‘I’m going to die on the floor of a car park’

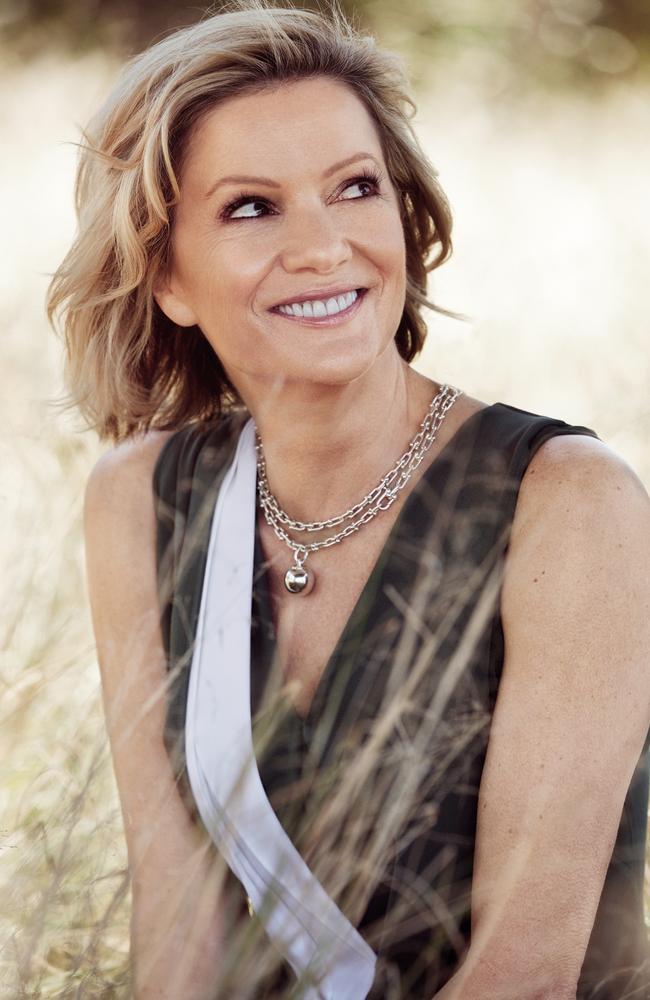

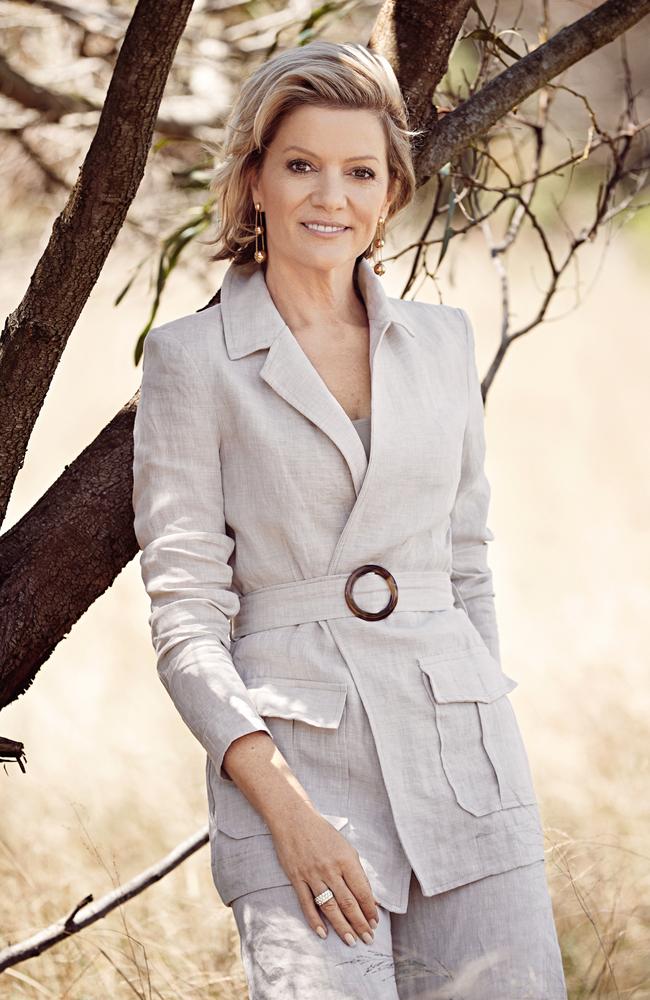

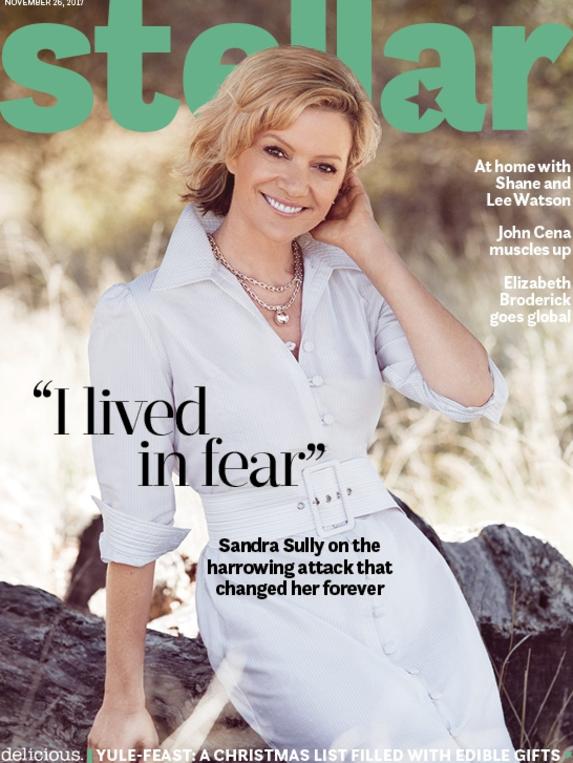

SHE is one of TV’s great survivors — but 20 years ago this month, Sandra Sully was attacked by a masked assailant who wrestled her to the floor of her car park, held a gun to her head and pulled the trigger. It changed her life forever.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT was something Sandra Sully wondered since she was a child. If she ever needed to scream for help, would the sound come? Or would terror paralyse her voice? She got her answer 20 years ago this month, when a masked assailant wrestled her to the floor of her car park, held a gun to her head and pulled the trigger. Sully believes her screaming saved her. “He was aware he couldn’t shut me up,” she tells Stellar. “I kept fighting and, at some point, he just decided he had to run.”

As he fled, he pulled off his balaclava and she caught the eye of the man beneath. Blond. Muscular. Menacing. He has not been caught, so Sully will probably never know why he attacked, why he chose her, or why the pistol didn’t fire. “For a long time, I looked for him,” she says. Occasionally she’ll still see a man in a crowd and wonder if it’s him.

The attack affected her deeply. “It was at least 10 years before I was ready to talk about it to anyone other than my family,” the Network Ten newsreader explains during a sit-down with Stellar. “And probably 15 years before I felt like I could put it behind me. I still don’t like to be surprised. If someone makes a loud noise, I jump. I am always aware in a car park. You realise life can be snuffed out in an instant.”

Perhaps it was the resilience she developed in the wake of the attack, or the way that brush with death forced her to re-order her priorities, that has helped Sully survive ratings wars, management coups and “bonings” to become one of the country’s longest-serving news presenters.

Her career began some 30 years ago, when the aerobics instructor and aspiring dental hygienist from Brisbane accidentally found herself in a newsroom. “I have worked with over a dozen female partners on Channel Ten and virtually all of them have fallen by the wayside,” says Ron Wilson, Sully’s long-time Eyewitness News co-host, who is now retired from television. “These were pretty tough women. But Sandra has survived all this time, and still has a smile on her face. If you can do that for this long, something is right.”

NOT long after midnight one November evening in 1997, Sully pulled into the car park of the apartment she shared with her then husband, Mark Ryan, in the inner-Sydney suburb of Surry Hills. As she opened the passenger door to get her bag, she became aware someone else was there. She looked up and saw a man in a balaclava walking towards her. Sully tried to get back into her car but he grabbed her by the shoulders, then her hair. “I started fighting,” she recalls. “He put a gun to my head.” She fought and screamed but he wrestled her to the ground. He held the weapon to her temple and pulled the trigger. “I thought, ‘Bloody hell, I am going to die. I am going to die on the floor of a car park. This is it.’” But the gun didn’t fire. He pulled the trigger again. Still nothing.

Sully was screaming. He tried to shut her up by slapping her around the head with the pistol, but it didn’t work. She just kept screaming. Suddenly he stopped. “He never said a word, he just ran,” she tells Stellar. “He ran through the car park and up the stairs.” Through a grill in the car park wall, she saw him again. “He ran by, and he looked at me.”

Sully thought he was coming back. Bleeding and terrified, she scrambled to the lift, praying he wouldn’t be inside it when the doors opened, or waiting outside her apartment. “When I got to my floor I was hysterical,” she says. “I remember screaming and belting the [apartment] door down, waiting for him to come upstairs, thinking he was coming to get me.” Ryan woke to her screams and let her inside. “I screamed, ‘He’s here! He’s here!’ I was completely hysterical.”

After the attack, a shell-shocked Sully went through the motions. She went to the hospital for X-rays, then to the police station to give a statement. The couple found a hotel room in the city; she couldn’t face their apartment again. “I went back for a week or so, I think, but I couldn’t function,” Sully says. “We had to move — we couldn’t afford to, but we had to go somewhere else and stop that getting in the press. I couldn’t bear anyone knowing where I lived.”

For a while she took refuge with her family in Queensland. “It was shocking,” her mother, Caroline Sully, remembers. “To think that can happen to your own daughter.”

Police treated the case as an attempted abduction — a set of handcuffs were later found at the scene. Yet they could find no motive. “I am not convinced he was a stalker,” Sully says now. “I think he had cased the joint and thought I was gettable.” She doesn’t know why the gun didn’t fire. “The cops at the time said it might have been a replica.”

Most of Sully’s questions are unlikely to ever be answered. The emotional recovery took years, made worse because her attacker was still at large. Perhaps he was watching her, waiting to try again. “You live in fear,” she says.

In 2000, her marriage to Ryan broke down — partly, Sully says, because of the stress the attack put on the relationship. Living alone was frightening. For 10 years she had a security detail. “I had ex-federal police officers spend time with me,” she says. “They would come running in Centennial Park with me because I couldn’t run on my own. Fitness has always been a big part of my sanity, but I couldn’t leave the house. My parents came to stay for a while. Then I worked out you have to cope.”

Through it all, work gave her comfort. “I love my job, and coming to work every day gave me purpose.”

Wilson credits Sully for putting on a brave face. “To the rest of us in the newsroom, you would hardly have known.” She didn’t publicly address the attack until six years ago — and has never spoken about the assault in detail until now.

“I am OK to talk about it now because it’s been 20 years,” she says. Sully doesn’t want the attack to define her, but it has left its mark. She is fearful, sometimes, but also resilient. And she is careful about protecting her privacy. “The assault helped me define where my barriers were,” Sully says. “I don’t chase publicity for publicity’s sake. Sometimes I think that’s probably hurt me, but it doesn’t fulfil me. I’ve seen the ugly side of that. No regrets. It’s made me a lot stronger.”

Tears fill Sully’s eyes only once during her long talk with Stellar. And it’s not when she talks about her attack. It is when she speaks about self-doubt. Sully says she never aspired to be on television. As the youngest of four growing up in a working-class family in the Brisbane suburb of Tarragindi — her twin sister beat her into the world by half an hour — she dreamed of becoming a dental hygienist.

Soon after leaving high school, she became an aerobics instructor — complete with 1980s leg warmers and leotards — and ran a gym chain while studying community fitness at night. Yet she was still restless. “I knew there was more to life, but I wasn’t sure what it was.”

A gym client told her about a job as a production assistant with the Seven Network’s State Affair, and soon she was typing scripts, applying the presenter’s make-up, booking travel and rolling the autocue. “I fell in love with television,” she says. A year later, the show was axed and she ended up managing the newsroom.

At first she was still typing scripts. But Sully was eager and curious, and was soon offered a cadetship. “I had all the self-doubt,” she says. “Was I worthy? Was I good enough?” Her eyes well as she recalls the moment. “I didn’t want to embarrass myself and my family. I was so self-conscious. I had never stepped outside my comfort zone.” She took the job, although she almost turned it down. “I think everyone lives with impostor syndrome. You really struggle. I just knew I had fallen in love with journalism.” The self-doubt has ebbed, but it is still there. “Always, to a degree.”

Naysayers warned she’d never make it. “I was always told my voice was crap,” she says. “The tone was wrong, the timbre was wrong, the inflection was wrong. [A voice coach] really forced me to confront those fears. Really, it was more about a sense of failure. But I dug deep, and thought, ‘Do I want to live a life of regret, or do I want to have a go?’”

Sully was a reporter in Sydney when she was called into the boss’s office one Friday and asked to co-host the re-launch of Good Morning Australia the following Monday. “I remember shaking so hard my foot came out of my shoe and I didn’t even know it,” she admits.

That was the start of her presenting career, but it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. At times she has been axed for other people; sometimes they have been axed for her. There have been corporate changes, cancelled shows, and failed experiments. “My whole experience has been upheaval after upheaval,” she says, “and navigating a way through the madness.”

Wilson credits Sully’s easygoing personality for her survival in the TV industry. “Every single person who works in television — it’s a bit like politics — they really want her job,” he tells Stellar. “It’s a fine line between defence and being professional. A lot of high-profile TV people can be a little precious, a little princess-y, but Sandra is not one of those.”

While she may be no princess, Sully has come to slyly embrace her unofficial title with younger viewers: “Queen Sandra”. When The Bachelor Australia premiered in 2013, she proved a good sport, playing along with a supposed feud with fellow night-time presenter, Bachelor host Osher Günsberg.

“Sandra is always up to play around with ‘newsreader gone rogue,’” Günsberg tells Stellar. “She has a brilliant sense of where the line is that would affect her ability to deliver the news — and often sails very close to that line.” And yet, he adds, “She is the most professional person you’ll meet. It would be hard to find anyone more respected around the halls of Ten.”

Even so, there is a sense that all of this is because Sully refuses to let herself care too much. She has other things in her life — charity work, a seat on the board of Hockey Australia, and there is also her role co-hosting the annual Australia Day Concert at the Sydney Opera House to look forward to in the new year.

Most important of all, however, is family. She married banker Symon Brewis-Weston in 2011, and is stepmother to his 12-year-old daughter, Mia. “She and Symon have both been gifts,” Sully says. “Work doesn’t define me. What is really important to me is family and friendships, and making sure my life is fulfilled in other ways.”

Originally published as ‘I’m going to die on the floor of a car park’