‘Torture’: Australian journalist Cheng Lei’s three years of hell in Chinese detention on bogus espionage charges

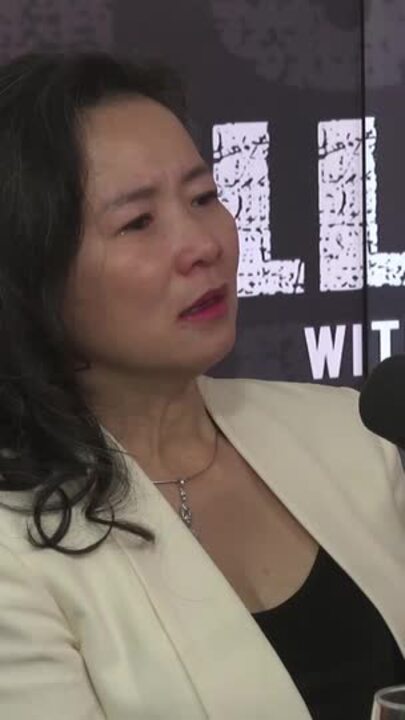

An Aussie TV news anchor who spent three years locked up in China on bogus charges has revealed the disturbing torture techniques officials used to break her.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When a Chinese court handed Cheng Lei a prison sentence for trumped-up espionage charges, she quietly calculated how old her two young children would be when she saw them again.

Teenagers, she realised, in a harrowing moment that almost broke the Australian’s will.

“My kids were very painful to think about,” Cheng recalled. “I didn’t know if I’d ever see them again. But ultimately, I knew I had to be strong and sane to be able to look after them if I got out.”

Cheng, now 49, spent more than three years cut off from the outside world in detention in Beijing, subjected to horrific mental torture after falling foul of the Communist Party.

Her crime? Discussing a government press release with a fellow journalist several minutes ahead of a supposed embargo.

Why China went after the respected broadcaster, who was the face of the country’s CGTN news channel and anchor of its most popular program, is still a mystery.

But her arrest and imprisonment coincided with a deep erosion of diplomatic and trade relations between Beijing and Canberra, leading many to conclude she was a pawn in a merciless political game.

Almost five years on, she still bears the deep scars of her barbaric treatment.

Relentless mental torture

In August 2020, Cheng was greeted at work by some 20 officials from the secretive Ministry of State Security.

“I am informing you on behalf of the Beijing State Security Bureau that you are being investigated for supplying state secrets to foreign organisations,” one told her.

A few months earlier, Cheng had received a press release about the Premier’s Work Report, the main document to come out of the Communist Party’s largest political gathering of the year.

She was sitting in a make-up chair, getting ready to go on air, and texted a colleague a brief summary of the highlights – eight million jobs target, no GDP growth target – to help them get a headstart on a story.

“And that was my crime, that I eroded the Chinese state authority, even though there wasn’t an embargo [on the report],” Cheng recalled.

Much later, in court, another colleague who she barely knew testified against her – likely under coercion – and claimed she’d told Cheng there was in fact a strict embargo.

“That is bogus,” she said.

“If I had known it was a classified document embargoed before 7.30, why would I send it to my friend, and then keep the document, keep the texts?”

Cheng was taken from her office to her apartment and watched on as spies ransacked it, looking for evidence that didn’t exist.

Then she was blindfolded, bundled into a blacked-out SUV and whisked to an RSDL facility, or Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location.

There, in a small room that was brightly lit around the clock, she was forced to sit perfectly still for 13 hours a day, every single day, for several months.

On either side of her were two heavily armed guards and she couldn’t so much as scratch her cheek or adjust her posture.

“I wouldn’t send my worst enemy there,” Cheng said.

“Sure, I wasn’t cold, I wasn’t starving, but it’s mental torture. And that is something that is very Chinese, trying to break your mind … that constant pressure, dehumanising you.

“You are nothing, you cannot say a thing, you cannot make a move without their permission. And you see no one, you see nothing. It makes your brain go dead. And that is what they want. They want you desperate.”

For months, she was interrogated relentlessly as the Ministry of State Security tried to justify its trumped-up charges.

Had she been secretly helping Uyghurs, a persecuted minority in China? Was she trying to infiltrate the Foreign Ministry? Was she receiving suspicious sums of money?

Every bogus avenue the government explored was a dead-end.

The pain of the unknown

She was totally isolated from the outside world and only permitted a brief 30-minute video conversation with Australian diplomatic officials once per month.

Five Chinese guards would crowd closely around her during those meetings to make sure Cheng didn’t say anything problematic about her treatment.

“Even when the embassy officials asked how many interrogations I’d had, when I tried to reply, they would say, no, cut. And their rule is, if you say anything that you’re not allowed to say, then the visit gets cancelled, and you might lose visits altogether.”

Outside of those 13 hours of forced sitting, Cheng was monitored every other moment of the day, including when using the toilet and while sleeping.

She tried to picture the happy times with her family. She imagined them playing on a beach or eating dinner together, clinging to hope that they would one day be reunited.

A doctor would visit each day to take her blood pressure, and during one check-up, Cheng noticed he was wearing new sneakers.

“It was the first beautiful thing I’d seen in weeks. And I said, I like your shoes, even though I’m not supposed to make small talk. And he said, thank you.

“And even an exchange like that, I would just keep replaying it and remind myself of it.”

After six months, she was pressured to confess to the manufactured charges or face a more severe punishment at the end of a trial.

Reluctantly, she did, knowing her fate was inevitable. No-one is found innocent in China’s justice system.

“I worked out what ages my kids would be by the time I got out,” she recalled. “It was horrible. But had I not pleaded guilty, my sentence would have been a lot longer and my treatment would have been a lot worse.

“What is the point of a defence lawyer? There’s only the state. The state is the only thing that matters.

“And at least in jail, I could see a bit of the sky.”

A star sacrificed

Cheng was working as an accountant in China “right on the cusp of its globalisation” when demand boomed for English reporting on the country’s expanding economy.

Having felt like a corporate zombie and wanting a change, she made the leap to television journalism.

“I knew nothing about TV or even much about journalism, except that I liked it, and it was a steep but pleasurable learning curve,” she recalled.

“And I was super happy when I got the call from CNBC, a year-and-a-half after I got into the business, that they wanted me to be their China correspondent.”

For nine years, Cheng brought viewers the latest news about China’s roaring economy and increasing global dominance.

When she left CNBC, she became the face of CGTN in China, anchoring its major news program and rising to become a star of the industry.

She loved her job, but it came with its challenges in a country where information is tightly controlled by an army of censors and propaganda-pushers.

“Once, we interviewed the head of China’s top brokerage and I asked a question that he didn’t like, that he deemed derogatory to the Communist Party. He ordered his people to not let us go and seized our camera and said we had to delete the footage.

“There were some frantic negotiations and eventually we got out, but they wouldn’t let us play the interview with that question in there.”

Those handful of run-ins aside, Cheng felt relatively self. After all, she was reporting on business and finance – not politics or international affairs.

But as Beijing’s thirst for power grew, the line between the corporate world and the Communist Party became worryingly blurred.

In the early part of the Covid outbreak, Cheng’s pursuit of a new show format saw the two become intertwined.

“The Covid eruption meant that my kids couldn’t come back from their holiday in Australia. I was at a loss because I’d been a working mum all this time, and I was adept at juggling work and motherhood, and I really loved bringing up little people.

“So, I tried to channel my extra energy into other things, like an idea for another show. It was about dining and cooking with ambassadors. I thought it’d be a nice way to bring international flavours to viewers.

“It meant going to a lot of embassies, speaking to a lot of ambassadors. Now that I know the Chinese mindset – I mean, recently at a trial, a court declared all diplomats in the Japanese embassies are spies, fair dinkum – now that I know the way they think, my activities must’ve been extremely suspicious to them.”

But Cheng felt like her career was at its peak. She was successful, popular and extremely well-regarded in the corporate world.

Even as colleagues began quietly talking about their experiences of being surveilled or questioned by officers from the Ministry of State Security, there didn’t seem to be cause for alarm.

When she was detained, the accusation was so crazy that Cheng was sure it would all be sorted out swiftly.

“The idiot that I was, I thought I’d be back in a few days. I was thinking, this is just a big mix-up. I can explain it. I’ve done nothing wrong.”

Freedom, finally

In all, Cheng spent three years in detention before eventually being freed in October 2023 after a long-running public campaign tirelessly fought by her peers and friends, and the diplomatic efforts of the Australian Government.

Had that fight failed, she would still be behind bars until November.

When she left the detention centre, she was taken to a halfway house and for the first time years, she was able to enjoy what she describes as being a host of “luxuries” like a mirror, a sit-down toilet, and a string to hang her washing on.

The moment her plane home to Australia left the ground, a sense of total relief washed over Cheng.

“For once I could say anything. The embassy had given me a phone, but I just looked at it and I thought, I’m surrounded by people, I want to see and touch and talk to every one of them. What am I going to do with a phone?

“For years, I could only talk to a few people. Now I’m free to express again. To be able to speak English, to use my name, because all that time I was just known by my number, 21003.”

Back on Australian soil, the experience of seeing her kids again after so long was “euphoric” but also bittersweet.

They had grown up so much in her absence.

“I think both were trying to impress me. My son wore his favourite Barcelona jersey, and my daughter wore her school uniform because she loves her school.

“But they weren’t little kids anymore. I’d missed all that. They had to go without mum for all that time, not sure when I’d be back.”

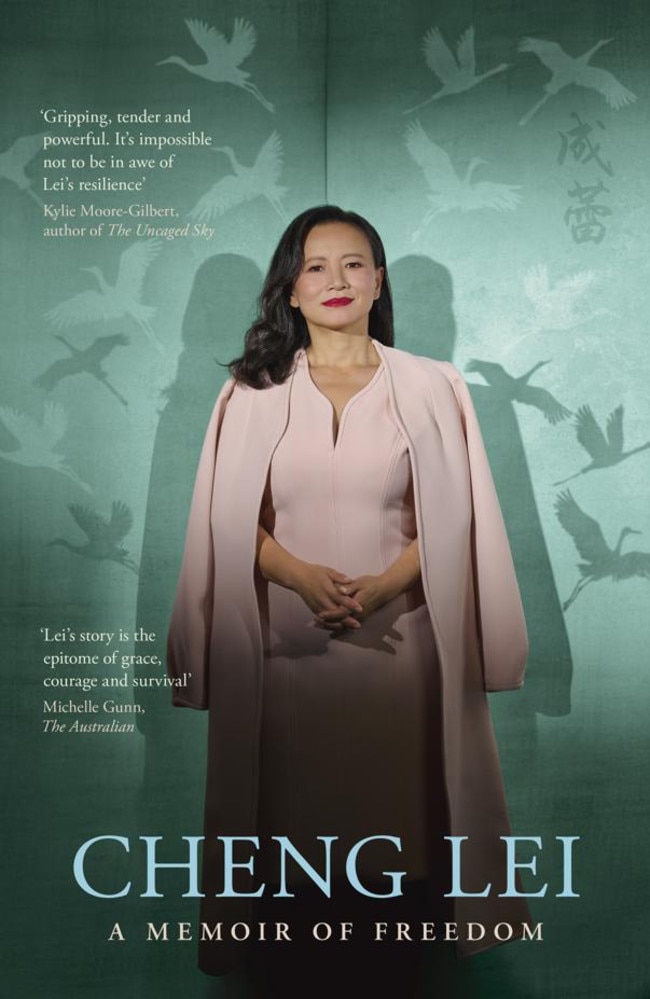

Cheng is now sharing her story via a Sky News documentary Cheng Lei: My Story and in a powerful new book Cheng Lei: A Memoir of Freedom.

Working on both has been a deeply cathartic experience, as has returning to screens as an anchor on Sky News.

“I’m trying to use the miserable time that I’ve had to endure to make something meaningful out of it, like writing this book, like being part of this documentary, so people know what China does behind closed doors.”

But returning to normal life is a long process and Cheng is still dealing with the trauma of her false imprisonment.

Some things will never be normal, though, like the high likelihood Chinese spies based here in Australia are monitoring her.

“I assume there is some monitoring, but I have a very fearless attitude. I was there, they could do [those things] to me, they can’t do that to me here.

“And I think if we live in fear and self-censor and always check ourselves, just in case China gets the s***s again, then what’s the point of freedom? We may as well be living in China.”

Cheng Lei: My Story is available to watch on Foxtel, Sky News Regional, Sky News Now or online at skynews.com.au from Tuesday June 3 at 7.30pm.

Cheng Lei: A Memoir of Freedom is on sale from June 4.

Originally published as ‘Torture’: Australian journalist Cheng Lei’s three years of hell in Chinese detention on bogus espionage charges