The untold story of Brisbane’s Holocaust heroes

Tales of extreme bravery, like that of Jacob and Klaasje van der Haar, who hid a Jewish baby and teen from the Nazis, will be preserved in Brisbane’s new Holocaust museum and education centre

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Watching elderly veterans’ wave as they drove past in Anzac parade after Anzac parade, their numbers dwindling year after year, Ingrid Bradford’s thoughts always turned to her beloved late grandparents.

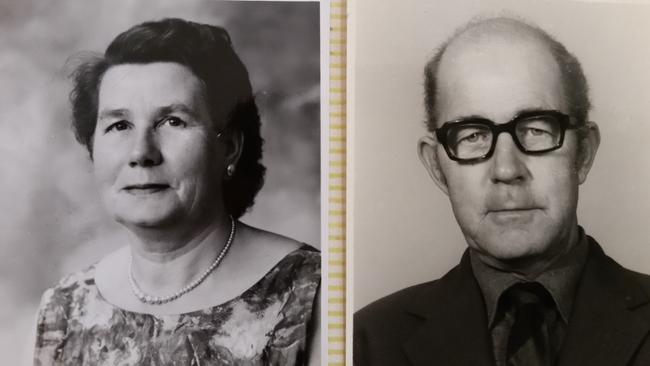

Her Oma and Opa, Klaasje and Jacob van der Haar, had been Brisbane residents more than 40 years when a letter came notifying the couple they were to be honoured for risking their lives to save a Jewish baby and teenage girl during the Holocaust.

Jacob had died by then and Klaasje, in her 90s, was too frail to travel to Sydney for the official ceremony.

The letter was put aside as family concentrated on caring for their beloved Oma, eventually to be forever reunited with her cherished husband.

Grief, then everyday life, swallowed time, the letter lost, the honour all but forgotten. Except on Anzac Day, when Bradford’s thoughts inevitably turned to the deadly risks her Dutch grandparents took and the mystery award they never received. It would take two years, countless emails and lots of determination before Bradford tracked down the details and, in an emotional ceremony, accepted a medal on her grandparents’ behalf, almost 20 years after the original letter was sent.

It’s been more than seven decades since World War II ended and the horrific discovery more than six million Jews had perished, yet stories like the van der Haars’ are still coming to light.

Now their bravery – and that of others like them – will be recorded forever in a Holocaust museum and education centre to be built in Brisbane, serving as a universal warning against racism, bigotry and hate.

The simple black and white photos – one of a woman and toddler embracing, the other of a seemingly traditional family standing outside their home – capture a moment not only of enduring love but also courageous resistance and profound humanity.

Dutch metal worker and father of three Jacob van der Haar was involved with the underground resistance during WWII, often holding secret meetings at his family’s small Hoogeveen home in German-occupied north-eastern Netherlands.

In the summer of 1942, when the deportation of local Jewish residents started, Benjamin and Gila Gokkes, of nearby Groningen, went into hiding rather than reporting for “work in the east”. Resistance members took their two-year-old son, Joseph, to a series of temporary addresses, until several months later, he was delivered to the home of Jacob and Klaasje van der Haar. Renamed Joop, the little boy was presented to the van der Haar children – Frits, Jack and Geertruida – and the outside world as a child whose father was working in Germany and whose mother was too ill to care for him. It did not take long for Joop to start calling Jacob and Klaasje “mama” and “papa”, the children his brothers and sister – they became family, as those photos attest.

Discovery meant almost certain death for everyone. When a nosy neighbour commented that Joop’s father never came to visit, a friend posing as the father started visiting twice a year. An escape plan was formulated with sympathetic neighbours and a lady in their street, also active in the resistance, warned of upcoming raids, allowing Joop to be whisked away to safety. Still, the message didn’t always come through in time – once Geertruida hid Joop in the attic until German collaborators left.

Around this time, Jacob was caught on the street without a pass. He’d been on his way to the doctor to renew a certificate saying he was too sick to work, but was instead imprisoned in a German work camp.

Jacob and another man from his street managed to escape during a bombing raid, making their way home under the cover of night. He was in hiding for about nine weeks.

In February 1945, a Jewish girl from Amsterdam, Sonja Peters, 18, was also taken into the van der Haar home, where she hid until Allied forces liberated the area in April that year. It was then Canadian soldiers happened to approach Geertruida on the street, asking for directions to the van der Haar house.

They had news of Benjamin and Gila, who had survived the war and were desperate to be reunited with their son.

As happy as the van der Haars were to see the Gokkes again, it was a traumatic reunion for all. Klaasje obtained a special train pass to be able to accompany Joseph home and see him settled with his parents. Her fourth child, born later that year, was named Joop for the little boy who stole her heart.

Joseph holidayed with the van der Haars every year until the Gokkes immigrated to Israel when he was 12, and stayed in touch even after the van der Haars migrated to Brisbane in 1956. Joseph, who became a husband and father, visited the family in Australia several times.

When Bradford ponders her childhood memories of Jacob and Klaasje, it is of raiding her Opa’s bean and strawberry patches, of her Oma making sandwiches of strawberries sprinkled with sugar; of school holidays spent with cousins at their Goodna home. It is of family and food and togetherness, always. Sailing from the Netherlands to Brisbane, the van der Haar family stayed in the Wacol Migrant Centre before moving into their own home. Jacob was a gardener at Wolston Park Hospital and Klaasje did some cleaning and housekeeping, while their children forged their onw lives.

“I don’t recall them talking much about the war, no, and mum was only a child, so what does she really recall and understand,’’ says Bradford, 53, the youngest daughter of Geertruida, 83, a retired school cleaner now living in Ormeau, and the late Willem Paerels, a boilermaker, who also migrated from Hoogeveen.

Jack is 87 and Frits, 85, while Joop – known as John in Australia – has died.

Bradford says the family always knew the couple had helped Jews during the war and an honour had been bestowed upon them, but it was only when her own sons, Sam, 26, and Jacob, 25, and nephew Liam, 27, returned from a European holiday exploring their heritage, asking questions, the search started in earnest.

“It was like finding a needle in a haystack, because we didn’t have the original letter. Where do we start? What do we do?’’ says Bradford, a Hervey Bay primary school teacher.

She emailed Dutch and Israeli embassies around the world, and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance centre in Israel.

Two weeks ago, at a private ceremony in Brisbane, Israeli ambassador to Australia Tibor Shalev Schlosser presented Bradford with the Righteous Among the Nations medal in formal recognition of the title awarded Jacob and Klaasje in May 2001.

One of Israel’s highest honours, the Righteous are non-Jews who risked their own life, freedom and safety to rescue a Jewish person from the threat of death or deportation without exacting financial or other reward. Recipients have to be nominated by a survivor, or through other documentation.

Joseph nominated Klaasje and Jacob and lived long enough to know they were honoured with the title. Daughter Inbal spoke at the Brisbane ceremony on her late father’s behalf, via video-conference from her Israel home, mother Shifra by her side.

The van der Haars were the 9341st recipients, in a list of 27,712 Righteous from around the world. Two or three such ceremonies are held in Australia annually.

“I don’t think I can explain how much it means to us as a family. We all tear up when we talk about it, and the realisation of what Oma and Opa did during that time, the risk they took,” says Bradford, whose older sister Karen McNevin, 55, lives in Townsville.

“If you were in their shoes, what would you have done? What they did was such a big risk and obviously shows their kindness, their empathy for these people.

“I know how important it is, I know what my grandparents did was very brave and courageous … but it’s only once you have your own children, that you think more about the history. Generations of today need to know about it.”

On Monday night, the Brisbane Synagogue will be lit up to mark the anniversary of Kristallnacht or Night of the Broken Glass, when rioting, looting and mass arrests across Germany, Austria and Sudetenland heralded the beginning of Nazi Germany’s Final Solution.

Only two months ago, the heritage-listed Margaret St building was defaced by a right-wing extremist group, who posted their actions on social media alleging Jews were responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s evidence that Brisbane’s Holocaust museum and education centre is needed more than ever, according to Jason Steinberg, vice-president of the Queensland Jewish Board of Deputies.

A total of $7.5m in federal, state and council funding has been pledged to establish the centre, a “dream come true” for Steinberg and his community who have been lobbying more than 10 years.

Since the museum was announced a month ago, the Board has been overwhelmed with support and people wanting to share their families’ wartime stories.

The centre will focus on Queensland’s Holocaust survivors and rescuers, and wartime migrants, and also acknowledge other genocides and showcase the state’s multicultural society. More than 50 Queensland teachers, who have travelled to Israel to complete the Gandel Holocaust Studies Program for Australian educators, will be incorporated into an education program.

“On lots of different levels, the stories of the Holocaust resonate today, just as they did two decades ago, or five decades ago, or just after the war,” says Steinberg, whose ancestors fled the pogroms of Tzarist Russia, via China, to Australia. “And they resonate because people living in society haven’t learnt the lessons, and racism, bigotry and hate still exist.”

An estimated 8000 Jewish people live in Queensland, and Australia has the largest per-capita Holocaust survivor population outside Israel.

“If people can be educated, particularly the younger generation, if they can learn about these stories, they’ll be able to understand the worst that can happen, so when they’re put in a situation, in a schoolyard or workplace, they’re in a position to feel confident and stand up (for people).”

Back home in Hervey Bay, Ingrid Bradford looks through photos of her Oma and Opa. “It’s just humanity; be nice to be people, help them if need be.” ■