Shelley Conway shares grooming tale to boost Bravehearts campaign

A Gold Coast mum has a warning for parents – a warning about the disturbing behaviour of predators, and how they can betray a family’s trust. This is her story.

Gold Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Gold Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Shelley Conway knew she was his favourite.

She was the one whose opinion he sought, she was the one who received special gifts, she was the one he made feel important.

She was the one he picked out with his wandering fingers. She was the one he abused.

And while he was the one who groomed her, society made it all the easier.

Taught to smile, to be polite and respectful to adults, to hug and kiss her elders, Shelley was trained to stay compliant … and silent. But she also made the perfect target because she was already vulnerable. Because even at the age of seven, she was already a victim-survivor.

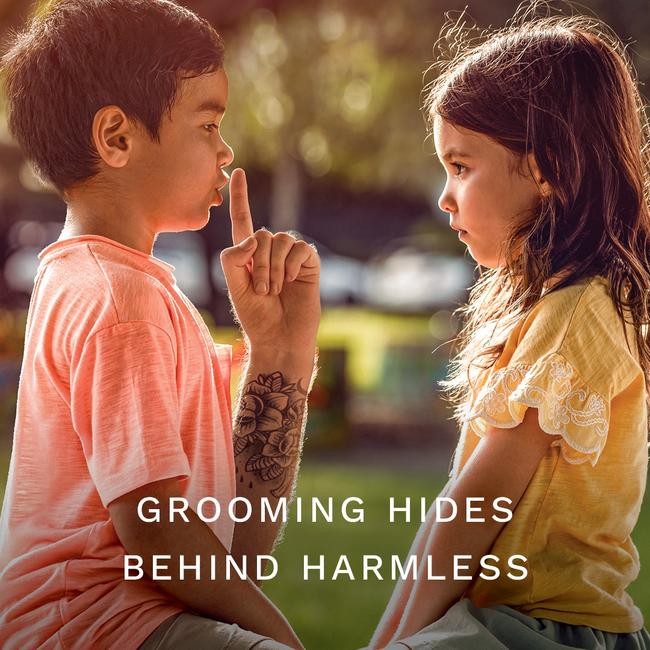

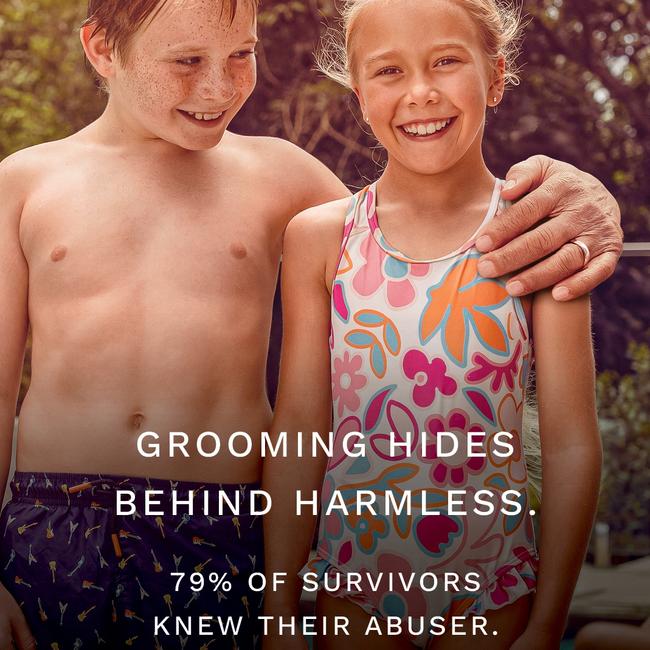

Now in her 40s with her own children, Shelley said she was sharing her story to amplify the new campaign by not-for-profit child protection organisation Bravehearts to help parents recognise and prevent grooming, a danger she knew all too well.

Bravehearts research showed that more than one in four Australians had experienced child sexual abuse and in 79 per cent of cases, the perpetrator was someone the child knew.

Indeed, Shelley said while it takes a village to raise a child, parents needed to know exactly who was in their child’s village.

“It didn’t happen to me just once, and each time it was not a stranger. No one snatched me off the streets in a white van, it was someone who had access to my home,” said Shelley, an artist who was born and raised on the Tweed and Gold Coasts.

“Perpetrators don’t find opportunities, they create them.

“The first time I was only five years old and there was a party and one of the ‘guests’ was so inebriated that he was annoying everyone at the party, nobody wanted to be around him.

“It was suggested by someone there that I take him to see our rescue pet possum in the laundry and I’m sure in my five-year-old head I was like, why me?

“But I just obliged and walked him down the hall and all I remember now when I think back is me just walking down that hall.

“We went into the laundry and he closed the door because you couldn’t let the possum out. I was telling him about Rastus, the possum, and then I turned around and he’d unzipped his pants.

“I don’t know how much detail to give but I’m so mindful that you can tell a story as a warning and someone could read it and get off on it. It makes me feel sick just thinking about that.

“I was so innocent, I didn’t even know how babies were made or anything about sex. Sexual acts occurred but I didn’t even have the name for them. It’s left me with so many triggers.

“It felt like it went forever. I remember just sitting there wishing that someone would rescue me. That someone would just find me or wonder where I was and why I had been gone so long.

“Finally there was a knock on the door and he stopped. I just remember he was so tall and I was just five and he’s looking down at me and swearing me to silence and that if I say anything, he’ll kill someone in my family.

“Still, to this day, I just don’t even know how that was able to happen with so many people around.”

Shelley said the lack of societal awareness about child sexual abuse was part of the reason her perpetrator was able to act so boldly.

She said culturally acceptable behaviours helped grooming to occur, but said not as much had changed as needed.

“As a child, we were always taught ‘don’t be cheeky’ and respect your elders, but that just encourages silence,” she said.

“The only warning we heard as kids was the whole ‘Stranger Danger’ thing from school. But no one spoke about child sexual abuse.

“My family loves music and there was always a guitar and microphone going around and I remember my sister and I, when we were about six and 11, they would always get us to sing ‘We Wear Short Shorts’.

“We thought it was a catchy but lame song but knew everyone loved it, and nobody had any deeper meaning in getting us to sing it, but that’s really not an appropriate song for kids to sing. It is sexualising kids.

“There’s no way in hell I would ever get my kids up to do something like that.

“Even now, I hate to see little kids in pageants or even in some singing or dance contests with the costumes and make-up where we’re ageing them up, it does make me feel a bit sick.”

Shelley said her personal experiences meant it was even easier for the next perpetrator to groom her.

She said the childhood trauma made her both vulnerable and extremely sensitive about seeming too ‘emotional’, with her family confused about why would cry often or become easily upset.

“But I had no language to explain what had happened to me. And being the one who feels different, that makes you more vulnerable to a predator – they pick off the young, the shy, the one who might not fit in,” she said.

“When I was seven and then again when I was 12, the same person targeted me.

“I had so little defence. Even what we were made to wear back then, school ‘bloomers’, they made it easy for wandering fingers to find you.

“This person would try to make me feel special, he would ask my opinion on things, buy me little gifts as a reward, make me feel important and valued … but there was a price.

“When I was seven, I was so confused about what was normal and when I was 12, I knew it wasn’t right but I didn’t say anything because I didn’t know if it was my fault.

“Of course it wasn’t, I know that as a woman in my 40s, but as a child I didn’t.”

Now, as a parent, Shelley said the best thing anyone could do to protect their child was to build a close relationship.

She said no amount of helicopter parenting could protect them, but building trust between parent and child was essential, as was being aware that the most likely danger would come from someone the child knew.

“It takes a village to raise a child, but you need to know who is in your village,” she said.

“You can never monitor every space 100 per cent, you can never be completely vigilant, but you can educate yourself to really vet who is in your circle, but you also need to arm your child.

“Your child needs to know how to be autonomous, how to make decisions and be confident so they can be brave and stand up for themselves when they need to.

“Sitting down with your children and actually talking with them frankly about these dangers and always being open and honest with them, building trust and removing shame, this is how you empower them.

“Let them make decisions, within reason, don’t force them to kiss relatives, don’t force them to wear what you want them to wear, let them know they have a voice and they can use it.

“Teach them to trust their gut and that if they feel uncomfortable, it is far better to offend someone than to get hurt.

“I’ve always been very candid with my children that I am a survivor of child sexual abuse. That has taught them empathy and it has taught them that there is no shame, and that if anything happens, they know I will understand. They’re proud of me.”

Shelley said it was important not just for parents but educators and the public to understand what grooming looks like and the effect that trauma can have on a person.

She said she was still learning about her own recovery and increasing awareness around child sexual abuse as well as complex PTSD had helped in her journey.

“It’s important to know what trauma can look like, it’s not always rocking in a corner, it can be hard to pick,” she said.

“The emphasis for parents and teachers should be about learning to listen to our kids, we need to be able to hear when something is off, and learn how to empower them to talk to us.

“For me, my family and my art and working with Bravehearts, to have a platform for my voice and to realise that it has an impact, has been incredible.

“A part of me always feels like that little girl walking down that hallway, but now I can finally see an end.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Shelley Conway shares grooming tale to boost Bravehearts campaign