‘I can’t walk to the top of the stairs’: Horror truth of ‘long COVID’

Despite ‘recovering’ from COVID-19, many survivors are now being hit with a debilitating, and often quite weird, collection of ailments that is stopping them from moving on with their lives.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

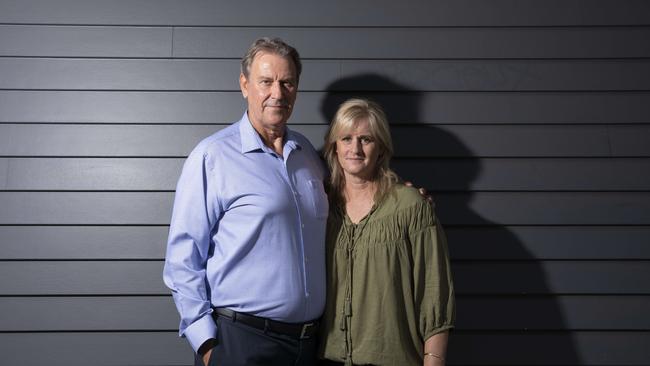

It used to be that Gary Macpherson could pull a golf cart around 18 holes without effort. He’d climb the six flights of stairs to his rooftop garden in inner-Brisbane’s Newstead, no puffing required. He’d eat and drink what he liked.

That was before he keeled over in the emergency department of the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital on March 30 last year, his body in the early stages of battling COVID-19.

Before he spent six weeks in intensive care, most of that in an induced coma, as an army of medical professionals kept him alive.

There were days his family was told to prepare for the worst.

Macpherson knew recovery after a long stint in ICU would take time.

The then-62 year old gritted his teeth through the painful rehab for his wasted muscles.

He slept for most of the day in the first months back home, returning to work as a software salesman in September, and even then only in the mornings.

But it’s been almost a year now and exertion leaves him short of breath.

His kidney function has not returned to its pre-COVID healthy condition. Macpherson’s kidney function test score used to be about 80 per cent (average for his age); today it’s at a concerning 40.

Every meal now has to be carefully considered – the protein weighed so as to not exceed his 90g limit. His beer choices are of the non-alcoholic kind.

“The renal stuff is clear and in front of my eyes,” says Macpherson, who until COVID-19 had never been admitted to hospital.

“They say kidneys don’t heal themselves. Once they’re buggered up, they’re buggered. But I don’t know what has happened to my heart.

“I don’t know what’s happened on a cellular level to my lungs.”

Macpherson is a long hauler, one of millions of people around the world who have endured, or are enduring, what has been dubbed Long COVID.

It’s a debilitating, often quite weird, collection of ailments varying between patients, but it can include fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, headache, joint pain, reduced lung capacity, tingling sensations, loss of smell and taste, dizziness, depression, hair loss, sleep apnoea and rashes.

Some recover after a month; others have lived with their symptoms for more than a year.

It’s feared permanent damage may be done.

Scientists are growing increasingly alarmed about just what is going on – silently, often undetected – in the heart, brain, kidneys and lungs of former COVID-19 patients.

Post-viral illness is not new; people can take weeks to recover from influenza and many who suffer the once-maligned chronic fatigue syndrome report its onset after battling a virus.

But the numbers of those afflicted by Long COVID are huge.

It could be “the pandemic on the pandemic”, according to Dr Gail Carson, the head of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium.

Dr Anthony Fauci, the chief medical adviser to the US president, estimates more than 10 per cent of COVID-19 patients will develop what is also called post-acute COVID syndrome, while Professor Danny Altmann, from Imperial College London, says it could be as high as 20 per cent.

The number of COVID cases globally is 110 million, so at 10 per cent, that’s 11 million people.

Already, post-COVID clinics are being established in hard-hit cities.

Don’t think it’s only those who were severely ill, like Macpherson, who suffer this ongoing syndrome.

Some hospitals and clinics report the majority of those unable to fully recover from their brush with the SARS-CoV-2 virus had mild symptoms that did not require hospitalisation.

Don’t think it’s only older people who battle to recover, either.

Many young people are reporting far worse ongoing symptoms than the sniffle and headache they had with the virus.

Social media pages set up by long haulers are filled with the stories of once active, fit, young people now laid up in bed or unable to work because they can’t think clearly.

A study of young, low-risk patients in the UK found that 66 per cent had impairments in one or more organs four months after their initial infection.

About 15 per cent of Ohio State University’s college athletes who had COVID-19 now have myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle.

Answers are being sought. But as Macpherson’s wife, Shelly Hillis, 52, was told many times during their ordeal, COVID-19 threw the medical world into “uncharted territory”.

Long COVID, with its multifaceted, hard-to-define nature, could prove even more difficult for science to navigate.

Macpherson is doing his bit. He is part of a number of studies being conducted in Queensland aimed at adding to the collective knowledge about COVID-19 and Long COVID. His son, Austin Cornish, 22, is also participating.

Cornish arrived home from New York in March last year as cases surged in the US city, the performer’s dream of making it big on Broadway smashed.

He had no idea when he boarded the plane home that he had COVID-19.

Asymptomatic, he enjoyed family gatherings, passing the virus not just to Macpherson but to Hillis, brother Glen

Macpherson, 40, and sister Sarah Macpherson, 25. He still battles guilt that his father almost died and may never fully recover.

For the “Brady Bunch” Macpherson clan, this is personal.

For scientists and clinicians in Queensland, it’s a professional challenge on a global scale.

It was a mild case of COVID-19 that struck the young scientist that Associate Professor Tony White had mentored through her PhD.

The woman in her thirties caught it in Germany, where she went to do a postdoc – an exciting time of study and adventure. But a wander through the Black Forest will have to wait.

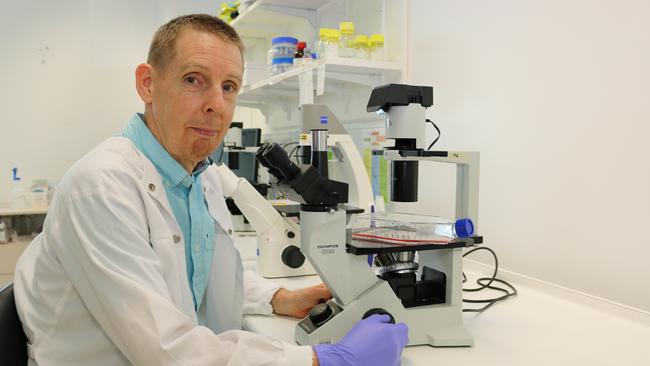

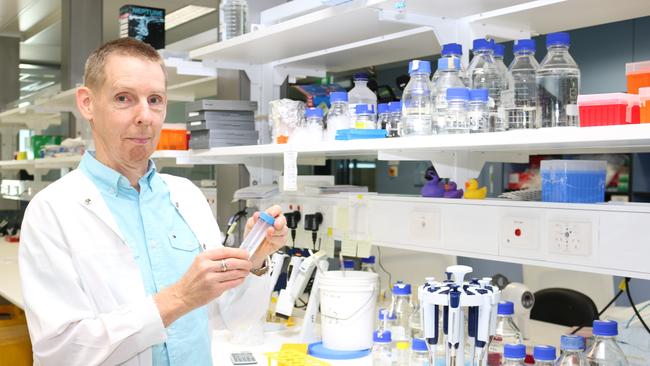

“She’s a young, very active person and now she can’t get out of bed,” says White, the group leader of neurodegenerative disease research at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. Chronic viral fatigue has taken over.

“The brain is saying that the muscles can’t work and, actually, they can, but if your brain is telling you that you can’t do something, then you just won’t do it,” White says.

“You can’t just ignore what your brain is telling you.”

He urges young people to take COVID-19 seriously.

No one knows the long-term effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. But in White’s field of expertise – the brain – “it looks very worrying”.

“There’s a lot of concern about what the long-term impacts of the disease are, not only in terms of continuing effects on the brain for those we know are affected but potentially, there may be latent effects that show up many years down the track,” he says.

It’s an unfolding mystery but the number of scientists and clinicians delving into the secrets of COVID-19, including Long COVID, is phenomenal.

By one count, there were 200,000 studies published by the end of last year.

We’ve learned a lot since the scourge began sweeping the world.

Intensive care specialist Professor John Fraser well recalls the early days, when up to 300 ICU specialists from around the globe would join a regular Critical Care Consortium hook-up – “almost a medical confessional” – to lay bare their shortcomings in dealing with this virus. “People who were experts before COVID were brave enough to say, ‘I’m not sure how to deal with this’,” says Fraser, who has key intensive care roles at Prince Charles Hospital, St Andrew’s War Memorial Hospital and the University of Queensland.

Today, survival rates in intensive care are vastly improved.

Some of that can be attributed to the knowledge gained through the consortium, established by Fraser and colleagues as an early warning system for the Asia-Pacific.

It has grown to be the biggest clinical COVID-19 study in the world – with about 400 ICUs and 55 countries contributing data.

Patient data is fed into a specially built IBM system at UQ, which uses artificial intelligence to create predictive models to guide treatment, depending on patient age, symptoms and pre-existing conditions.

Now there’s a spin-off: Along with the US’s Johns Hopkins University, the consortium is using its database to investigate Long COVID.

“Because of this huge amount of data from acute admission, we are starting a long-term study to follow them up post-discharge,” Fraser says.

“We’re developing an app where we can assess them at home.

“We can see how their brain function is working by doing a set of tasks on a mobile phone or iPad. We can see how far they can walk (in weekly or monthly intervals).”

Queensland scientists are heeding the call on Long COVID, too, keen to chart those uncharted waters.

White and QIMR Berghofer colleagues associate professors Corey Smith and James Hudson, along with the University of Queensland’s Dr Kirsty Short, are leading the locally based search for answers, specifically in the heart, brain and immune system.

White’s team is concentrating on the effect COVID-19 has on the blood-brain barrier, a tightly regulated layer of cells that protects the brain from what’s happening in the rest of the body. “We understand from the few studies that have been done (via autopsies) that the virus can infect this barrier,” he says.

“What we don’t know fully is what’s causing that brain impact; whether it’s the virus getting into the brain or whether it’s the body responding to the virus and then … changing the way the brain functions.”

At the acute stage of COVID-19, neurological symptoms can range from delirium, to an inability to walk, to brain fog.

Studies show 30 per cent of patients – 50 per cent if they have severe disease – suffer from neuro-COVID.

Just who will have ongoing problems once the infection has passed, and for how long, is undetermined.

White’s work will uncover more by using cell models of the brain and infecting them with the virus.

The goal is to test drugs – existing or those in development – that can prevent inflammation at the barrier, as well as prevent infection in the brain. Identifying biomarkers in the blood will allow doctors to determine who is at risk.

The vaccine roll-out is not a panacea.

“Immunisation isn’t going to change the fact that we need to be able to treat already-infected people that may have outcomes years, decades down the track,” White says.

“But even as the virus goes on and infects people who have had the vaccine, they still get the virus. They may not get serious disease but they’ll still get an infection that could potentially get into the brain.”

This unpalatable truth that the virus – and its variants – will linger among us despite the vaccines is part of what is driving Smith’s QIMR Berghofer immunology team in its search for T-cell immunotherapies to augment the vaccines.

“What’s going to be interesting as the vaccines roll out is, is it going to control everything really, really well? Hopefully it does,” Smith says.

“But we still need to be thinking about other treatments and other drugs, particularly in people who don’t make good immune responses.”

His team is in the process of inviting back 60 patients to take more blood as part of their investigation into the immune response to COVID-19 and the bid to develop immunotherapies. Macpherson and Cornish are among them. Hillis signed them up.

“If we could be a part of it, we might get more knowledge,” she says.

Let’s take a look at what we do know about the immune system and how Long COVID is likely to be unleashed.

We get COVID-19 when the SARS-CoV-2 virus penetrates our cells via the ACE2 receptor, a protein found abundantly in the lungs.

But ACE2 is also in the heart, the kidney, the bladder, pancreas, nose, eye and brain.

“What’s still not clear is everywhere the virus goes in the body,” Smith says.

“The lung is where most of the virus is but it’s not the only site of virus. So someone who has sleep apnoea (which Macpherson developed after contracting COVID-19 – he now uses a CPAP machine), is that because that’s the location of the virus and that’s where it does the damage?”

Some viruses, such as Epstein-Barr – which causes glandular fever – stay in the body.

Could SARS-CoV-2 stay in some sites and trigger a prolonged or recurring illness?

It’s a theory.

The more widely held theory is that Long COVID sufferers are dealing with an ongoing immune response – a debilitating, inflammatory hangover from what is called a “cytokine storm”.

It works like this. Humans are born with an innate immunity, as well as an adaptive immunity that ramps up when a new virus, such as SARS-CoV-2, hits us.

Adaptive immunity is made up of B-cells, which create antibodies – the focus of all the COVID-19 vaccines currently available – and T-cells.

It’s T-cells that Smith’s team works with to create immunotherapies.

When a virus attacks, the immune cells of our innate system get to work, “pumping out these inflammatory molecules called cytokines”.

They tell the body there’s something wrong and call in more troops.

“That then attracts all other parts of the immune system to help,” Smith says.

If everything works well, the inflammation is short-lived, the infection beaten and health returned.

“But the problem is, if you’ve got too much, it starts to cause damage,” Smith says.

This is the cytokine storm. The over-the-top, inflammatory response can cause severe illness, such as sepsis (which Macpherson suffered – the cause unclear), organ damage and blood supply starvation to tissues and organs.

This phenomenon in COVID-19 patients is well documented, with the immunosuppressant steroid dexamethasone emerging as the most effective existing drug to calm it down.

It was part of the cocktail of drugs used on former US president Donald Trump.

Ongoing inflammation – where the body’s immune response is still on high alert – is a strong contender to explain Long COVID in those who were severely ill with the disease.

It can cause lasting damage. But it is less convincing for those who had milder symptoms.

“So, people will start to look at, ‘Is it people’s genetics that influence these things?’,” Smith says.

“It doesn’t look like (Long COVID) is related to how severe the disease is, so are there other factors, like genetics, that play a role.”

But he warns: “Sometimes those things are hard to find.”

Plus, Smith adds, given the multiplicity of symptoms, Long COVID may have more than one cause.

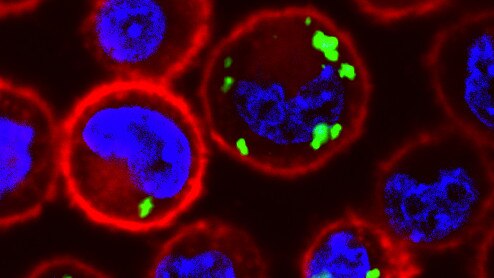

They are tiny - miniature, beating hearts created in a lab - but this cellular wizardry has helped their developer, James Hudson, zero in on the biology underpinning heart problems in COVID-19 patients.

Hudson’s team creates “heart organoids” that mimic what happens in the body.

By exposing the organoids to inflammatory factors known to drive immune responses, along with other hi-tech techniques, his cardiac bioengineering group has identified key proteins responsible for causing diastolic dysfunction in the hearts of COVID-19 sufferers.

His paper will be published soon.

“Our publication will be the first to show all these inflammatory effects on the heart and how it causes dysfunction,” Hudson says.

Diastolic dysfunction is when the heart has trouble relaxing between beats and “it’s the form being described the most in COVID-19 patients”.

It can lead to diastolic heart failure, a serious condition.

Some people with diastolic dysfunction have no symptoms; others suffer shortness of breath after mild exertion and difficulty breathing.

These are symptoms reported by Long COVID sufferers.

How many COVID-19 patients have been recorded to have heart dysfunction?

The research is daunting: two-thirds. And those figures come from hospitalised patients.

It’s unclear what’s happened in the hearts of those who did not go to hospital.

“In 15 years’ time, they could start getting heart failure because they’ve had this underlying dysfunction,” Hudson says.

“They may become insulin resistant or have diabetes, and that could exacerbate it later in life. But do these people fully recover a year later? We don’t know.”

The good news is Hudson has identified biomarkers that can be looked for to determine if a patient is at risk.

And there are drugs that could be used to prevent – or reverse – the problem.

In fact, as a sign of how world leading this research is, the Canadian company Resverlogix, which manufactures one of the drugs, apabetalone, has just announced it is using the findings of Hudson’s team to expand its trials of apabetalone in COVID-19 patients.

Across the river at the University of Queensland, Dr Kirsty Short and her team are looking at the long-term cardiovascular complications of COVID-19, particularly as it relates to Type 2 diabetics.

Diabetes is a risk factor for severe COVID-19, along with factors such as older age and obesity.

The UQ team is a world leader in studying viral infections and diabetes, and is looking for markers of cardiovascular stress in the blood of diabetics and non-diabetics.

Already, from the first round of blood sampling, results were surprising.

Every diabetic in the 70-strong study showed an elevation in these markers. More surprisingly, the markers were elevated in 80 per cent of non-diabetics.

“It’s not like these patients are going to fall over dead of a heart attack but it’s a biological indication that there is, or has been, some form of cardiovascular stress,” Short says.

A patient may not have felt any change to the heart but “it’s an indication the heart has had to undergo something it normally wouldn’t”.

The question is, do these markers stay elevated or return to normal? This should become clearer with ongoing testing of the study groups’ bloods. (Macpherson and Cornish are part of this study and Short is keen to enlist more patients.)

“If it stays elevated in a subset of patients, we can look at that and say, ‘What is it about these patients? Is it that they all have diabetes? Did they all have severe COVID or mild COVID?’ We can really delve into the ‘who is at risk’ question,” Short says.

“Maybe diabetes doesn’t make a difference at all. Maybe everybody who’s had SARS-CoV-2 should be monitored for cardiovascular complications.”

She is “pretty convinced” that the array of symptoms of Long COVID – she’s spoken to a sufferer living with the horror of all food smelling like rancid meat – is a result of the inflammatory response to the virus, not the virus itself.

“If you have chronic, long-term inflammation, that causes consequences – things like cardiovascular problems, like brain fog,” Short says.

“It could cause muscle ache and fatigue.”

Her lab is working on ways to leave enough of the immune response intact to control the virus, but to dampen the negative effects of that response.

“So that you’re not getting that tissue damage and that out-of-control inflammation,” Short says.

“It’s a very, very delicate balancing act; it is difficult to do.”

For now, Short’s advice is to do all we can to avoid SARS-CoV-2.

“You might have a mild, asymptomatic infection, but who knows long term?” she says.

“You want to do everything in your power not to get this. And right now, that’s vaccination.”

In the days his life hung in the balance, on a ventilator and in a coma, a CT scan was done of Gary Macpherson’s lungs. A good scan of the lungs would be black. Macpherson’s scan was a whiteout.

“It looked like I’d been a chain smoker for 100 years,” he says.

Recent scans have shown that, apart from some scarring at the base of one lung, the lungs are normal. Respiratory tests are much better.

“But in reality, if I walk up two flights of stairs, I’m out of breath at the top,” Macpherson says.

“If I walk up to the rooftop from the 10th floor to the 16th floor, I’m absolutely stuffed.”

The mystery of Long COVID has Macpherson undergoing a range of follow-up tests, consulting dietitians, on alert for symptoms.

It’s frustrating to him that right now, specialists only have diagnostic guides that have been around for decades.

“The doctors’ ready reckoners for dealing with lung and kidney and heart disease are looking at a lifetime of neglect, misuse or injury; mine happened in 48 or 72 hours,” he says.

“They don’t work for COVID-19. That’s why they say, ‘We don’t know’.

“They say, ‘We don’t know the long-term things that are happening. We can’t tell you what happens two years after people get it because it’s not been here’.”

An uncertain future.

But one thing is clear: while there is much scientists don’t know about Long COVID, they know it is real. And the hunt for answers has begun.