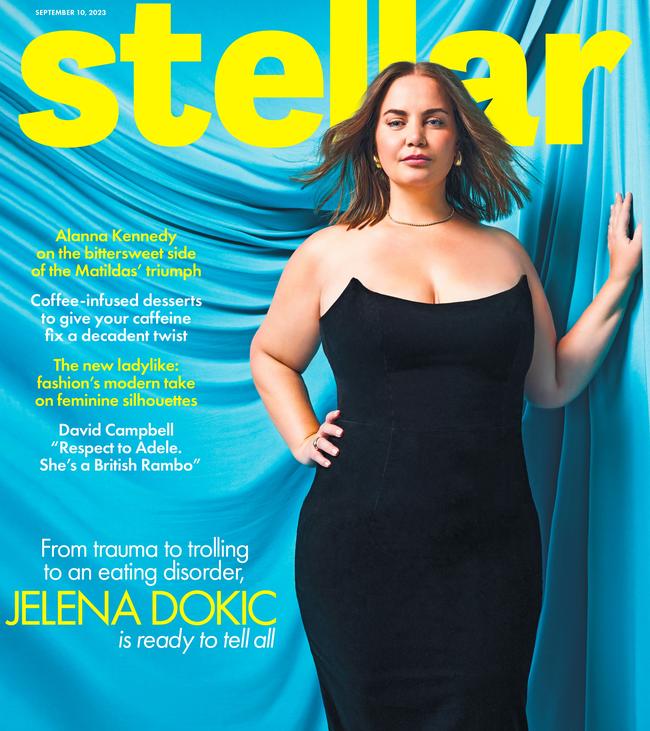

Exclusive: Tennis star Jelena Dokic reveals eating disorder

Months after she was mercilessly trolled by nasty body shaming critics while commentating the Australian Open, tennis champ Jelena Dokic has opened up for the first time about her struggles with disordered eating, brought on by years of trauma.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Four years after she retired from professional tennis, former World No.4 Jelena Dokic chronicled the years of physical and verbal abuse she had endured from her father in a best-selling memoir in 2017.

But her traumas weren’t over.

First came the split from her partner of 19 years, then came the torrent of online bullies who body shamed her relentlessly on social media.

Through it all, she reveals in a new book, she was also struggling with disordered eating, which only compounded her depression and shame.

But, she tells Stellar with adamant belief, these travails have only hardened her resolve to back herself: “I really believe I can find the way.”

Enjoying a holiday in Europe after finishing her broadcasting duties at Wimbledon for the Nine Network in July, Jelena Dokic did what most tourists do: she snapped a photo of herself looking cute in a green swimsuit and flowy white pants, and posted it to her social media.

But this simple act was one of defiance for the former tennis champion turned author and commentator.

While her television star has been rising steadily since becoming a key member of Nine’s coverage of the Australian Open and international tennis in 2019, Dokic has experienced a constant barrage of cruel online comments and cyber-bullying in parallel with her success.

Targeting her size-16 figure, trolls have called her a “whale” and a “pig”, and complained about how she looked on television.

Then, when she vented her frustrations about the taunts and provocations in subsequent posts, they flooded her direct messages with more invectives. Until this year.

After receiving a particularly nasty sequence of remarks in January, Dokic put her detractors on blast, revealing their hurtful words and responding to them on Instagram.

“THE ‘BODY SHAMING’ AND ‘FAT SHAMING’ OVER THE LAST 24 HOURS HAS BEEN INSANE,” she wrote, adding, “The most common comment being ‘what happened to her, she is so big’? I will tell you what happened, I am finding a way and surviving and fighting.”

Something changed with that post.

“I could feel something shift,” the 40-year-old tells Stellar.

“The media, people, everyone was like, ‘OK, enough is enough.’ People were stopping me at the Australian Open, journalists were writing articles, people on social media were supporting me – and men, as well, which I’m really grateful for.

“And to be honest, the comments have stopped. You have to remember anything that’s bad in the world, any abuse – that includes body shaming, bad comments and being unkind – they thrive in silence.”

Dokic has become all too familiar with that lesson. Her silence ended the moment she released her best-selling memoir Unbreakable in 2017.

In it, she recounted the shocking physical and mental abuse she suffered at the hands of her father, Damir Dokic, from the moment she picked up a tennis racket at the age of six.

At times, she wrote, she was beaten so badly that she lost consciousness, and if he wasn’t hurting her, she was trying to hurt herself because of the trauma.

The former World No.4, Wimbledon semi-finalist, and Australian Open and French Open quarter-finalist – whose family escaped war-torn Croatia (then Yugoslavia) in 1991 to become refugees in Serbia, before leaving for Australia in 1994 to become refugees a second time when she was just 11 years old – says telling the story of her harrowing ordeals was life-changing.

“I did not start living until Unbreakable came out. I was existing in silence, in shame and embarrassment,” Dokic explains.

“I kept thinking that something is wrong with me – there’s this stigma around abuse. But the day that Unbreakable came [out] just lifted a huge weight off my shoulders. And I unburdened all of this pain.”

One particular epiphany Dokic reached when working on the book with Walkley Award-winning co-writer Jessica Halloran was that abusers retained control when their victims were silent.

“Once you open that up, you get it out in the open, they lose their power,” she says.

“It’s like that with everything. Whether it’s about the abusive situation with my father, whether it’s mental health, whether it’s body shaming.”

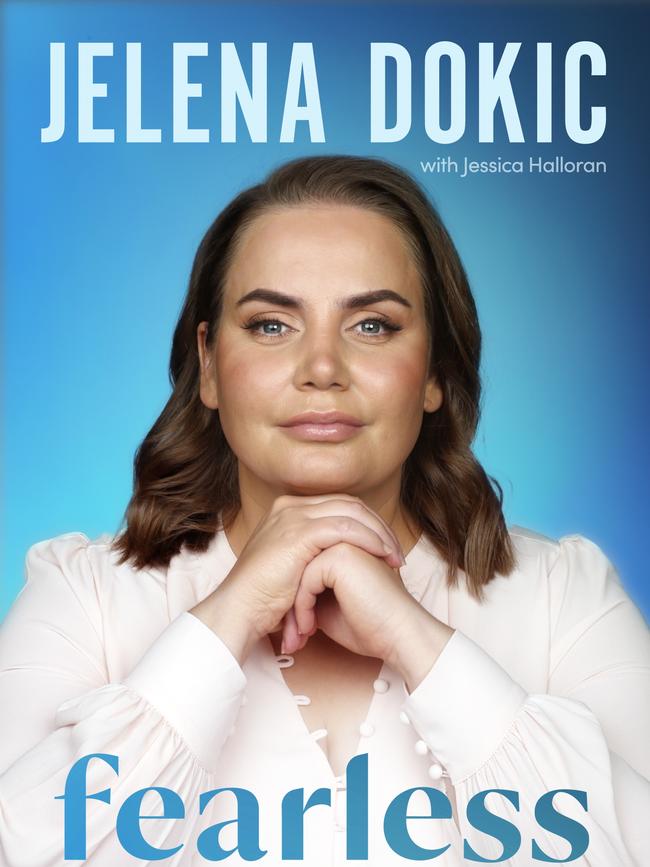

Motivated by how she reclaimed her own strength through finding her voice, Dokic worked with Halloran again to write her new book Fearless: Finding The Power To Thrive, an in-depth account of the severe depression, heartbreak, healing and hope she’s experienced since Unbreakable. With admirable candour, she reveals for the first time her struggles with disordered eating and how it manifested itself.

“I actually haven’t talked about my eating disorder [before] because, for so long, I didn’t understand it,” she explains.

“But now I know that more than 90 per cent of people that do have eating disorders, it comes from trauma.”

Her complex relationship with food, Dokic recounts, began when she was a refugee in Serbia. Those childhood years were gripped with hunger as her family had limited access to water and whatever staples they did have would be spoiled by rats or mice. Then, when her tennis career started, her father weaponised food, controlling what and when she ate, and denying her meals after practice.

After one successful tournament, her dad bought her three Oreo biscuits as a treat but told her she had to make them last for weeks.

![“I didn’t know how hard [the break-up] would hit me,” she tells Stellar of her split with her partner of 19 years. Picture: Sam Bisso for Stellar](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/358fafd9ce3eea1ac9764aed4a53d57f?width=650)

Fleeing her father’s grip in the middle of the night in October 2002, a then 19-year-old Dokic turned to food for comfort. Later, there were days she would eat two breakfasts, two lunches and two dinners.

Sugar became her salve, and it was not unusual for her to buy a whole cake and eat five slices at a time. The bingeing was followed by periods of starvation – the cycle ultimately wreaked havoc on her body and, along with injuries, forced her to retire in 2014.

“By early 2017,” she writes in Fearless, “I weighed 120 kilograms, almost twice the weight I’d been when I played. The shame returned, and I didn’t have the skills to cope with my emotions around it all.”

In 2021, Tin Bikic, Dokic’s partner of 19 years, ended their relationship during a FaceTime call two days before Christmas while he was in Croatia and she was alone in Melbourne.

Bikic and his family had become her safety net after she cut off contact with her father, so the emotional upheaval that came from the split left Dokic reeling.

Her cycle of bingeing intensified and in April 2022, she nearly took her own life.

“I didn’t know how hard [the break-up] would hit me,” she tells Stellar.

“I’m quite a sensitive person and when I love someone, I really do it, you know, a million miles an hour with my full heart. Ultimately it was very hurtful that it ended. I also almost felt like a bit of a failure, as well.”

The intensity of her downward spiral made Dokic realise something was wrong, so she sought help from a psychiatrist who reminded her that she was suffering from PTSD caused by childhood trauma.

“Getting professional help saved my life,” she says.

But she also admits, “I find the eating disorder quite complex. I’m working really hard on it. But the writing of the book has been a massive step for me because I’ve realised I’m not eating like that anymore. I’ve got more balance now.”

However, Dokic wants to make it clear that, whether or not people have an eating disorder, no-one should be commenting on people’s bodies.

“I’m not defined by, and I’m not, my measurements,” she states.

“I’m my work ethic. I’m my IQ. I’m my kindness. And you know how good I am at my job. To be honest, I’m proud of how I’ve been able to continue to reinvent myself.”

Not only has Dokic pivoted to becoming a respected sports analyst and public speaker, she’s also been able to forge ahead as a single woman. While Dokic says she’s not ready to date again, her separation hasn’t made her give up on romance.

“I absolutely believe in love and I’d love to go find it again one day,” she insists.

“I’m not there yet, but there will come a moment. We know by now that I believe there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. I believe in the best. And I believe in that happy ending. I think ultimately my story is that.”

While she’s proud of her record in tennis and the career she has built under extreme circumstances, Dokic says finding her voice is her finest accomplishment, and she refuses to be bitter about her father.

“When you’re not able to even say sorry or try to have a relationship with your daughter, I think that explains the person he is,” she says.

“I don’t hate him, but it doesn’t matter about him. This is about me reclaiming my power and my life and my voice.”

Dokic has found new purpose in becoming a beacon for others who may not have a platform.

“Some of the strongest people I know have gone through literally hell and back and dealt with depression or anxiety or eating disorders,” she notes.

“There is this kind of thinking that if you do have something like this, it makes you weaker. But that’s completely wrong.

“People ask me all the time, ‘Where do you find strength?’ For me, it’s believing and having confidence in yourself that you can get through. I really believe I can find the way. That’s what got me through abuse.

“That’s what got me through being a refugee twice [and] being bullied in school and in the tennis world, as well as getting through my mental health battles and almost taking my own life.

“Every single day that I went through that, I had belief that I can get through it and that it’s going to get better and that I will find a way.”

With that, she adds, “I can, with 100 per cent confidence, say that today, I am probably the happiest and the most healed I’ve ever been.”

The following is an extract from Fearless: Finding The Power To Thrive by Jelena Dokic with Jessica Halloran (Viking, $34.99), out on Tuesday.

As you can see, eating is something I have trouble controlling. It’s emotional eating.

I’m very aware of that now, but I haven’t been until recently. Now I am working hard to heal, and I hope not to ever bear so much shame around my weight again.

I’m at a place where I feel comfortable in my own body, no matter what size I am.

As I write this book, my body image is something that for the first time in my life I am working through from a psychological perspective.

I mean, there was a point where I knew, you know, there was something going on when it came to my eating and my emotions – that there were triggers and certain reasons for my spiralling at certain times, but I never properly understood it until recently.

All these episodes from my childhood and youth, I really hadn’t made the connection to my disordered eating until a session with a psychiatrist in March 2022.

It might seem crazy to you that it took me so long to make those links, but it is what living with trauma does to you. When you are in the thick of it, you lurch from one moment to the next, just reacting.

All that reaction means there’s little left in your brain to try to analyse how you’ve got to where you are.

It really didn’t occur to me that my cravings, my bingeing, were in part due to what had happened to me in my formative years until the psychiatrist pointed out a couple of fundamental truths.

One: I had grown up worrying where my next meal would be coming from and if I would be full enough after eating it.

Two: I am still suffering the trauma of having lived in a highly abusive family environment for more than two decades.

At a session in July 2022 the psychiatrist connected the dots for me. He explained that food makes me feel good, it lifts my mind out of the darkness. I use it to control my feelings in a short-term way: eating makes me feel better for a bit, until the shame and sadness of overeating kicks in.

Eating gives me comfort and doesn’t disappoint like so many other things in my life did. I found comfort and safety in food.

Since then I have read that 90 per cent of disordered eating happens because of traumatic events.

My weight is not only my own private issue, as I’ve found since establishing my TV and commentary career, and having a public profile.

life in the public eye

From a young age, I became accustomed to living a public life. Of course, being in the public eye was awful at times – when my father was losing his mind throughout my greatest tennis years and causing me all sorts of grief.

Years on from that, some of the scrutiny has focused instead on my weight.

I have seen people look at me differently as it has fluctuated. I have seen the look in their eyes when I’m a smaller size. I’ve felt people embrace me more when I’ve lost large amounts of weight.

At times I have been treated with respect and celebrated for it.

At one stage, a few years ago, I was able to lose quite a bit of weight.

It took an enormous amount of work: I intensely watched what I ate, I found a love for exercise again. The smaller I became, the more I saw that look on people’s faces of ‘your body – and therefore you – are more acceptable now’.

People admired my ability to transform myself physically. The platitudes came my way.

But in the end I put a lot of that weight back on because what I hadn’t yet dealt with were the psychological and emotional aspects of bingeing and starving cycles.

What do those cycles look like?

I would sometimes eat literally ten times a day. I would eat the amount of food and calories you would usually eat in four or five days. I would have two breakfasts, two lunches, two dinners, consisting of things like five slices of cake, three burgers, two servings of fries, bars of chocolate, sandwiches for snacks.

But then I had the ability to starve myself.

I could go for six days without food – that was my record, and I would be training as well. By training, I mean playing at least five hours of tennis a day. Outside my tennis career I would do the same but instead of on-court training, I’d be going to the gym and running a lot. I would feel sick from too much food, and then I would feel unwell and dizzy from not enough food. I never felt good.

a vicious cycle

Because at that point, I wasn’t dealing with the root causes of my disordered eating, the cycles would repeat again and again.

And with that came the ‘looks’ and nastiness. I have had direct messages on Instagram accusing me of being ‘too fat’, ‘unrecognisable’. People would call me names like ‘whale’ and ‘pig’ on social media, and I’d overhear horrible comments, stuff like ‘What happened to her?’ One person even said that no matter how good a commentator I was, he couldn’t listen to me knowing I was fat. Of course, these messages and remarks make me feel terrible.

And, as I touched on earlier, I am not alone. Despite great work being done in this area by brave and brilliant women like Taryn (Brumfitt), we live in a body-shaming culture.

What I have learnt from speaking about my weight is that many people go through what I have gone through.

So many people have told me that their weight gain, like mine, comes from a painful place. They have also struggled and tried relentlessly to reduce their weight.

It’s extremely hard. I know this so well. It’s a battle.

I consider it a privilege that people are willing to confide in me and it’s a lot because I see their suffering too.

Studies have shown an unmistakeable connection between eating disorders and childhood trauma, but of course plenty of people who have a difficult relationship with food, whose body shape is larger than others, haven’t necessarily been through trauma or used food as a coping mechanism in the way I did.

Either way, being body-shamed is a terrible experience and is never okay.

I won’t always let the hateful comments on social media slide. Early in both 2021 and 2022 were two occasions when I’d had enough and decided to respond to the latest slinging I was getting in my DMs and publicly. In February 2021 I wrote a post calling out these anonymous keyboard warriors. With this post I wanted to remind people that they never know which battle someone is fighting behind closed doors.

And so, for the first time I stood up to those who had negatively referred to my size.

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636. For domestic or family violence support, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732. For help with disordered eating, visit Butterfly at butterfly.org.au.

Originally published as Exclusive: Tennis star Jelena Dokic reveals eating disorder