‘People were crying out they couldn’t breathe’: Brisbane doctors on COVID frontline

Two Brisbane doctors have shared their difficult experiences treating sick COVID-19 patients, and explained the devastating effect the virus is having on the body.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was two months he will never forget.

Two months of unceasing, yet often futile treatment of New Yorkers stricken with COVID-19.

In March, New York was declared the epicentre of America’s COVID-19 crisis and in the city’s busiest emergency hospital department, Australian doctor Yemi Omotoso was in the thick of it.

Working on the frontline of the Lincoln Hospital in The Bronx, Omotoso was one of a team of doctors overrun with up to 100 COVID-19 patients presenting to emergency each day.

Some patients were dead on arrival. Others, despite receiving oxygen, cried out, frantic, as they struggled to breathe. Others, who had stopped breathing, were not able to be resuscitated as the risk of aerosolising and spreading the virus was deemed too dangerous.

‘I blamed myself’: Robin Bailey’s most candid interview yet

Queensland Ballet’s plea for help: ‘we need more blokes’

Omotoso was on shift when a female patient, assessed as less critical and placed in an observation area with oxygen, was seemingly well enough to go to the bathroom but collapsed from heart failure in the toilet cubicle.

But on what he says is his worst 12-hour emergency department shift, five critically ill patients were intubated – a tube put down their throat to assist their breathing – only to have five different patients die in the unit.

Why you should subscribe to The Courier Mail: https://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/courier-mail-subscription-offer-sign-up-for-the-latest-deal/news-story/27cd0ab6fd10f8987fb6fcdea60d9e70

That’s not accounting for what casualties there may have been in the other units of the hospital, let alone at other hospitals in the city. During the peak of the pandemic in New York in April, nearly 800 people were dying a day.

Omotoso, 33, who studied medicine at The University of Queensland, has worked at Lincoln Hospital as an emergency medicine resident physician since June 2018 and will finish his remaining post graduate training there over the next two years.

He hopes to never see shifts like that again. But he knows he might.

Speaking from his home in The Bronx, New York, Omotoso says there are currently far fewer cases in New York but he fears the danger is not over.

“The virus still exists and at my hospital we still see one, two, three cases every day. We need to be vigilant right now,’’ he says. “From mid March we were swamped with cases. People were dying in front of us – left, centre, right.

“Most people had respiratory distress. They can’t breathe and their oxygen levels are really low. Normal oxygen levels should be 96 to 100 per cent but some patients were as low as 55 per cent. We put people on oxygen tanks, lying next to each other, sharing a tank of oxygen.

“The oxygen is the only thing that is making them feel comfortable. In the severe cases, they are crying out that they can’t breathe.

“There are also silent hypoxics. They can be talking to you but their oxygen level is very low, so the cells in their body are not getting the oxygen they need. That’s why the organs in your body begin to fail.’’

Omotoso says that for many patients who were unable to breathe on their own, doctors had no choice but to intubate but this also presented problems.

“We noticed pretty early on that intubating was not necessarily in a patient’s best interests because they kept dying,’’ he says.

“We have to tell patients that if we help them to breathe by intubating them, there’s no guarantee they will come out of it.

“It’s hard. There’s only so much you can do.’’

Omotoso was born and raised in Lagos,

Nigeria, before moving to the US for tertiary study, completing an undergraduate university bachelor degree in biology from Columbia University in New York. He planned to return to Nigeria but when his parents and two younger brothers immigrated to Australia in 2007, he also moved here.

He lived in the town of Robinvale, in rural northwest Victoria, for a year working as a laboratory assistant at a food manufacturing company before being accepted to study medicine at UQ. After becoming an Australian citizen in 2014 and graduating medical school in 2015, Omotoso worked at Ipswich Hospital, west of Brisbane, as an intern.

All the while he was also having a long-distance relationship and travelling back and forth to the States (sometimes for less than 48 hours at a time) to see his American doctor girlfriend, Damilola, 31, who he met while studying in New York. They married in 2016.

Omotoso applied for his residency at Lincoln Hospital while he was working at Ipswich, desperate to be closer to his wife who works in Boston. Though it was the closest job he could find, the couple still live in different states, with Boston a four-hour drive away.

They have a 14-month-old son called Joel and Omotoso, who is also studying for a Master of Business Administration, visits every week.

He also visits Australia every year to see his family who all live in Perth – his mother, Bola, 56, is a nurse, his father Jose, 63, is a doctor who works for the prison system, brother David, 30, is a cyber security engineer and brother Segun, 28, is studying business.

“I do hope to come to Australia this year because my whole family is there,’’ Omotoso says.

“I’ll go to Perth to visit my family and I have friends in Brisbane who I go and see. My best friend is in Brisbane.

“I have two more years on my training at Lincoln and I still maintain my (medical) license in Australia. I do hope to return back home to Australia to work.”

Queensland infectious diseases consultant Dr Kylie Alcorn, 41, who finished her speciality training in early 2015, knew the chance of a global pandemic occurring during her lifetime was likely. But theory and practice are different beasts.

Based at the Gold Coast University Hospital, Alcorn says “we are all learning as we go”.

“This is the first time I’ve been involved in a pandemic,” she says.

“I thought I would go through a pandemic in my life because the last one was the Spanish flu in 1918. Unfortunately, we were due for one.

“But I don’t think I ever really thought it would happen to this magnitude.”

The pandemic has dramatically changed Alcorn’s job, effectively splitting it into two parts – her normal infectious disease management of patients and managing Gold Coast Health’s COVID-19 response. Tom Hanks and wife Rita Wilson were two high-profile COVID-19 patients at the hospital back in March but, as you would expect, Alcorn can’t comment on their case due to patient confidentiality.

Alcorn has been involved in setting up a virtual ward for COVID-19 patients who don’t need to be in hospital, as well as organising fever and screening clinics, and ensuring proper medical management of patients who may not have the virus. (“We need to remember it’s not all COVID,” she says).

“It’s really been a big learning curve. We’ve all had to adapt and learn new skills – IT stuff, organisational structures and management, communication skills and taking on more of a leadership role as well. There are so many things to cover.”

Alcorn, like all medical experts, is still learning about COVID-19.

What she does know is that the virus can have multiple serious effects on various organs of the body, affecting not only the lungs, but potentially the kidneys, brain, intestines, heart and blood vessels.

Aside from respiratory distress, patients can suffer from arrhythmia (improper beating of the heart) or the heart can become inflamed. Blood can become “thickened” making the patient more susceptible to clots.

“The reason COVID-19 has had such a big impact is because we are all non-immune. We have 100 per cent of our world not ready for this virus,” Alcorn says.

“But for more than 80 per cent of people who are infected with COVID-19, they will have a very mild illness.

“It’s different from the flu in that there is a higher rate of severe disease with COVID-19 – anywhere between six and 15 per cent of patients will have a severe illness. It has a higher mortality than influenza.”

Any longer term health effects of COVID-19 are as yet unknown. However, Alcorn says many viruses, such as Ross River fever, cause side effects of fatigue, and aches and pains, for many months, even years after the illness.

“The patients I have seen after their COVID, the vast majority have no problems,” Alcorn says. “There are really only a couple of people I have seen out of more than 200 people who have mild problems like fatigue.

“I have to tell them I don’t know when that is going to go away.”

In New York, Omotoso says he is now seeing patients, who contracted COVID-19 in March, still suffering adverse effects.

“We still don’t know the effects of the lung damage people may sustain,” he says.

“I’ve seen patients who have come in one or two months after they had the virus and they have residual chest pain or difficulty breathing. No one really knows the effect of it.

“And I know some frontline health workers have gone months and months with symptoms. They are debilitated, they cannot work, move, eat, they have lost weight. The effects of it are ongoing.”

How long the pandemic will last is also a great unknown.

There is also no guarantee of a vaccine and more information is needed to assess how long humans may be immune to the virus after recovering from it. Until then, there is no way of knowing when cases will begin to plateau.

“This is going to stay for the indefinite future and, really, who knows what our world is going to look like at the end of this? It will be a new normal, that’s for sure,” Alcorn says.

“If you think about (the terrorist attack) 9/11, our world was never the same after that. We had a new normal after 9/11. And I think how we live will be different after this pandemic too.

“Our kids are growing up not socialising, there is homeschooling, there is a lot of fear. On the flip side there is also a new community spirit and people are interacting in different ways.

“COVID-19 will continue to be an issue for the rest of the year at least, if not all of next year, until we get a very good vaccine and, of course, there’s no guarantee of that. There are so many unknowns.

“I look into the future with interest about how we will be at the end of it.”

Emerging from all the death and despair of a virus-ravaged New York, Omotoso has a clear message for his Australian home: this virus doesn’t discriminate; social distancing is the best defence we have; please take this seriously.

Omotoso says a team of residents and doctors at Lincoln Hospital is planning to publish research about how they handled the virus crisis and what was learned.

“People need to wear their masks, wash their hands and I cannot emphasise social distancing enough. It’s essential,’’ he says.

“Early on, in New York, there were many older people who died but there have been a lot of younger people too. Most of the patients I saw personally who died were aged 45 to 55.

“The virus stays in the air longer than people think. It can stay on people’s body surfaces and clothes. It’s not just droplets, it’s in the air.

“It spreads faster than people think.’’

Omotoso hopes another wave of virus doesn’t come to New York but believes the city is better prepared if it does.

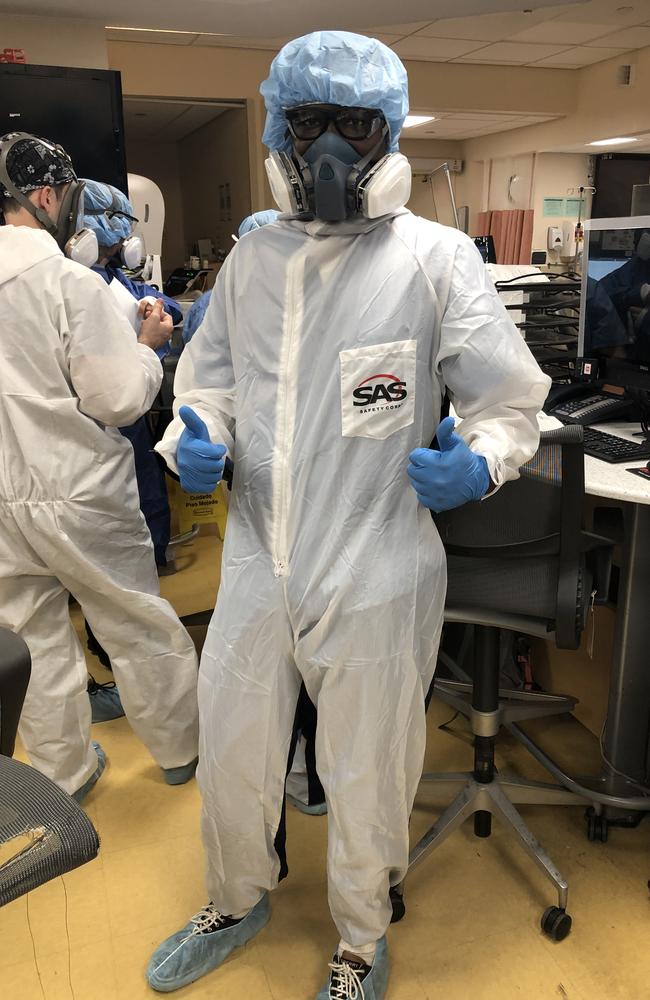

In the beginning of the first virus wave in New York, he says doctors were not even equipped with adequate personal protective equipment (PPE).

The only way doctors in his hospital received proper protective gear was when one of the senior doctors, in charge of disaster management, personally purchased PPE for more than 50 staff.

This, Omotoso believes, saved many doctors from falling ill, with just five of the 43 residents becoming sick and all of them since recovered.

The generous doctor was ultimately reimbursed by staff and a Go Fund Me page that was set up.

However underprepared the world was for COVID-19, hopefully valuable lessons have been learnt for whatever comes next.

“As doctors, I don’t want to say we were numb to all the loss of life but there was only so much we could feel,” Omotoso says.

“People died in front of us. We didn’t have time to grieve or dwell on what was happening. The next patient who couldn’t breathe was right around the corner.

“We were just physically exhausted, we were burnt out.

“When the next wave comes – if it does come to New York – we’ll be better prepared and I hope other people can learn from what happened to us.”