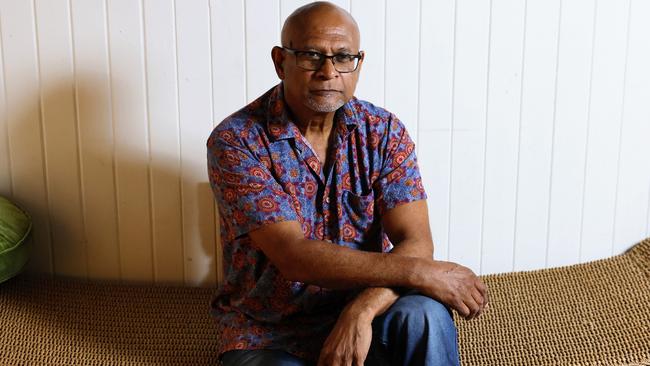

Rheumatic heart disease won’t stop ravaging remote communities without collaborative approach, says Dr Mark Wenitong

A leader in First Nations healthcare says the current approach to solving health issues is not working and believes a Voice to Parliament could be the answer.

Cairns

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cairns. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A leader in First Nations healthcare says the current approach to solving health issues is not working and believes a Voice to Parliament could be the answer.

Dr Mark Wenitong, who co chairs the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Clinical Network, said health issues in Indigenous communities were influenced by social factors, requiring an approach that took into consideration all issues affecting their lifestyle.

“I say rheumatic heart disease is also a problem with housing and when I ask why housing isn’t here, though they work right across the corridor, I’m told that’s housing, not health,” he said.

“You can give my organisation as much money as you want for rheumatic heart disease forever, it will make no difference.

“We will diagnose it and treat that, but a third world disease will still be prevalent in our communities unless we sign up on a remote housing agreement.”

In a similar vein, electronic medical records meant nothing if there was no consistency in telecommunications connectivity.

Working locally and regionally in Cape York, the biggest problem in Dr Wenitong’s experience was getting everyone in the same room.

“Education department, communities, Feds, we are all interacting but the problem is there is no macro policy that mandates that everyone has to sit in a room so they don’t and we end up not having a coherent response,” he said.

The idea that some sort of Voice already exists was not true, he said, stating taskforces and committees were essentially a response to the government’s wants and needs at the time.

“The only voice we have kind of had in some ways has been big consultancy groups coming out, consulting with our communities, then going back to government and telling them what we said for $500,000 when you could’ve just paid uncle Charlie $50 and he would have told you the same stuff directly but not as polished.”

Consultations were not like research which needed to be peer reviewed and was owned and paid for by the government, he said, meaning it had to be palatable to the policy consistency of the government of the day.

“A Voice embedded in constitution is structurally different – it means we don’t care who is in government you’re just going to have to listen to us one way or another.

“You can reject it but don’t say we didn’t tell you or give you the right advice,” he said.

A recent example of this in action was with a national Indigenous Covid taskforce, Dr Wenitong said, where the government “actually listened”, and this helped target the communities likely to be hit the worst and arrest the spread of disease.

“It was community controlled mostly, and our own public health experts, most of the information came from our communities directly and it was widely successful.”

It couldn’t be sustained after 18 months due to lack of infrastructure but the structure proved the call for a front end Voice that was not just response-driven “had legs”.

Dr Wenitong was among the first Aboriginal medical graduates in Australia and is currently one of the national mental health commissioners on the National Mental Health Commission, and director of research translation at the Lowitja Institute.

More Coverage

Originally published as Rheumatic heart disease won’t stop ravaging remote communities without collaborative approach, says Dr Mark Wenitong