‘Significant red flag’: Horrifying text 1 in 3 Australians have received

A staggering 1 in 3 Australians have received a text considered “a significant red flag”, revealing an issue some experts say we don’t take seriously enough.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

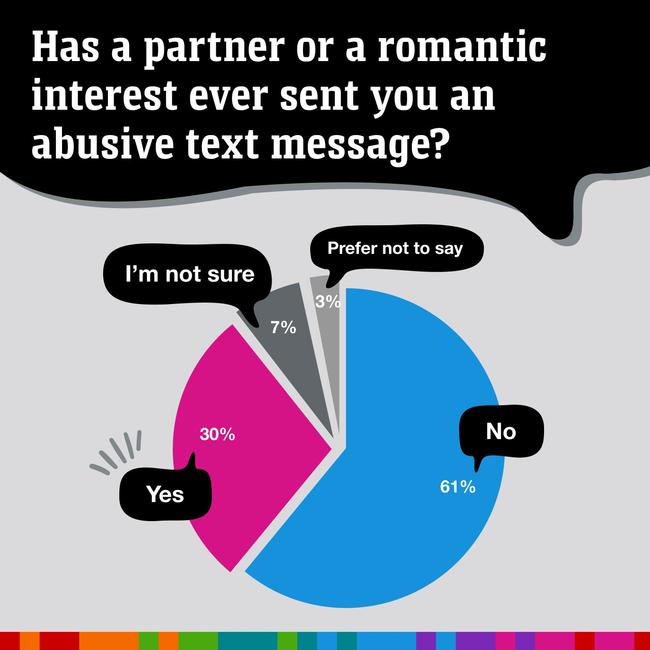

A staggering 1 in 3 Australians have received an abusive text from a partner or romantic interest, new research has found, “a significant red flag” that some experts say authorities do not take seriously enough.

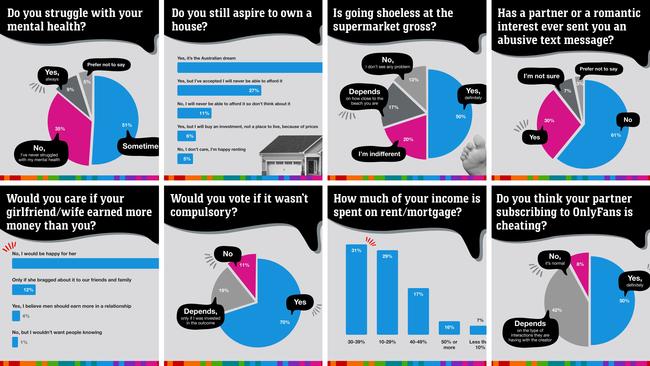

Of the more than 54,000 people who took part in The Great Aussie Debate — a wide-ranging, 50-question survey news.com.au launched earlier this year, uncovering what Australians really think about everything from the cost of living and homeownership to electric vehicles and going shoeless in supermarkets — 29.87 per cent (or 16,293) respondents reported experiencing some form of technology-facilitated abuse.

Defined in a piece for The Conversation by RMIT criminologist Anastasia Powell, this form of interpersonal violence involves the use of mobile phones or other digital technologies by perpetrators to harass, monitor, cause fear, or otherwise inflict harm, and extend the reach of their power and control over their victim.

Though such tactics overlap with those deployed by perpetrators of other forms of domestic and sexual violence, tech-facilitated abuse is particularly insidious because of the seemingly innocuous and commonplace ways it can manifest.

Its harms are also often downplayed due to the lack of physical scars it leaves.

Only 8.6 per cent of Australians over the age of 70 said they had received an abusive message — likely due to less reliance on mobile devices.

But among younger generations, for whom a smartphone is guaranteed in almost every pocket, the incidence rate was far higher.

Nearly 1 in 4 (23.57 per cent) of those aged 18 to 29 and 1 in 3 (34.83 per cent) of those aged 30 to 39 had gotten an abusive text from an intimate partner at least once.

These statistics hardly come as a shock. A landmark 2022 study by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) found half of all Australians had experienced tech-facilitated abuse at at least one point in their lifetime.

“Given the near-universal use of mobile phones, it is sadly not surprising that this form of abuse is so common,” a spokesperson for the federal government’s independent regulator for online safety, eSafety, told news.com.au, describing the receiving of abusive and threatening text messages as a “serious and widespread problem”.

Its frequency has increased in tandem with the migration of other facets of our lives — especially our relationships — to the digital realm, Professor Powell, who specialises in prevention, policy and practice reform addressing family and sexual violence, said.

“Widespread mobile ownership has naturally seen a shift where a lot of behaviours that occur face-to-face now also take place online or via digital communications,” Professor Powell told news.com.au.

“It is true of friendships and flirting and arguments. And it is also the case that mobile and other tech is commonly being used in violence and abuse.”

Similar to all forms of domestic and sexual violence, female and non-binary Great Aussie Debate respondents were more likely than their male counterparts to fall victim to tech-facilitated abuse.

Approximately 1 in 3 (30.25 per cent) of women said they had, compared to 29.38 per cent of men. Non-binary Australians overwhelmed both demographics, with 36.21 per cent reporting they’d received an abusive text from an intimate partner.

Research published in 2023 by Professor Powell and Monash University Associate Professor of Criminology, Asher Flynn, also found that experiences of it differed depending on gender.

“Women are more likely to receive abusive communications of a sexual nature, or that threaten harm towards them,” Prof Powell explained.

It also, she said, rarely exists in a vacuum — often taking place within the context of other controlling behaviours or physical violence, “especially where that tech-abuse is ongoing, or has been increasing”.

“While not every text message that name-calls or directs an expletive towards a partner is necessarily a sign that there is abuse in the relationship, a pattern of tech-based abuse is very common in domestic and family violence,” Prof Powell said, or can be a “warning … that there is a risk of physical violence” on the horizon.

The eSafety spokesperson echoed Prof Powell’s sentiment, noting that “while a single message might seem minor, repeated abuse can cause deep psychological and emotional harm, especially when part of a broader pattern of controlling or violent behaviour”.

Though Prof Powell acknowledged police and justice responses to abuse have greatly improved in recent years, there are still victim-survivors “falling through the gaps in the system”.

“Even women who have a protection order in place say police are often reluctant to charge a perpetrator for breaching the order,” Prof Powell wrote in The Conversation.

“That is, unless the breach is a physical assault or a physical trespass on her property.”

Similarly, in instances where there has clearly been image-based abuse, threats of harm, or stalking, “some victims are still being told by police that there’s no crime or nothing that can be done”, Prof Powell said.

“So, police do need training to recognise the seriousness of tech-based abuse, and its role in domestic and family violence,” she said.

“And I think the community generally needs to be more aware that a pattern of insulting, threatening, controlling or stalking messages from a partner, ex-partner or family member, is a significant red flag for family violence risk.”

In November, the federal government announced it would invest $3.5 million toward round-two grants to protect women from tech-facilitated abuse. eSafety has also launched the Technology-Facilitated Abuse (TFA) Support Service, which provides targeted advice to frontline workers and organisations, like 1800RESPECT, that support Australians affected by tech-facilitated abuse.

“These frontline workers can contact eSafety for practical support and advice when supporting clients experiencing technology-facilitated abuse, and can also submit reporters on behalf of their clients through eSafety’s complaints schemes,” their spokesperson said.

“Where additional help is needed to assess whether reported behaviour meets the high legal threshold for adult cyber abuse, including cyberstalking, doxxing or tech-based coercive control, reports can be made to eSafety’s Adult Cyber Abuse scheme.”

If you’re experiencing this kind of abuse, support is available. Visit esafety.gov.au to report serious online abuse or find advice about staying safe online.

Originally published as ‘Significant red flag’: Horrifying text 1 in 3 Australians have received