‘It’s hard work’: Mitch Robinson’s partner opens up on difficult WAG life

Retiring Brisbane Lions star Mitch Robinson and fiance Emma MacNeill have revealed their struggles as a couple and how they managed to save their relationship.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

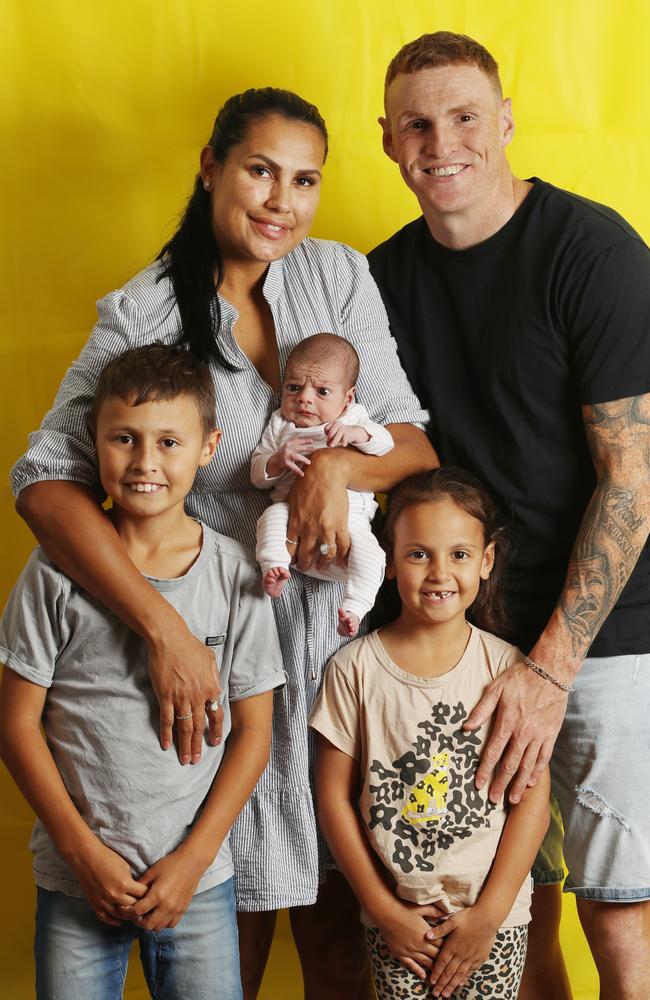

This tiny bundle of joy, all big, wide eyes and shock of black hair, cooing and gurgling contentedly in her mother’s arms, is Maali.

Her quiet, placid nature and a countenance many admirers compare to a wise, old soul have been an unexpected boon to besotted parents, artist and former radio personality and club QAFLW player Emma MacNeill and fiance, retiring Brisbane Lions player Mitch Robinson.

Adored by doting older brother Chance, 8, and sister Charli, 6, Maali completes their family in a way the couple, who have been together more than 12 years, didn’t know they needed. Fittingly named for the Nyoongar word for the black swan, the emblem of MacNeill’s home state of Western Australia and a bird symbolising an extreme, unexpected event that becomes explicable, the little cherub’s arrival marks the start of a new chapter for the family.

Something of a reset if you will, as the wild, rollercoaster years of combining Robinson’s premier football career with love and family – characterised by a grief, pace and pressure that nearly tore the couple apart – make way for a new chapter.

It’s a future somewhat shrouded in uncertainty and tinged with disappointment but one full of possibility, being embraced with optimism and hope.

Despite his shock retirement announcement on social media after his contract was not renewed and taking part in the motorcade of retired players at the September 24 AFL grand final between Geelong Cats and Sydney Swans, Robinson says he’s been approached by a number of clubs and is open to playing on next year.

“If it happens, it happens. It’s all up to if it makes sense for me and the family,’’ Robinson said recently.

At home in Norman Park in Brisbane’s eastern suburbs, MacNeill is simply focusing on selling the house that has been their refuge for the past seven years and getting her clan ready to spend a few months with family, first in Darwin then back across to West Australia.

“Mitchy and I are on the same page. If football is the next opportunity, we’ll 100 per cent take it. We see it as, if something comes your way, we’ll welcome it with open arms. If it doesn’t, it was definitely a great ride and we enjoyed every moment of it,’’ she says.

“We’re going to take time to adjust, to reconnect to culture and family. We’ve lived seven years without family support, so it will be really nice to be around them all again.’’

For as much as Maali is a welcome, beloved gift, for MacNeill being a third-time mum is no easier than being a first, particularly when dangerous assumptions were made in challenging pandemic times.

MacNeill does not consider herself a WAG.

After all, it wasn’t the Carlton football star she fell in love with all those years ago in Melbourne, but the crazy, red-headed country kid from Tassie.

And while she’s enjoyed the heady fun, glitz and opportunities being Robinson’s partner have offered, she describes herself as a simple Yamatji Martu girl from the bush. All she really wants and needs is him by her side, their kids happy and, perhaps one day, a patch of dirt to grow vegies, keep chickens and paint to her heart’s content.

“I’ve never met someone like Mitch before. Essentially, we figured out really quickly we were each other’s people,’’ says MacNeill, 33.

“It’s like we’d known each other our whole lives. He was the wild storm and I’m very calm, so it’s like we levelled each other out. But it hasn’t been smooth sailing. Anyone who wants to say dating football players is beautiful …,’’ her voice trails off. “It’s hard work. It’s not like a normal relationship. His job was our whole life.’’

Few people outside their inner circle know the couple separated for about six months not long after Charli was born, MacNeill and the kids staying in the family home while Robinson rented an apartment.

“We fell out of love with each other to be honest,’’ says MacNeill, who grew up and worked in the airline industry in Kununurra and Broome, dabbling in modelling after winning the Kimberley Girl competition in 2007.

She moved states to be closer to brother Carl, 36, who played for Hawthorn and Richmond, and his family. She also played Australian Rules, captaining Australia in the women’s division of the AFL International Cup in Sydney in 2011.

The couple had already supported each other through so much, including crippling grief after four miscarriages in the two years before nearly losing Chance, who was born in 2014, and Robinson’s delisting from Carlton after a career dogged by controversy.

Popular for his on-field kamikaze style, Robinson was fined $1000 for fighting in 2013 and $5000 in 2014 after lying about being involved in a pub brawl which resulted in his broken eye socket. Also, they had to build trust in the face of the “constant temptations’’ confronting sporting stars.

When the Brisbane Lions offered Robinson a two-year contract, the then family of three moved north in what was ultimately a winning move, the midfielder making changes on and off the field to be named joint winner of the team’s 2015 Merrett-Murray medal as Brisbane’s best and fairest along with Dayne Beams, Stefan Martin and Dayne Zorko.

At home, MacNeill was soon juggling two young children and billeting various first-year players while trying to pursue her own football and artistic ambitions. As well as painting customised boots for her fiance and the likes of Eddie Betts, Brad Hill, Dustin Martin and Justin Riewoldt, Indigenous Round guernseys and a cricket bat for Melbourne Renegades’ Dan Christian, MacNeill has designed logos, collaborated with Budgie Smugglers on a swimwear line and has canvases hanging in homes around the world.

Still, for the longest time, her only sense of identity was as “Mitch Robbo’s missus’’ and “mum’’.

“Our relationship is not perfect. He was playing seniors footy, I’m the 95 per cent parent and I do absolutely everything in this house, in return for a roof over my head and I never have to worry about if I can buy stuff for dinner,’’ says MacNeill.

“At the same time, it got to the point where it was not enough anymore, I needed my teammate and my partner. I felt like I had a roommate, not a partner.’’

MacNeill describes their separation as one of the hardest periods of her life, grieving and feeling like she’d failed herself and her kids, Chance particularly struggling to understand why Dad wasn’t home all the time.

It also triggered her own childhood feelings of grief, abandonment and bitterness from her parents’ divorce when she was four.

Raised by her Scottish dad Ed MacNeill and stepmum, Jen MacNeill, who joined the family when Emma was 12, she only saw mum Rebecca Peterson – who started a new family at the opposite end of the state – on school holidays.

“I’m a proud person, I didn’t want a break in my relationship, I didn’t want to share my kids with anyone else. Still, Robbo and I were good, saying if we did find another partner, we’d talk about it, want to meet them and be totally keen to co-parent,’’ says MacNeill.

“The love we have will always be there, you just get to the point in a relationship, like an

11-year relationship, we were well and truly at the point where you forget to add spark, it becomes a bit of a job. I also wanted to play footy but his job, his footy, is more important than me and then I’ve just got the kids. I felt like I didn’t have an identity.”

Somewhat ironically, she credits her teammates from Zillmere and later Wilston-Grange clubs as getting the ruckwoman through – forcing her out of bed, to keep moving forward, one step at a time. MacNeill was part of the 2018 Premiership-winning side, only retiring last year to move into a voluntary management and sponsorship role.

A broken air-conditioner on a sweltering day brought MacNeill and Robinson back together. She took the kids to stay in his spare room until it was fixed. He turned to her and said, ‘What are we doing, why aren’t we together?’

“I never got involved in his life and he never got involved in mine, we respected each other like that, but we literally got to the stage where we knew we didn’t want to be with other people, we knew we loved each other and wanted to be together. Our family was it,’’ smiles MacNeill, who shared the airwaves as a co-host with Jamie Dunn and Clay Cassar-Daley at 98.9FM Triple A Murri Country last year.

“It was the best thing we’ve ever done. It was a reset, literally. We just said, ‘Okay, this is what we need, what our children need, this is where we need to go from this point on.’’’

After a month-long, child-free escape to New Zealand and time taken for the family to find their new groove, Robinson surprised MacNeill by proposing a second time in front of their closest friends.

A new Paspaley Pearl engagement ring – a nod to her West Australian heritage – is being designed for her.

There’s no wedding date set and any ceremony would be a simple affair, likely just close family at the registry office followed by a casual celebration.

“We’ve got a funny thing in my culture where we say, you’ve been sung to someone. It basically means no matter what, I’ll always be your soulmate and you’ll always be mine. So, we’ve been given to each other and it’s so true. We’ve certainly had our ups and downs in the past 11 years, and we’ve always found a way to work through it and make things work.”

A mother is all MacNeill ever wanted to be, the one role she – a natural nurturer who started babysitting aged 10 – has always felt confident and comfortable fulfilling. Motherhood’s joys and heartaches, the bond between mother and child, inspire her very personal paintings.

Then Maali was born into a pandemic-shaken world and an ill-considered remark by a child health nurse almost stripped her bare.

Happy with their pigeon pair, Robinson and MacNeill were shocked by her pregnancy mid last year, then a “bit broken’’ when it was lost in the very early stages.

Hearts now open to the possibility of another child, they were thrilled with the news Maali was on her way.

Still, unlike the relatively smooth arrivals of Chance and Charli, this pregnancy was marred by awful morning sickness, the death of her beloved Granny Frances MacNeill and the stress around the future of Robinson’s career with the Brisbane Lions – not to mention the hectic pace of everyday family life. The nursery wasn’t even finished when Maali arrived by caesarean on May 12 at the Mater Hospital Brisbane.

Soon after they came home, MacNeill and Maali succumbed to a bad flu-like virus. Maali lost her appetite and could barely be tempted to feed, no matter what hold, position or trick MacNeill tried. No red flags were raised during Zoom appointments with doctors. Dressed practically in a tracksuit – “I looked ugly and a mess” – MacNeill took Maali to her six-week check-up with a local child health nurse, detailing the difficulties of the past few weeks.

“This nurse was looking at Maali, asking me, ‘Did you say you were Aboriginal?’ Yes.

‘I just want you to know that we correspond with the hospitals nearby and if I do need to contact child protection services, I don’t need to advise you. That’s our protocol’,” says MacNeill. “I could not believe it, that was the last thing I expected!

“We weighed Maali – she hadn’t specifically lost weight but she hadn’t put on a lot of weight, so she was still quite small. After explaining the feeds, I said Maali never cries and as soon as she makes any noise, I’m straight there trying to feed her.

“This nurse was like, ‘Yeah, she’s probably too lethargic to cry’ – as if she was some malnourished infant sitting in a dark room. I got in my car and just sobbed, and rang Mitchell.

“It made me feel awful. I’ve definitely been profiled a lot of my life and I’ve had the luxury of walking in both [Indigenous and white] worlds.’’

Worse, when MacNeill saw her GP soon after, he confirmed the nurse had rung and emailed him with her concerns. He advised her to start formula feeding – a blow for MacNeill who had always cherished the intimacy of breastfeeding for as long as possible.

“I was so distraught by this stage, I started second-guessing everything I was doing as a mum. If someone asked when I’d fed Maali last, I’d be like, is she hungry, we’ll just feed her just in case. My milk completely dried up, my hair started falling out and this woman – even though I don’t think she was being malicious – had me shitting myself that my kids were going to be taken away from me.”

MacNeill says while the manager of the clinic later apologised to her and Robinson, the incident highlighted what she sees as a lack of support for experienced mothers and the isolation affecting all mothers at a time when telehealth appointments dominated and parent groups fell by the wayside.

Art – along with the visible proof Maali is thriving and the support of Robinson and her GP – is helping MacNeill manage her anxiety and reclaim her confidence. Her oils, brushes and canvases come to life at night, when the house is asleep, though she is also working on digital art projects and fashion designs.

As well as considering playing with a new club, Robinson and MacNeill and are looking at collaborating on a golf clothing range while he’s forming commercial partnerships, hosting his Rob Vlogs YouTube channel, exploring the world of player management and considering an autobiography with “some home truths” and insights on navigating life with ADHD – a condition Chance was also recently diagnosed with.

“Often in the footy world Mitch’s been known as crazy or this tough nut on the field or a troublemaker, but they don’t realise this person, even at 33 years old, is still fighting his emotions and finding ways to understand himself. Still, to this day,’’ MacNeill says.

Right now, though, family is their focus with Maali at its centre.

“I really feel like she’s a healing baby, she’s got a very nurturing, calm presence about her,” MacNeill says.

“I just want to enjoy her, appreciate this moment, especially when I know that we’ve had struggles to get where we are.

“Like I said, the footy industry is not a pretty world and it’s a lot of extra work to keep yourself steering straight ahead. At the same time, it’s so rewarding and I appreciate the lifestyle we’ve had.”