people to country dated back thousands of years.

“A welcome to country is a traditional welcome,” he said.

“Say you are going to the Bunya Festival, people would walk from Sydney and they would be invited by message sticks. You would get to a certain point of country and you didn’t want to invade so you’d sit and have a gathering.

“The people that lived there would decide can we feed these people, are they going to respect us, can we trust them? The second component of the welcome is the idea that we will take care of you and protect you while you are on the country.

“It is about sharing your resources, sharing your environment and being protected, if there was an attack on that group then you would defend the group that came as your visitors.

“You would also have a big party to welcome them in and the concept is around food and celebration.

“It’s a positive concept that has been lost in time and one that many people get wrong”

Why is the Haka accepted but Welcome to Country condemned?

Looking to our neighbours in New Zealand it is hard not to draw parallels to the Maori and their Haka, which much like the Welcome to Country represents strength and unity.

Considered a source of pride for both Maori and non-Maori people, the Haka is beloved and performed before rugby games and cultural ceremonies.

So this begs the question why is it that the Haka is celebrated but the Welcome to Country is condemned?

Uncle Wayne believes this is due to Australian being years behind New Zealand in both cultural acceptance and education.

“I think we are a long way behind New Zealand in terms of the visibility of Aboriginal people, we don’t have the numbers, the show or the display,” he said.

“We don’t have the education at school, it was never taught to me, for us as kids our language was always kept silent.

“The other significant factor is there isn’t just one Aboriginal population, there are thousands of language groups and the groups themselves haven’t communicated those messages over time.”

What is ‘country’?

Uncle Wayne said to Indigenous people ‘country’ was more than just Australia the country, but rather an abstract concept.

“Country is a spiritual and cultural relationship, it includes land, water and sky and the idea of all of these forces of nature coming together,” he said.

“People have this concept in their brain that land equals the physical thing you walk on but it is beyond that, people think of it as a boundary with a fence, if you look at Native American culture there is similar issues of who owns the fence.

“There should be no fences in our brain when it comes to understanding country.

“Country is something that lives within you, yet people still think of it as real estate.”

Uncle Wayne asked those with trepidation surrounding the Welcome to Country to go out and talk with an Aboriginal person.

“I think greeting someone is important in any culture or language, I don’t see a problem with the word ‘welcome’ or jingeri as we say in our language,” he said.

The whole saying is jingeri warloo which translates to ‘welcome everyone’, no one is excluded.

“We need to get more people to meet Aboriginal people, shake their hand and go on country.

“We need an emphasis on listening to people and reading up on these things, what we believe is if you don’t understand or care for country the world will not heal.”

Originally published as Indigenous leader Uncle Wayne Fossey explains what people are getting wrong about Welcome to Country