‘Uncomfortable, polarising’: Michael Zavros’ provocative new exhibition opening at QAGOMA

As a young boy Michael Zavros would visit the Queensland Art Gallery, now his exhibition will open there in the culmination of a lifelong dream.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Michael Zavros paints beautiful objects beautifully.

Aspirational objects – fashion, luxury cars, swimming pools, floral arrangements, horses and purebred chickens – are painted in detail and immaculately finished.

Then there are the fictions that unite these subjects, like centaur-style hybrids – horses that segue into men in high-end evening dress and, in 2021, his son Leo (then aged 10), as a centaur staring audiences down, armed with Cupid’s bow.

Zavros' realist method sees his work compared to photographs, yet its subject matter and its contradictions expose them as imaginative confections.

Born in 1974, Zavros is a Brisbane identity often featured, immaculately dressed, in the social pages with wife (curator, writer and editor) Alison Kubler.

However, mostly he can be found in shorts, T-shirt and crocs at home in the studio.

He lives down a quiet dead-end street on acreage on the edge of Brisbane.

Here he works among a collection of books, taxidermied animals and other curiosities – including a life-size mannequin known as “Dad” who features in a series of photographs, standing in for Zavros himself.

Outside are grazing horses, one of whom occasionally wanders through the studio, and exotic chickens. The paintings made here might look seamless, like a connection between Zavros’ life and art.

Within this artistic bubble he constructs visions that have baffled and entranced observers for 25 years. His Greek heritage, myths, art and its histories are central, as is the depiction of a perfect family. Yet his work suggests that aspiration is empty, mortal, but also compelling, an endless cycle.

Zavros graduated from the Queensland College of Art in 1996 and has experienced success as an artist since early in his career. His collectors and representative galleries are among the most influential in Australia and New Zealand.

Yet in the past 15 years his work has become uncomfortable for some, even polarising, as his own life and the images of his children have infiltrated his art as both subject and muse.

This month, Zavros' career is the subject of a survey at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) on Stanley Place in South Brisbane. While he has had many solo exhibitions, including interstate and overseas, this one is special for him.

Titled The Favourite, it brings his practice home to show in the place to which he aspired as a young boy, when he was growing up on the Gold Coast.

“I remember coming to the gallery on a school excursion and seeing the haystacks by William Delafield Cook and being so excited by what I was seeing, but really challenged, just thinking, ‘I couldn’t paint like that, I really want to paint like that’,” Zavros says.

“I wanted my work to be on the walls there. It was a pivotal moment.”

The Favourite was Zavros' chosen title for the exhibition.

“It’s a layered, loaded title that can go in lots of different directions. Whether it relates to horses – the favourite for a race – or a room full of favourite artworks, or the chocolate box reference to Cadbury’s Favourites and that certain kind of realist painting … (even) favourites in families – why would one child be favoured over another? I quite like those ambiguities.”

The exhibition includes paintings, sculpture and photographs, with two new installations that mark a change from the craft of painting individual works on canvas.

“That has been the biggest shift in my practice in recent years,” he says.

“I first put down the brushes to start making bronze sculptures and that worked … you have these successes, and demonstrate that you’re not just a painter.

“It’s a growing, incremental confidence about working in a very different way.”

The first of these is The Acropolis, a mural that signifies the heights of Greek civilisation and refers to Zavros' Greek-Cypriot heritage.

This painting, completed with assistants, spans the entry wall of QAGOMA’s Turbine Hall and is designed to provide an Instagram moment for viewers – which acknowledges Zavros' love of social media.

The second is Drowned Mercedes (2023), a luxury car filled with water, fabricated by others to his specifications.

“It exists as this incredibly beautiful folly – like so much of what I paint and what will be in the show. It is a folly, a ruin and, I would say, made so much more beautiful in this ruined state,” Zavros says.

“I really love being more of an art director sometimes … it meant that I could segue into realising projects like Drowned Mercedes which is very hands off. In my early career I didn’t assume I could be that kind of artist, but I admire so many artists who are, such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, who are often more like directors of their studio.”

The exhibition also includes paintings that have brought significant attention and disquiet. The first of these to come to national attention is Phoebe is Dead/McQueen (2010), which won the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize ($150,000).

It explored then five-year-old Phoebe’s childhood game of playing dead, covered in an Alexander McQueen designer scarf, and explores every parent’s greatest vulnerability.

Zavros recalls: “People were confronted that I would paint my daughter as if dead. It was confronting for me too. I didn’t see that as a criticism. Some people thought it was good, interesting, provocative. Others found it inappropriate.”

For Zavros, exploring images of his children (Phoebe, now 17, Olympia, 15, and Leo, 12) in his work is something that he is compelled to do as an artist, albeit being at times “confronted as a parent”. “I niggle at my own anxieties and everyone else’s,” he says.

It is a brave move, particularly during a period in which images of children have become so contentious. In Australia, photographs of teenage bodies by Bill Henson were censored in 2008, and this has paralleled growing public discomfort about imagery of children.

Zavros involves his three children in his work according to their own interests.

Phoebe acknowledges that this role is a natural outlet for her. It has been “one of our bonding things, that we would talk to each other about”.

As a young girl, she was intrigued by make-up, and “liked being older than I was”.

Paintings that dally with the disquiet include Amore (2018), which portrays Phoebe’s young face fully made up, full lips painted in red, with large gold hoop earrings older than her years. Zeus/Zavros (2018) depicts Phoebe and Leo in the swimming pool, Leo bare-bottomed and floating on a large white swan.

Zavros and Kubler were early adopters of social media, and Zavros' Instagram has more than 86,000 followers. He acknowledges this public gaze comes with some risk.

“There are definitely times where we feel exposed as a family. And the kids are good at it – except when they’re not,” he says.

“They’re young people, dealing with other young people in their lives. And that’s where we get protective or uncomfortable with the way we’ve been on display at times. But we’re all good at this thing that’s not quite a true account of our lives, it’s role-play. We smile for the camera. The kids know that I’m projecting an idea of something in my work. And that idea of art collapsing into life and back again – I think they have absorbed that.”

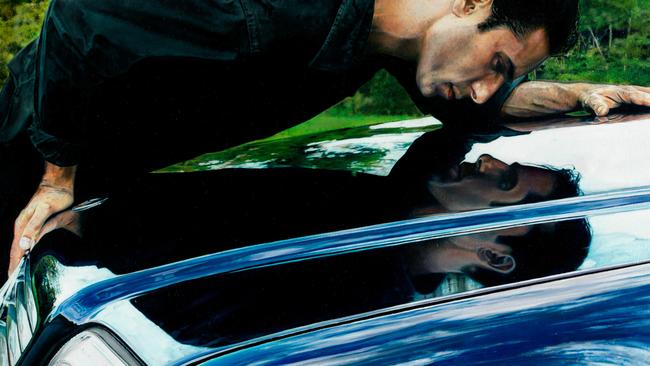

Paintings that riff on Zavros' appearance and status have also attracted attention, notably V12/Narcissus (2009).

In this painting, he stares into the bonnet of his midnight blue Mercedes, unable to tear his gaze from the reflection (like Narcissus from the Greek myth, who fell in love with his own reflection, with fatal consequences). While his work speaks to beauty, luxury and aspiration, this is not without critique or awareness of his own privilege.

However, for Zavros, art is not the place to argue for social change.

“A lot of artists today have a strong moral or an ethical bent in their practice. There’s this assumption that what flows from that is good art – because it comes from a good place. That is often not the case. The generation that came after me often has ideas about what they should be making work about. I do reject that. I worry that we’re losing some creative freedoms.”

This exhibition profiles a homegrown Queensland talent and the depth that has taken Zavros' work all over the world.

More exhibitions will follow in two of New Zealand’s major state institutions, but amid the attention, the artist continues to make and to dream, to realise objects that become something that they’re not.

Such as his floral arrangement still life painting The Phoenix (2015), constructed from a skeleton and an elaborately arranged bouquet, that transforms into a bird. Like so much of his work, he suggests it is “a kind of fake news, asking what you can believe – what is real? – to mock the very act of realist painting”.

Zavros' art is alluring, current in its concerns, with an enduring legacy.

He has earnt his place within the hallowed walls of the gallery he aspired to as a boy.