Barry Gibb shares why he can’t watch parts of the new Bee Gees doco How Can You Mend A Broken Heart

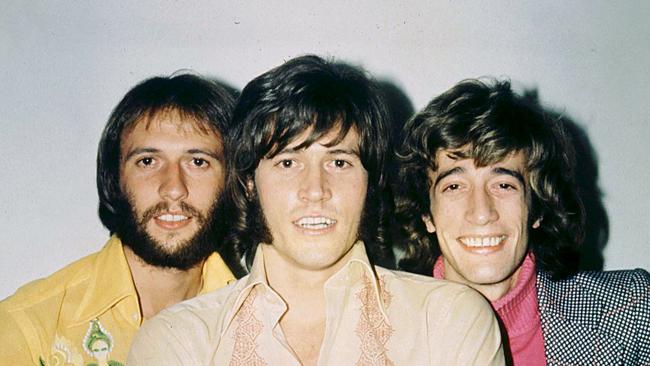

Barry Gibb shares the ups and downs of life as a Bee Gee and the “sibling rivalry” with his late brothers Robin and Maurice in a new music doco.

SmartDaily

Don't miss out on the headlines from SmartDaily. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There really is no mending Barry Gibb’s heart.

The sadness of the loss of his brothers – Andy, Maurice and Robin – weighs heavily in his voice, in his downcast eyes as he talks about the music documentary of the rise and fall and rise to legendary status of the Bee Gees.

Gibb starts out our conversation by declaring he hasn’t watched the How Can You Mend A Broken Heart film in its entirety. He can’t.

“I must confess I’ve only seen bits of it because I can’t watch the loss of all my brothers. I just can’t watch that,” says the 74-year-old singer, songwriter and hit maker.

Directed by Hollywood legend Frank Marshall, the doco deals matter-of-factly with the deaths of the Gibb brothers.

Just as he was attempting a career comeback, baby brother Andy died in 1988, aged 30, of myocarditis, caused by years of cocaine abuse.

Maurice also died suddenly, aged 53, suffering cardiac arrest due to complications from a twisted intestine in 2003. His twin Robin died in 2012 from cancer.

But How Can You Mend A Broken Heart is much more of an exploration of the sibling dynamic which made — and broke — the Bee Gees and their unprecedented success in reinventing themselves through the decades from ’60s balladeers to ’70s disco kings and ’80s pop stars.

The doco opens with the Bee Gees trio of Barry, Robin and Maurice as boys, living in Queensland, performing at clubs and hanging out on the Gold Coast and near their Redcliffe home. Gibb says the family made “plenty of home movies” during those formative years after migrating from the UK to Australia in 1958.

“Those films were from Surfers Paradise in 1961 and 1962, that’s when it was paradise. Dad bought the camera and then eventually Maurice ended up with it and that’s when we started filming silly movies,” Barry says.

“We would do shows on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, we didn’t go to school at that point, so we just had the time of our lives.”

Even as the trio gained popularity in Australia via the plethora of talent shows on television in the early ’60s and enjoyed a hit with Spicks and Specks, they were frustrated by their lack of chart success.

So with their father Hugh, they headed back to the UK in 1967 to launch an international career, inspired by the Beatles-led explosion of pop music.

They inked a management deal with NEMS, the company run by the “sixth Beatle” Brian Epstein, with flamboyant Australian impresario Robert Stigwood taking charge of the Bee Gees.

The three songwriters spent long hours writing in the studio, with New York Mining Disaster 1941 the first single Stigwood took to radio stations, with only its title stamped on the vinyl.

Many British and American radio DJs mistakenly believed it was a new Beatles single and instantly added it to their playlists.

The manager didn’t need to employ the same tactic for their second single To Love Somebody — a song originally penned for Otis Redding, who died in a plane crash before he recorded it.

By the time they released Massachusetts, the Bee Gees were inciting almost Beatlemania-sized fan riots in Britain and America.

“When the Beatles came to Australia, they had a million people in the streets of Melbourne; that never happened (to us),” Barry says.

“I always, always salute the people who changed the culture completely and that was them. Everybody wanted to be a Beatle.

“Paul (McCartney) came to our first real concert at the Saville Theatre in 1967 with Jane Asher and his words were ‘Just keeping going, lads’. I’ll never forget that. But a huge dream just came true and that was to have a sense of belonging in that environment, to be signed to the same company as the Beatles.”

After that heady period of early success, cracks began to appear in the Bee Gees brotherly bond as Barry and Robin began competing for lead singer status.

“Sibling rivalry. To tell you the real truth, we could not have been happier before we became famous,” Barry says. “Fame, yes, was the spur, but it’s also the cause of rivalry, that’s when the competition began. If a group becomes famous, then everybody wants to become the frontman and this was something we had to learn …. I don’t think we ever did.”

While fame did indeed create fractures in the sibling relationship, the Gibb brothers would reunite several times throughout their career and continue to create hits.

After the first dip in their fortunes, Eric Clapton — who was also managed by Stigwood — suggested the Bee Gees needed a change in scenery to get the creative juices flowing and recommended they go to Miami, where he had recorded his breakthrough solo album 461 Ocean Boulevard.

The Gibbs stayed in the same house and travelled each day to the nearby Criteria Records, where soul producer Arif Martin helped steer their next musical evolution through R & B to disco.

And discover the famous Barry Gibb falsetto which would make them one of the biggest pop artists in history through the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack and its hits including Stayin’ Alive, Night Fever and How Deep Is Your Love.

“In 1971, ’72 we couldn’t get arrested in London and by 1975, when we went to Miami, we had to change, we could become more adventurous with our harmonies and vocals,” Barry says.

“Jive Talkin’ was the turning point for us. But I think the one thing in our lives that was always true, was that we were always naive. We never knew what was going to happen next, what we were going to write next.

“And if your brothers, you continue on, whether you get on or not. Sometimes we didn’t get on but most of the time we did.”

The Bee Gees next evolution is one Barry has dreamt of for decades.

Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook Vol 1, will be released in January and features the elder Gibb reinventing their classics in the country and bluegrass vein, with collaborators including Jason Isbell, Keith Urban, Sheryl Crow, Alison Krauss and of course, his lifelong friends Dolly Parton and Olivia Newton-John.

Bluegrass hero Ricky Skaggs invited Gibbs into the Nashville country clique in 2012 when they paired on the track Soldier’s Son.

“I’ve always been a sort of hidden country artist, you know,” he says.

“I got to make a record with Ricky Skaggs and that was an inspiration (for Greenfields) because it was like somebody saying ‘Welcome, come in, it’s OK. Nashville is that kind of place.

“Having any kind of success with any artists from Nashville is the cherry on the cake for me. In Nashville, a great song is a great song.”

Bluegrass hero Ricky Skaggs invited Gibbs into the Nashville country clique in 2012 when they paired on the track Soldier’s Son.

“I’ve always been a sort of hidden country artist, you know,” he says.

“I got to make a record with Ricky Skaggs and that was an inspiration (for Greenfields) because it was like somebody saying ‘Welcome, come in, it’s OK. Nashville is that kind of place.

“Having any kind of success with any artists from Nashville is the cherry on the cake for me. In Nashville, a great song is a great song.”

The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart is in cinemas on Thursday.

More Coverage

Originally published as Barry Gibb shares why he can’t watch parts of the new Bee Gees doco How Can You Mend A Broken Heart