‘It’s a chasm of grief and sadness’: Lawrence Springborg reveals devastating loss of daughter

As he signals his return to the political limelight, former LNP leader Lawrence Springborg has opened up about more personal matters, including the tragic death in 2020 of his beautiful, bright daughter Megan, admitting “it’s not an easy thing, not at all”.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

About 15km east of Bundaberg, at Mon Repos beach, an annual odyssey takes place. Every January, hundreds of tiny, loggerhead turtles emerge from ping pong ball-shaped eggs to scurry by moonlight to the sea.

Flippers moving like egg beaters, the loggerheads swim for three days until they hitch a ride on the Eastern Australian Current all the way to the waters off Chile and Peru.

Eventually they will make the return trek to Australia’s coastal waters. Along the way they grow and mate until a handful of adult females lumber up the beach to lay their eggs very near to where they hatched almost 30 years earlier.

Such is the odyssey of the Mon Repos loggerhead, such is the pull of the place where they were born, such are the fantastic odds that bring them home again.

About 65km east of Goondiwindi, that thirsty Queensland border town hunkered beside New South Wales’s Boggabilla; past white, fairy flossed fields of cotton, and wheat silos standing guard over the Cunningham Highway, is the small town of Yelarbon.

Another 10km out of town, the bitumen turns to hard earth on a driveway winding its way past stubbly wheat fields, and the odd crow on a telegraph wire, to where Lawrence Springborg, former leader of the Liberal National Party (LNP) jumps down from the cabin of his New Holland 6080 tractor, hand outstretched in greeting.

Springborg. The Borg. The Borginator. The Father of the LNP. The Gentleman of George Street, now Mayor of Goondiwindi, having swum all the way home.

It’s fair to say that Springborg’s political career has been somewhat of an odyssey itself. Here follows a very potted history.

First winning the Southern Downs (then known as Carnavon) seat for the Nationals at just 21 years old, Springborg was the youngest MP elected to Queensland parliament, a record that still stands.

A country boy, he was cast as the shining hope of the post Bjelke-Petersen National Party, and would go on to have three stints as state Opposition leader (from 2003- 2006, 2008-2009, and 2015-2016).

After losing the 2004 and 2006 state elections to Labor’s Teflon-coated Peter Beattie, Springborg did not recontest the leadership, and was replaced by Jeff Seeney.

By 2008, the Borg was back, this time as the Father of the LNP, hell bent on making the union between the Libs and Nats official.

But the LNP lost the 2009 election, and Springborg did not contest the leadership, instead becoming deputy under John Paul Langbroek.

In 2012, he became a Minister in the short-lived, Campbell Newman-led LNP government, but when it lost the 2015 state election, Springborg once again became its leader.

In 2016, he narrowly lost a leadership challenge by Tim Nicholls, and announced his retirement from state parliament in December, 2016.

Then, in 2020, in a decision that had politicians from both sides of parliament scratching their heads in disbelief, the LNP removed him as a trustee of its executive, a move akin to firing a long-term and much-loved cast member from a popular soap opera.

All of which is to say that Springborg’s political journey has been not unlike that of the Mon Repos loggerhead. And, as he notes himself, casting his eyes over the rows of wheat stubble at his 810ha Yelarbon property, every bit as perilous.

“I’m exactly like one of those Mon Repos hatchlings that swims all the way to South America, navigates all of life’s challenges, fights off a few predators along the way, and then one day has this strong urge to come home. Thirty or so years later, it comes up in the same spot on the same beach it hatched all those years earlier,” Springborg smiles.

“That’s me and I don’t need GPS tracking or maps, either, I could find this place with my eyes shut.

“I think most people end up where they began. I think that the homecoming urge is so strong – it was for me – just to end up somewhere where I felt completely comfortable, where I’m made to feel welcome and at home.”

So why go back?

Why after being elected the (independent) Mayor of the region that raised him, where his family first arrived from Denmark in 1908, where he was born in the nearby Inglewood hospital, and where his family still owns and farms three properties – two at Yelarbon and one at Inglewood, spanning a collective 12,000ha – is Springborg dipping his toes back in the water?

Because, in a move that surprised no one in Queensland political circles, the LNP has invited Springborg back into the fold.

He is expected to return to its executive when the party holds its state convention in July, this time as its likely president.

More than 30 years after joining, Springborg is once again the shining hope of the party, its main chance, insiders say, capable of reuniting the bitter factions it insists it doesn’t have. The same insiders also say it took some wooing; Springborg, a little like a spurned lover wary of being burnt again, sought some guarantees and assurances from the party.

But ask Springborg about it, and it becomes apparent one of the reasons why the LNP want the man who is conversely both their founding father and prodigal son, back – he’s never been one to kiss and tell.

“Being on the executive as a trustee is a gift given and a gift taken, and if you believe in democracy that’s the way it goes,” he says in his signature slow and sonorous voice, so well known in the corridors of Queensland power.

“It (being removed from the executive) didn’t keep me awake at night at all, no, if democracy is a currency, then you have to accept every transaction.

“I have always kept away from being a partisan, political commentator, it’s not me.

“If I am elected president, and despite what you hear, it’s not at all a given, there are others who will put their hand up, but if I am, you won’t see me throwing my two cents in from the sidelines, no one is going to see me come July sprouting my opinions, you’re not going to sell me as an election night commentator.”

“Sometimes,” he continues in his rumbling timbre, “the hardest, but best thing to do is not say anything at all.”

What he will say about his generally considered in-the-bag presidency is this.

“What I would like to see is a functioning democracy benefit from a true contest of ideas, a place where people put personalities aside and focus on the good of all, focus on the end game, focus on the party, not the players, it’s not very complicated at all.”

But apart from being asked nicely, the other reason he’s getting back in the water is because the boy from the bush just can’t help it.

The Borg loves state politics.

The truth is, its pull is every bit as strong as that of his hometown. This time around, however, he’s found a way to have his CWA cake, and eat it.

Should he return to the LNP executive, Springborg will continue to be Mayor of Goondiwindi, “for as long as they’ll have me”.

He will stay on the family property with his wife Linda, tending to their wheat and barley crops, their cattle and sheep and the people of this region he knows so well.

He will travel to Brisbane only when necessary for state executive meetings and other party matters, and will continue to conduct a great deal of his business from the airconditioned cabin of his New Holland.

“Look, no hands!” Springborg says above the hum of his tractor, pulling its huge, combine planter at the back.

“Agriculture today is all about technology.

“This is hands-free, it’s set up with a telephone booster, I can take Zoom meetings, it has auto steering, it’s set up to go one way, then turn around at a given time. I can send emails from here, take conference calls and I can do all of this in airconditioning,” he grins.

“So unless I have to be present physically at a meeting or an event, I can do a lot of my work from here – I’ve just finished a teleconference on the inland rail,” and if he seems a little giddy at this brave, new world, it’s because he still remembers doing planting and harvesting as a boy on these very fields, come rain, hail or shine – and not in airconditioned comfort.

“You’d just be out there for hours, going round and round in circles, with the sun beating down on your back, or the rain pouring in under your shirt, you’d be up before school and back out again later.”

But while the technology might have changed, the hours haven’t.

Springborg is usually in the fields as soon as it’s light, before doing a full day’s work as mayor, then he has dinner, and if he’s not at an event, he’s back out again until about 11 o’clock at night.

“I don’t mind,” he says, “I’ve always enjoyed hard work, and I can’t let the farm work interfere with my role as mayor. I have to give the people of Goondiwindi and this region my all, because they’ve given so much to me from when the people of this district gave a young man a go all those years ago.

“And I love this job every single day I do it, even though being mayor is not something I thought I’d do when I retired from politics.”

The people of Goondiwindi are fond of Springborg, too, judging by the response he gets everywhere Qweekend goes with him.

“G’day, Lawrence,’’ they say on the main street, “Howyadoin’ Lawrence?” they say at the service station, “Good to see you, Lawrence,” they say at an art gallery opening in the evening.

It seems that everywhere he goes, at least in this part of the world, Lawrence Springborg is welcome.

Later that morning, down from the tractor, and from behind his mayoral desk in a dark suit and tie, Springborg describes his mayoral style as “approachable”.

“When I became mayor, at the first meeting I said: ‘You won’t find me on social media, you won’t see me on Instagram, but here’s my mobile phone number. Phone me if you’ve got a problem or, better yet, come in to see me’, and the nice thing is you can do that here.”

And they do phone him. They do drop in to see him. They do bail him up in the street to talk about stock prices, land parcels, rain gauges, mice plagues, tractors, school funds, births, deaths, marriages, and everything in between.

Springborg knows these people. And they him.

“When I first came home and people started saying I should consider being mayor, I’d ask ‘why?’ They’d say, ‘because you understand us’, and I suppose I do.

“And I guess it must be in my blood. My wife said to me when I retired, ‘You know it’s not out of your system’, but I truly thought it was.” Springborg chuckles.

“Well, like so many times in our marriage, she was right and I was wrong.

“Linda always said to me, ‘You probably need to do more than drive the tractor and chase sheep’.”

Linda Springborg has always kept – with her husband’s blessing – a low profile, a quiet supporter of her husband’s sometimes bruising years in state politics.

They met through one of her cousins in Brisbane’s Wacol, he was 20, she was 23, and they have been married for 32 years.

Those who know her say she is smart, kind, and a hard worker. Qweekend catches a glimpse of her on a quad bike rounding up the their small flock of recalcitrant goats, and while she raises her hand in a friendly greeting, she doesn’t stop to chat.

As far as political spouses go, her role has always been to keep the home fires burning in the bush, while her husband did battle in the city.

Had she been the premier’s spouse, this role would not have changed.

But that is not the way the cards fell for the couple, something Lawrence Springborg says he has “not a trace” of bitterness about.

It is true that had his fortunes been different, had he not been up against a particularly strong adversary in Beattie, Lawrence David Springborg may well have been this state’s leader.

It is true there were some perfect storms along the way – an infamous 2006 campaign interview springs to mind.

For the first time in a long time, it appeared that the coalition might be in with a chance of winning, or at least forcing Labor into a minority government.

This time around Dr Bruce Flegg was Springborg’s running partner, but at a press conference early in the campaign, neither man seemed to be able to answer who would be premier should they actually win, with Flegg finally offering it was a matter of “speculation”. It was generally agreed at the time that the LNP lost the election there and then.

The next day, The Courier-Mail gave a nod to the Bjelke-Petersen days with its headline: “Leader? Don’t you worry about that”. Today, all these years later, it still hurts, with Springborg sighing audibly when it’s brought up.

“Well it was terminal,” he says, “we just never recovered from it.”

He was also part of the infamous LNP reshuffle to make way for Newman, then lord mayor of Brisbane, but despite all of this, Springborg is, as ever, diplomatic in his summation.

“Here’s what I truly believe,” he says, “I had the privilege of serving my community for 10 terms, and I had the extraordinary privilege of being a member of parliament, and I had the privilege of helping to forge the LNP. I have never worried about what may have been, because it wasn’t.

“When I left state parliament, I left with gratitude, and I have zero bitterness. I have been disappointed by the actions of some, but never embittered, no, not for a second because I have always understood the difference between destiny and destination. Your destination is where you’d like to head, and your destiny is where you end up.”

As for Beattie, Springborg allows himself a long, low chuckle.

“Oh, he was so hard to beat, so hard. I admired a lot of people on both sides of the house, I worked with some really good people over the years, people who were robust and forthright in their views, but respected others, and Beattie was one of them.

“What an extraordinary politician he was. When I heard he retired, I rang him and congratulated him, and said all the best to you and Heather (Beattie’s wife) and I told him how hard it had been for me to get his measure.

“I said it was like throwing a blanket over smoke, that no matter how you held it, it would come out somewhere. There was no containing him. You’d think you’d done it, you’d think you had him, and out the smoke would come from the other side.”

Speaking from his home in Sydney where these days he sits on several NRL boards, Beattie offers that Springborg “would have made a very good premier”.

“You know, politics is all about timing, but he would have done a really good job as premier had it gone that way, because he is a very decent person. He is a very good person, his moral compass is very true, his family values are exceptional and he is a Queenslander to his bootstraps.

“He and I were adversaries, certainly, but I think we had a mutual respect. I think that’s missing from politics a bit these days from what I’ve seen. For Lawrence and I, there was no personal animosity. I like him very much.”

And here’s the thing about Lawrence Springborg; he is known on both sides of politics, in the city and in the bush, as a good man.

So when Linda and Lawrence Springborg faced an unspeakable tragedy, when they and their children Jens, 27, a firefighter, Laura, 24, a teacher, and Thomas, 22, an agribusiness student, lost their daughter and sister Megan, 27, last year, there were many arms to hold them.

Beautiful, bright Megan had been missing in Tasmania for several days when her body was found in late July, 2020. There were no suspicious circumstances.

From behind his desk at the Goondiwindi regional council, Springborg speaks quietly of his eldest daughter.

“Our family has always been very private about these things, and different people respond differently to them,” he says.

“We are very aware that there is not an insignificant number of Queenslanders who have been through what we have.

“This is a chasm of sadness and grief and loss that’s very wide and very difficult to get across, and so the support and encouragement of Queenslanders both here and elsewhere has been of great comfort to us.

“We lost Megan and she was the most wonderful young woman, and so we will navigate that as best we can.

“We have to remember, too, that we have three wonderful children who are still with us and they provide us with a lot of motivation to go on, but it’s not an easy thing, not at all.”

From behind his mayoral desk, Springborg bows his head. “I don’t know what else to say to it, I really don’t.”

Nobody would press him to do so.

And so Lawrence Springborg’s odyssey continues.

He carries the wounds of his journey deep beneath his hard shell, and he carries on.

He has returned home to where it all began and where it will continue, still tending to his family, his farms, and the good people of Goondiwindi. He is returning also, to the party he founded, with no regrets.

Well, perhaps one.

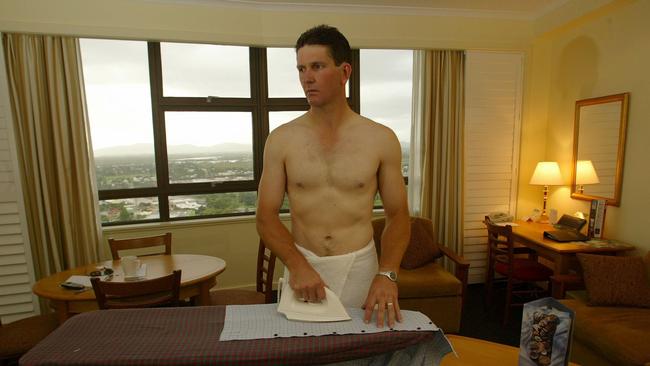

During the 2004 election campaign, Springborg was famously photographed ironing his shirt and wearing a towel around his waist. It caused quite the ruckus at the time and, Springborg says, haunts him to this day.

“I had an inkling you might bring that up,” he says.

“I was talked into it at the time, and honestly that is what life is like for a politician at campaign time, you are often ironing your own shirts and conducting business at the same time, but I got so much ribbing in town and at home.

“I think Linda sheltered me from most of it, I just wish all Queenslanders had been sheltered from it actually,” he chuckles.

“I would say to anyone seeking public office don’t take your shirt off for The Courier-Mail, because if you do, they’ll run it every time you do something.”

Springborg pauses, and runs his hand across his chin.

“You’re probably going to run it again for this article, aren’t you?” he asks, then nods resignedly when answered in the affirmative.

Lawrence Springborg. Good man. Good father. Good sport.

More Coverage

The smart way to keep up to date with your Courier-Mail news