Cunningham: Trump’s victory shows how progressive politics is in crisis

There’s a growing and increasingly diverse group of voters realising this new brand of progressivism is leaving them behind.Left-leaning parties sit at a crossroad. Do they learn the lesson from Trump’s re-election? Or do they continue to look down on those who voted for him, writes Matt Cunningham.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Progressive politics is in crisis.

Elections in the Northern Territory, Queensland, and now the United States have seen the policies of Labor and the Democrats roundly rejected.

There are different reasons in different places for the victories of conservative parties – crime in the NT and Queensland, immigration in the US – but there is a common theme that a growing number of younger, predominantly male, working-class voters are rejecting a new brand of progressivism that has comprehensively rejected them.

Rejected them so badly, in fact, that they were happy to vote for a narcissistic lunatic and convicted felon.

Former Labor strategist turned Redbridge pollster Kos Samaras – who accurately predicted the CLP’s landslide NT victory more than nine months out from the election – says Donald Trump’s victory “revealed a deepening divide between traditional working-class voters and the established left-leaning parties”, a trend he says is “reshaping politics across the Western world, including in Australia”.

“The Queensland state election underscored a growing separation between urban progressives and the working poor in regional areas,” Samaras told Neos Kosmos.

“Traditional Labor-aligned parties are now drawing support largely from university-educated professionals while leaving regional and working-class voters feeling neglected and unheard.”

Blue collar workers were once Labor and the Democrats’ bread and butter.

But the shifting sands of western politics, including here in Australia, are leaving them behind. Here, the party that gave the working poor free university education under Whitlam and well-paid jobs with good conditions under Hawke and Keating is today drawn into the first-world concerns of wealthy inner-city professionals as it fights with the Greens for their votes.

In the United States, the Democrats have been busy winning the endorsements of billionaire celebrities while Trump was promising blue-collar workers he would bring back their manufacturing jobs.

In Australia, there are plenty of examples of Labor deserting its former base to win favour with its new friends.

Here in the Territory, large parts of the Labor Party are opposed to fracking, an industry with the potential to provide thousands of well-paid blue-collar jobs.

Despite the dodgy polling sometimes rolled out from environmental groups, access to a good job rates far higher than concerns about climate change, especially in a cost-of-living crisis. Territory Labor might consider the lesson from the United States where Trump just won an emphatic victory with a resources policy that was one, simple, three-word statement: “Drill baby, drill.”

More concerning, however, is the way progressive politics is reframing disadvantage to suit its new supporter base.

Disadvantage was once a concept based on class, with left-wing parties focused on getting a better deal for those worse off.

But today’s society has substituted personal attributes such as gender, sexuality and race as proxies for disadvantage, often leaving the battlers behind.

As David Brooks noted in the New York Times this week: “I guess it’s hard to focus on class inequality when you went to a college with a multi-billion dollar endowment and do environmental greenwashing and diversity seminars for a major corporation.”

The reframing of disadvantage is a trend born in America that is taking a strong hold here. Take, for example, the Northern Territory’s Special Measures policy, which gives priority to Aboriginal candidates in public service jobs if they meet the selection criteria, but makes no assessment on the geographical or socio-economic background of those candidates.

This has been a big win for interstate applicants with university degrees who identify as Indigenous, but has done little to improve the bleak employment prospects of Aboriginal people in remote parts of the NT.

At a federal level, the government considers indigeneity when assessing the distribution of GST funds between the states and territories, but, as the Yothu Yindi Foundation has previously pointed out, makes no distinction between a university-educated couple living in Parramatta, and couple living in a humpy in Papunya.

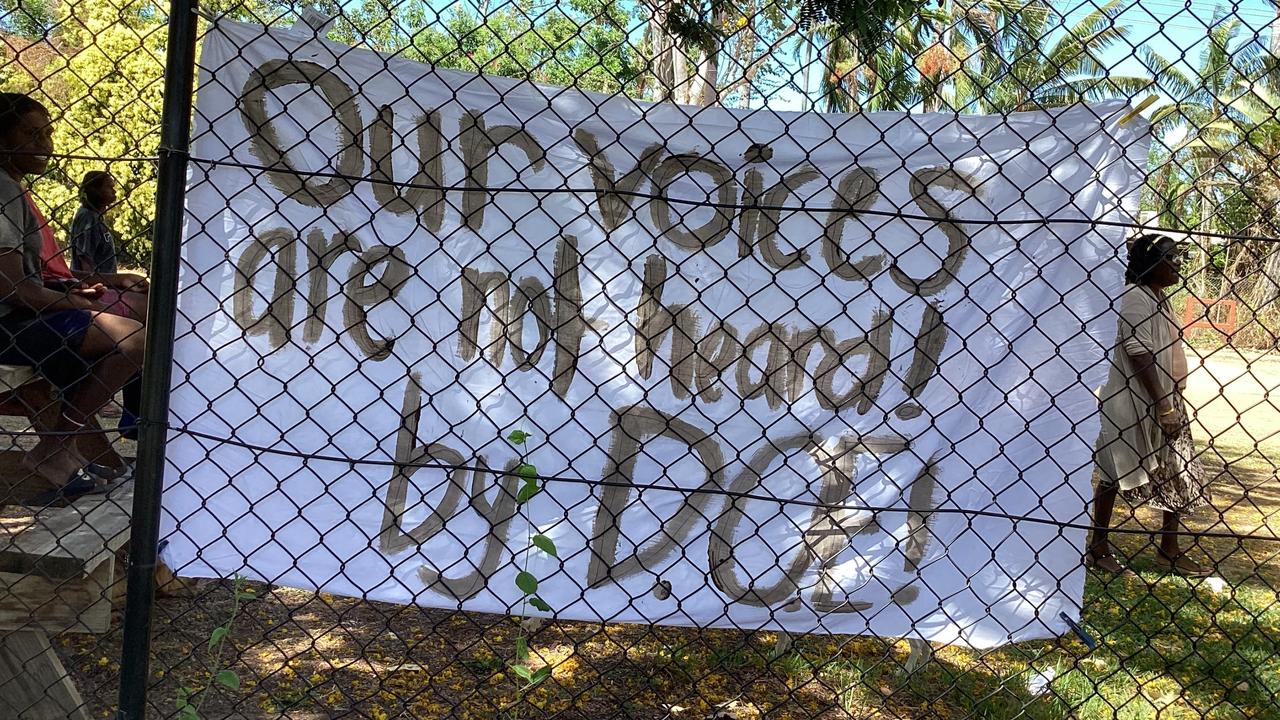

Meanwhile, Canberra just spent $411 million on the failed Voice referendum while continuing to ignore the woeful infrastructure deficit it left the Northern Territory’s remote communities almost 50 years ago, that continues to contribute to shocking health, education and employment outcomes for Australia’s most disadvantaged people.

It’s worth noting here that Trump’s victory came not just on the back of the white working class but was also aided by a significant increase in black and Hispanic voters.

There’s a growing and increasingly diverse group of voters realising this new brand of progressivism is leaving them behind.

Left-leaning parties now sit an important crossroad. Do they learn the lesson from Trump’s re-election?

Or do they continue to look down on those who voted for him, mocking them as garbage or deplorables, even as their numbers grow in a world that is increasingly leaving them behind.

Originally published as Cunningham: Trump’s victory shows how progressive politics is in crisis