Trashed villas, shattered glass, piles of debris: Inside Qld’s run-down tropical islands

Feral goats roam freely inside trashed hotel rooms, pools are filled with putrid green water breeding mosquitoes and piles of debris litter the grounds of Queensland’s island resorts left to rot. SEE THE PICTURES.

It’s been 15 years. Fifteen years since a once-popular island resort just off Queensland’s coast was shut down in a flash.

Fifteen years of buildings left to decay and sprout weeds in the subtropical sun, of swimming pools collecting rainwater for mosquitoes to flourish, of feral goats clippity-clopping through smashed up bedrooms and using them as toilets, of backpacker beer nights amid the ruins.

Fifteen years of fairytales and nightmares, brewing enmities, of pig-headedness, of talk and little action by business and bureaucracy, of monumental disservice to a place that deserves much better.

Great Keppel Island, off Yeppoon in central Queensland, is a jewel, an island of 17 sandy beaches, inviting clear water, valleys of butterflies – and an unsightly scab festering in a corner.

They paved paradise then left it to rot.

Head up the coast, and the story is repeated. Brampton Island resort, closed and in disrepair for 12 years; Lindeman Island for 11 years; Long Island at Happy Bay for eight; South Molle for six; Hook Island for 10; Dunk Island for 12 and Double Island off Cairns for 11 years.

Some closed with grand plans that never eventuated.

Others were beaten about by cyclones.

Some are Chinese-owned, the deep-freeze of China/Australia relations during the Morrison government years turning abandoned resorts into a hot mess.

All but Dunk, a freehold property bought last year for about $23m by Annie Cannon-Brookes, wife of billionaire tech entrepreneur, Mike Cannon-Brookes, are leased from the Queensland government. That makes it the landlord.

So why, ponders Alice Robinson Lake, 23, from Perth, doesn’t it make the leaseholders, at the very least, clean up the site?

She’s strolling down the unkempt boardwalk on the edge of the sparkling sea towards the decomposing resort with her Sardinian friend, Maria Steri, 25.

The backpackers work at one of the two smaller resorts still operating on this section of the island.

But Steri has only been here a week and hasn’t wandered down this far before.

The smashed-up resort looms into view.

Her eyes widen. “This is terrible,” says Steri. “Horrible. Why is it like this?”

Good question.

TROUBLE IN PARADISE

Running an island resort is tough.

Building or refurbishing one is even tougher.

It has always been the case.

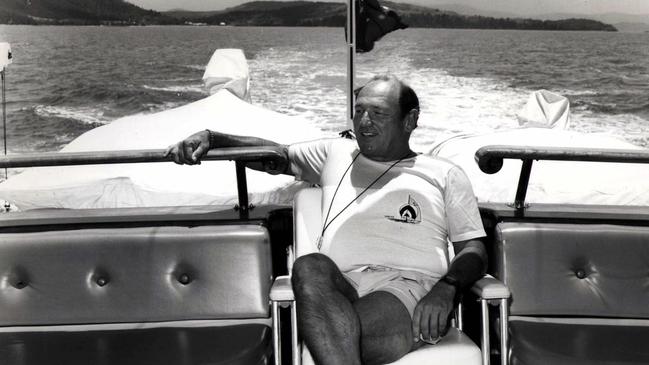

The flamboyant Vaughan Bullivant, who made his millions in vitamins then poured them into reimagining the Whitsunday’s Daydream Island in the 2000s, famously told how he would dry retch most mornings from the gut-churning knowledge he was losing $500,000 a month on his grand vision.

Bullivant spent about $75m on the resort, then offloaded it for $30m in 2015 to China Capital Investment Group.

CCIG also bought South Molle Island resort in 2016 – then Cyclone Debbie ripped through it in 2017.

It’s been gathering weeds ever since.

The age-old and increasing threat of cyclones, the global financial crisis and the loss of international visitors through Covid have battered island resorts in recent years.

But in the 1980s, it was the stock market crash and pilots’ strike.

In the 1990s, the Asian financial crisis thumped Australia’s tourism industry.

Expecting the unexpected is part of running an island resort.

Still, a wave of Australian investors has decided to take on the gamble recently, while, in the ever-shifting sands of island guardianship, Chinese groups bow out.

In the Whitsundays, the long-closed Long Island resort off Happy Bay is now in the hands of Melbourne-based Oscars Hotel Group, which is also buying the island’s Palm Bay Resort. Sunshine Coast developer, Shaun Juniper, and wife Samantha, are taking over the rundown Lindeman from Chinese interests, with plans for a health retreat.

Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest and wife Nicola, bought one of the dwindling number of operating island resorts, acquiring the lease of the exclusive Lizard Island in Far North Queensland.

Wayne Bunz, the national director of CBRE Hotels Capital Markets investment and brokerage, says the regeneration of Queensland’s islands is possible but owners need to choose plans wisely.

“Big master grand plans, they’re just too costly,” he says.

“Whereas an upmarket Lizard Island, or Qualia (on Hamilton Island, now owned by the Oatley family) or a 150-room family resort is more the type of thing that works.”

Regardless of the plan, the fact is operating a resort on an island is exponentially more expensive than on the mainland.

For a start, Bunz says, insurance policies are “beyond belief”.

“Then getting all the produce on, getting all the rubbish off, all the building materials on, all the old building materials off has a substantial cost,” Bunz says.

Now add the cost of power, water and sewage, which most island resorts provide themselves.

Then wages, far higher here than at the five-star Balinese and Thai resorts that continue to seduce Australians with their cheaper rates and exotic locales.

Plus, a range of rules and requirements apply when operating in Great Barrier Reef waters or national parks.

And if the plan is to rebuild because the existing resort is tired (a not uncommon scenario, Bunz says), good luck finding a bank that will loan big dollars for an island resort.

But don’t buyers know all that before they sign on the dotted line? Bunz laughs wryly. “People get ability and ambition mixed up,” he says. “There’s a lot of romance in buying an island resort.”

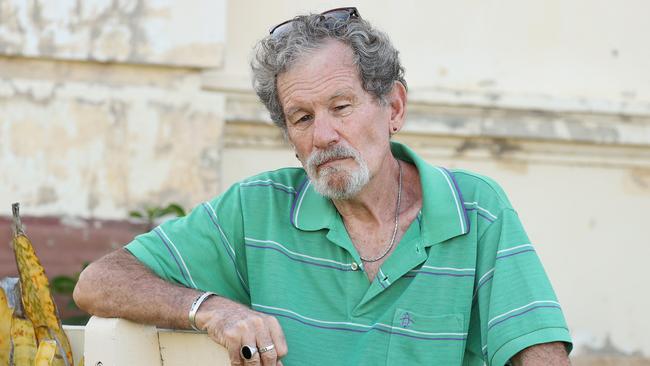

It’s true, says Richard Vanhoff, who has been marketing islands for close to 20 years, “every island owner I know has got to be half a nutcase”.

But he says, “they’re very strong business people and they have a vision. If they can’t go ahead with their vision, they get frustrated, they get cranky and angry.”

He says Terry Agnew, the owner of Tower Holdings which bought the Great Keppel Island (GKI) leases in 2006 for $16.5m, was a man with such a vision.

He wanted to build the next Hamilton Island on Great Keppel.

Vanhoff, who engineered the sale to Tower, argues much of the fault for the lack of action on GKI and other islands lies with the Queensland government.

Too bureaucratic, he says, too regimented, too slow.

Too beige when big vision entrepreneurs come knocking.

“Terry is an entrepreneur, he’s a very keen developer of a new generation,” Vanhoff says. “But ever since we lost (the developer of Hamilton Island) Keith Williams, the Queensland government has maintained a beat that says entrepreneurs will not be acknowledged. Keith was a visionary, he was smart.”

Sure, but Williams was the sort of bloke who would knock the top off a mountain to extend an airport, then ask for permission. Vanhoff hoots with laughter.

“That’s what he did,” he says, “I was there the day he did it.” Vanhoff recalls how, without telling authorities, Williams assembled a demolition and explosives team, then took off in his yacht, Achilles, to nearby Hayman Island.

“At midnight, boom. They blew up that whole section of the mountain and Keith was doing a, ‘What are you blaming me for? I wasn’t even on the island’.”

Vanhoff admits those days are gone but urges people to consider the legacy of entrepreneurs Christopher Skase, Alan Bond and Williams.

“Bondy was a scoundrel, he owed me a lot of money, I hated him, but look at the legacy he left with Bond University. Look at Mirage at Port Douglas; Port Douglas wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for Skase, even though people hated him. People bagged Keith but Hamilton Island is thriving and it’s giving the state and federal government plenty of tax money back.”

Today, he says, the government is beholden to “the minority position that strangulates” development. Does he mean environmental and Indigenous issues?

“Yes, also the narrow-mindedness of some people within government. We don’t want to see anything other than green, we don’t want motor vehicles, we don’t want this, we don’t want that.”

Tower’s initial vision for GKI was big. Huge.

A $2.6bn development spreading across the island, boasting three hotels, 1000 house and land packages, a similar number of apartments and townhouses, a 500-berth marina and retail village, two golf courses and an airport big enough to take jets full of tourists.

It was rejected by the Queensland government in 2008 on environmental grounds. The next slightly scaled down plan was canned by the federal government for the same reason.

But in 2013, after spending millions of dollars on the process, Tower got approval – with conditions – for a $600m resort including a 250-room hotel, 250-berth marina, 150 apartments, 750 villas and a golf course.

Once the approvals were gained, through the then state LNP and federal Labor governments, Tower announced it wanted a casino licence to attract international financing.

The LNP Newman government said no to a licence in 2014; Labor’s Palaszczuk government later rejected calls to create boutique casino licences for islands. Despite saying the project could go ahead without a casino licence, Tower put the development on ice.

It has since been trying to sell its leases and development approvals to someone who could realise the vision.

And the eyesore of the old resort remains.

‘IT’S JUST OUTRAGEOUS’

Just 22km off the coast of Mackay, the swimming pool that once jutted proudly into the clear water of the Great Barrier Reef is now crumbling into it.

Wind, rain and sun beat away at the concrete and bricks, no longer the hangout of holiday-makers relaxing poolside at Brampton Island resort. The last guests left in January 2011. Only a caretaker lives there now.

“It’s been sitting idle and deteriorating ever since and it’s just outrageous,” says Mackay mayor Greg Williamson. “It’s nothing more than land-banking.”

The owner, Brampton Enterprises, the directors of which are Melbourne businessmen, Avi Silver and Eddie Hirsch, the co-founders of United Petroleum, paid $5.9m for the lease in 2010, got council approval for an exclusive seven-star resort, had that extended … and have not proceeded.

Just why Brampton Enterprises has not started development is unclear because they’re not talking. Requests for interviews were not answered.

The same with Tower Holdings.

Five other current owners of island leases where resorts have closed – including those who have only recently purchased the property – also denied requests for interviews, with only Sydney property businessman, Glenn Piper, the new lessee of the cleared site at Hook Island resort, responding with written comments made previously.

Indeed, none of the leaseholders has made any submissions or given evidence at a 12-month-long, joint parliamentary inquiry into the problem of stalled island resort development, a fact the chairman, the ALP’s Shane King, calls disappointing.

The report is due on March 6 and King says while he offers no personal opinion, “the evidence seems that the big resorts of the past don’t work anymore. People would rather go to Bali. Eco-resorts or glamping may work better today”.

Other submissions, however, suggest the government should make developments more attractive to financiers by allowing strata-titling, and offer more infrastructure funding to assist developers.

Some argue leaseholders should pay bonds that are held until sites are cleaned up. King admits the need to streamline the three tiers of government bureaucracy involved in resort approvals “is something we kept hearing come up”.

Not only has Brampton Enterprises been silent with the media and the inquiry, it won’t reply to the Mackay council.

“They’ve been totally silent” for at least three years, Williamson says, but rates are being paid.

Vanhoff, who knows Silver, claims the development came up against state government bureaucracy and his interest cooled.

“Avi can be pretty hot-headed. Like Terry, he wouldn’t be the best candidate to sit in front of a bunch of bureaucrats. Because [bureaucrats] have no foresight whatsoever; they wouldn’t know what makes a business happen, yet they’ve got the right to make decisions. That frustrates guys like Terry Agnew and Avi Silver.”

Williamson is frustrated, too. He notes that the DA on Brampton is due for renewal in July this year.

“I would certainly be recommending to council that we don’t extend this DA,” he reveals. “Because obviously, they don’t have any intention of doing anything. And that just beggars belief.”

Lindeman Island is also on Mackay’s doorstep, and has not operated since 2012 when it was sold to China-based White Horse Australia Holdings, chaired by William Han.

A $600m master plan failed to materialise under its ownership.

The Junipers are now developing fresh plans.

“We’ve had owners, particularly of Brampton and Lindeman, who have supplied no interest at all in doing what they can for the Queensland and Australian tourism industry,” Williamson says.

“Why the heck did they get ownership of tourism leases on those islands? And why isn’t there, within the government lease system, a caveat about doing what you’re supposed to do in a tourism lease?”

There is, says Dan Collins, head of property law for top tier legal firm, Talbot Sayer. “It’s just not being enforced.”

Collins acted for Sunshine Coast-based Altum Property Group, which had its bid to buy GKI rejected by the state government two years ago after a Deloitte report found it did not have the financial capability to deliver the project.

So why doesn’t the government strip the leases from those who don’t comply?

“There’s a hesitation to take back that land because all of a sudden the liability, the repair and maintenance obligation, any council fees that need to be paid, that all falls to the state.

And the state doesn’t want that.”

Plus, Collins admits, any move to revoke leases could lead to lengthy legal battles.

Qweekend sought to interview Resources Minister, Scott Stewart, to ask why he won’t strip leases from any leaseholders in breach.

The request was denied.

Written questions were largely ignored in the statement that was received.

“These resorts are operated by private investors not the Queensland Government,” Stewart wrote. “The priority is to work with lessees and key stakeholders to facilitate redevelopment and rejuvenate island resorts in the Great Barrier Reef so the burden is not left with the taxpayer.”

In other words, it would cost too much. And so, a stalemate.

Stewart also confirmed industry chatter that in the past 18 months, audits have been, or are being, conducted on leases at Double, Hook, South Molle, Long (Happy Bay), Lindeman, Brampton and Great Keppel, as well as Stone, Keswick and Curtis islands, to gauge compliance with lease conditions.

He said his department “has a compliance framework to investigate, manage and enforce lease conditions”. How many leaseholders have received an enforcement notice is not revealed. Only one is publicly known.

Last year, leaseholder of Double Island in Far North Queensland, Benny Wu’s Fortune Island Holding Company, was instructed to have the island open to day-trippers by the end of March. The former hangout of Hollywood stars such as Keanu Reeves and Brad Pitt has been closed and out-of-bounds since Fortune Island took it over in 2012.

This year, workers have been seen travelling to the island, about 1.5km off Palm Cove, but local businessman, Tony Richards, who has long lobbied for the lease to be enforced or revoked, believes there’s “a snowball’s chance in hell” of having the rubbish removed, a jetty rebuilt, sewage and electrical issues resolved in time.

What will happen if the deadline is missed? The minister did not address the question.

FUTURE FOCUS

It popped up just before Christmas: a beach bar pumping out music and mojitos on the edge of the dunes of Great Keppel Island’s Fisherman’s Beach.

Then, in late January, the chairs were stacked, the music gone and it was closed.

Yet again, residents and surviving businesses on Great Keppel were left guessing about what was happening on their island home.

The bar drama was just the latest skirmish in the ongoing saga of Great Keppel, where rumours swirl in an information vortex.

Potential buyers have come and gone: an ultra-rich Singaporean couple, Altum, and the most recent suitor, mining magnate Gina Rinehart, who backed out in the days after last year’s May federal election.

Every time, hopes rise, objections rage, and unease reigns.

“There’s been that much conflict,” says Shane Bonney, the owner of island store, Tropical Vibes.

“You’ve got to watch what you say because you can stir people up.”

He’s not keen to talk about what he’d like to see happen, just that he wants something to happen.

And that, according to island buzz, is why the Keppel Beach Bar opened, using Tower’s mothballed liquor licence from the resort.

Because action was required.

Minister Stewart would not confirm this but Geoff Mercer, long-term owner of low-key GKI Holiday Village, says he did not have the impression that Tower was doing it because they cared; “I think [Tower] is doing something because they have to care.”

That’s also the view of Michael Powell, a member of an alliance against Tower’s plans, and moderator of the Facebook site, Don’t Destroy Great Keppel Island.

He claims Tower was told late last year to meet its lease requirement to operate a tourism facility. So, it erected the bar.

“Their attitude is, ‘You want a tourism facility, you’ve got one’,” Powell says.

But not anymore.

A series of problems sounded the bar’s demise, at least for now.

The only nearby toilets – operated by the Livingstone Shire Council – were inadequate for demand.

Patrons were seen urinating in the bushes.

Loud music upset residents.

A diesel generator was filmed gushing black smoke.

Then the bar’s food van blew up, igniting nearby bush.

Andy Ireland, Livingstone’s mayor, says the structure complied with Tower Holdings’ approvals but the shire has issues with the smoke pollution, food licence and toilets.

“We were told there would be portaloos.”

The council is working on its concerns, and Liquor, Gaming and Fair Trading says it’s considering the toilet issue.

The council is a stakeholder in a masterplan process set up by the state government for locals to make suggestions about what should happen on the island. It’s due out this month for public consultation, with about $26m available for common infrastructure.

Ireland is hopeful more activity is about to occur on Tower’s lease.

He met with Agnew before Christmas and was told renegotiations are going on with the state government.

“Which obviously, we’re not a party to so we can only sit back and hope something happens because at this point, we’re all pretty frustrated,” he says.

“I think there’s some new plans afoot, but then again, there’s been new plans afoot in the past and nothing’s happened.”

Whatever is planned, Mercer says, consultation with the community will be key.

“Whoever builds on the island, they need to work cooperatively with the people,” he says. “And sometimes that’s seen as a weakness, not a strength.”

The first people that need to be consulted, Mercer says, are the Woppaburra, the island’s Indigenous people.

The last 17 members of the tribe were forcibly removed from the place they call Woppa in 1902 and split up.

In recent decades, they’ve been fighting for recognition and in late 2021, Native Title was granted to the Woppaburra over 13 islands.

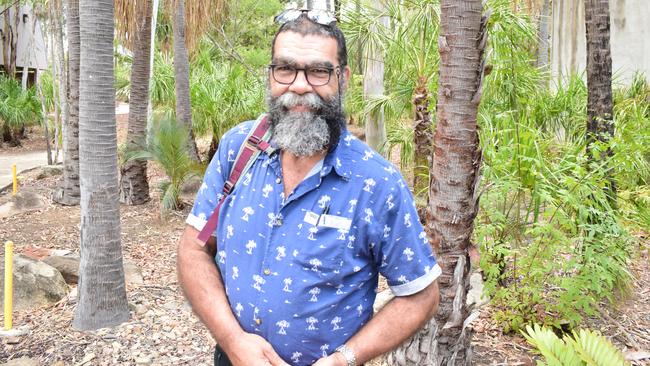

But Woppaburra Elder, Bob Muir, admits the tribe has mixed views about the future of the island and Tower’s role in it.

Some have “real bad blood about Tower” which he says harks back to 2007 when 173ha of island land was returned to them by the state.

Tower supported the land’s return but, soon after, flew about 40 Woppaburra to Brisbane and presented a proposal to pay them $11m for a perpetual lease over what had just been returned. Many were blindsided and angrily voted it down.

Tower’s current plan does not involve that land.

Muir, who worked in an office funded by Tower, backed the proposal but now says he’s glad it didn’t go ahead because no work has occurred.

But Woppaburra infighting remains. “I have to be upfront, our people, we have been divided ourselves,” he says.

One thing the Woppaburra do agree on, he says, is there should be no marina on shallow Putney Beach.

It’s long been a sticking point: some say it would boost visitors, stem beach erosion and help those with ambulatory issues.

Others, including Muir, say it’s a dugong feeding site, turtle nesting area and place of cultural heritage significance that should not be touched.

The Capricorn Conservation Council objects to a marina, too, but would consider a jetty.

Its coordinator, Sophie George, says the council is not anti-entrepreneur or development, it just wants a developer sympathetic to the island and able to work with the Woppaburra.

“Tower have had their chance and they’ve shown us that they cannot be environmentally responsible,” she says.

The CCC supports an eco-tourist resort on the existing site.

“People want nice amenities, a tourist centre to give people some environmental and cultural information, a nice place to stay on the island,” she says.

As for the derelict site: “We want it gone. For the love of god, get rid of it and someone take accountability and ownership and get that monstrosity off the island. It’s embarrassing.”

For now, shattered glass and broken beds litter the old resort, lantana grows and a twisted pile of timber and electrical wires sits decomposing on faded tennis courts.

No one misses the irony that in its heyday, Great Keppel was promoted as a great place to get wrecked.

It used to be funny. No one’s laughing anymore.