THE morning sun streams through a thick green canopy of leaves to wash over Billy Hedderman and his shining family in their bayside backyard. Hedderman is lying on his back, relaxing for a family photograph while his wife Rita tries to corral their two small daughters Lara, 2, and Isabel, 9 months. The family’s small Scottish terrier Ozzie wants in as well.

This slice of suburban tranquillity is at odds with Hedderman’s training as an elite combat officer, serving with the Irish and Australian armies on deployments in Bosnia, Chad and the Middle East. The tall, lean 36-year-old knows how to use all manner of guns and explosive devices and has done close to 400 parachute jumps, many times freefalling out of planes at night into dubious dropzones.

He is also an expert at staying cool in a crisis.

“We’re a pretty chilled little family,” Hedderman says.

“I’ve had a lot of adventure in my life but now I’m just dreaming about getting a beautiful Queenslander house and sitting on the porch, relaxing with my wife and children. That’s the end game for us.”

Five years ago Hedderman was on his back in Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital with a much different view of his future.

He recalls waking one morning to the sight of the hospital ceiling and in that first blissful second forgetting that he was an incomplete quadriplegic. As his eyes fluttered open, Rita pressed down on the remote control switch for his bed, lifting his inert form “semi-upright Frankenstein -style,” as he describes it, so he could fix his gaze on a printed poem hanging from the bottom of the hospital room’s TV screen.

The poem was Invictus, written in 1875 by William Ernest Henley.

Every day as Hedderman contemplated the accident that almost killed him, he would read Henley’s verses, reminding himself that while he had been “bloodied”, he remained “unbowed”.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Though paralysed from the neck down, Hedderman was still in control of his thoughts. The army captain told himself that he was still captain of his soul and while tough times would pass, the hardiness of his resolve would endure.

On the last day of 2014, having spent their first Christmas in Australia, Hedderman and Rita loaded up their little Toyota Yaris with Ozzie and a picnic hamper and headed from Brisbane to Caloundra for a day of sun, surf and sand.

They had been living in northside Mitchelton for just three months, having left behind the cold of the Irish winter and its decaying economy. Hedderman had transferred to the Australian Army and their life in a smart home near Hedderman’s base at Enoggera’s Gallipoli Barracks was one of new friends and backyard barbecues in what he calls “a world of eternal sunshine”.

The couple had been arguing about household finances that morning but on the drive north Rita turned down the volume of the ’90s dance music playing on the CD and the couple had what Hedderman calls a “long, lovely discussion” about the joy that the New Year could bring. “I glanced back at Ozzie on the back seat,” Hedderman says, “but he just raised his eyebrows.”

At Kings Beach, the couple plonked down their blanket and Hedderman hit the surf, riding waves on his bodyboard for 30 minutes. The couple were due to meet friends in Brisbane that evening to ring in the New Year, so after lunch and a walk for Ozzie, Hedderman told Rita that he was going back for just one more dip with the bodyboard.

“I was so genuinely happy with life that I felt I had to share it with my family in Ireland, and maybe rub it in a little,” he says. “So I made a quick video, showing how great life was at the beach, and posted it off to my family on our WhatsApp group before heading down to the water.”

He set up for a final wave and as it came closer he could feel it was going to be bigger and stronger than those before.

He turned and faced the shore. The wave crested just behind him and he could feel it pulling him up and backwards. His hips were lifted over his core. The top of the bodyboard caught in the water and the board flipped out from under him so that he was propelled forward and downward through the violent momentum of the wave. He felt a strong, hard thud as his head hit the sand.

Although his mind was hazy, he knew he needed to stand. But he couldn’t move. Dazed and confused, he realised that he was drowning.

Hedderman grew up just outside the village of Watergrasshill in County Cork. A “super-competitive sports-playing teenager”, he undertook officer training in the Irish Army straight out of school just after the 9/11 attacks in the US had put the world on tenterhooks.

He hated the first few days at the Curragh Camp in County Kildare, a lonely dorm full of strangers, but while he briefly thought about going home, he recalled all those rugby matches when he kept trying his heart out until the final whistle no matter how lopsided the score against him.

So it was also during the gruelling physical and mental struggles he then undertook to qualify for Ireland’s elite Army Ranger Wing: speed hikes up mountains carrying water and weapons, abseiling, leaping off bridges, being blindfolded and punched to replicate being tortured.

All those hardships taught him to push on in the face of adversity.

Rita was sitting with Ozzie on a grassed area at the back of Kings Beach when someone ran up to her and said “your husband’s been hurt’’.

She left Ozzie with a helpful stranger and ran across the sand to where he was lying, helpless in the arms of a lifeguard.

A teenager who had been bodyboarding near Hedderman had lifted his face out of the water so he could breathe. The sun was shining so brightly in Hedderman’s burning eyes that all he could see around him were dark silhouettes.

Then he heard Rita’s voice, a voice he had first heard when they were both 20 and met on a double date at a pub in Cork. Hearing her voice now, as his body lost all feeling, reassured him that everything would be OK.

“Billy couldn’t really talk,” Rita says. “I knew he was alive but that it was very serious.

“An ambulance came and we had a minute then to talk and gain a bit of clarity and to take stock of what was happening.” The ambulance took Hedderman to Nambour Hospital where he was told that he would then be flown by helicopter to Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital, which had a dedicated spinal injuries unit. Even amid his trauma Hedderman remembered the last time he had been on a chopper, fast roping from it during his time in the Special Forces.

Rita held a telephone against his ear so that, doped up with painkillers and in a faint voice, he could tell his family back in Ireland what had happened.

“Oh hey Reet,” he then said as an afterthought, turning his vacant eyes towards his wife, “Happy New Year”.

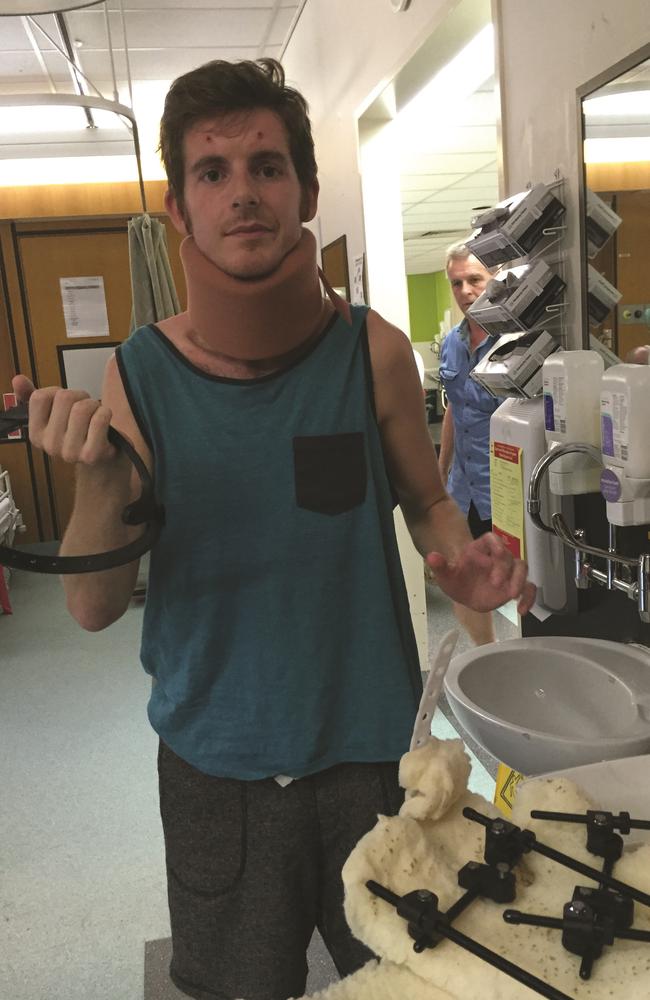

On the first day of 2015, Dr Kate Campbell, a spinal surgeon at Princess Alexandra, told Hedderman that his neck had been fractured and recommended that instead of surgery he should be fitted with a halo brace and chest vest to lock the neck in place while the fractures were healing.

The halo brace involved screwing two pins into his forehead and one behind each ear and attaching them to a chest vest to keep everything stable. For weeks he then underwent the indignity of sucking his food through a straw, the frustration and sleeplessness of being confined

to bed, the indignities of catheters and soiled bedclothes.

He was not afraid, he says, just glad to be alive and convinced he was going to get better, even though he wondered constantly if he would ever walk again or if his penis would still function when the treatment was over. The notion of one day having children seemed remote.

There was some good news, though.

“Spinal injuries are like an avalanche on a motorway,” he says. “Some avalanches block the motorway completely so nothing can get through but while my spinal cord had been severely damaged it was not completely severed.”

There was the chance of regaining at least some movement, so Hedderman decided that the gap between what he could get back and what he would get back now rested solely on his determination. He lost more than 20kg from his 80kg frame while confined to bed but, frail and weak, he promised Rita that he would literally get back on his feet soon.

Friends and family arrived to help, some from Ireland, some from around Australia. Soldiers at Enoggera’s 6th Battalion – 6RAR – did all sorts of chores around his home even though he had only known them a few weeks. He even liked their dark humour – the way they changed the Irishman’s nickname from “Spud” to “Mashed Potato” to fire him up.

He underwent extensive physiotherapy as the nursing staff challenged him. He was put through painful exercises to reduce the rigidity in his hands and to stimulate movement in his legs. After a few weeks he could bend his knee just a little, though trying to raise his leg off the mattress was an ordeal.

Gradually, though, with a lot of exercise and trial runs, he could stand, briefly, by the end of the month, even though his hips, knees and lower back all appeared ready to collapse.

After standing up four times in one day he promised to make it six on the next.

“The following week I took my first incredibly wobbly single forward step,” he says.

“It was tiring and I was aching all over. It felt like at any second I could just crumble forward or backwards. But I did it and while I was always grateful for any improvements in my condition I was never satisfied. I kept pushing.”

By the end of February, still in the halo brace, he was allowed home for a weekend, to sleep in his own bed and to drink beers in his favourite armchair, even if someone else had to open and hold the bottles. Simple chores such as brushing his teeth were now laborious dilemmas but nothing he couldn’t solve with Rita’s support.

“Rita was super strong for me,” Hedderman says. “She knew the way to help me most was enabling me, rather than doing it for me. If I was trying to pick something up she wouldn’t pick it up and hand it to me, but she would make it easier for me to pick it up myself. That showed real emotional intelligence and restraint and made me work harder to do things on my own.”

He began dexterity exercises, fishing for coins in bowls of rice, and writing lines, like school punishment, with a splint so he could hold a pencil.

“His determination drove him on,” Rita says. “If there was any chance that he could do something he gave it everything he had.”

Hedderman says the three main drivers on his road to recovery were: “1. Luck. 2. Support. 3. Self-confidence and resilience.” He was lucky that he had the opportunity to regain movement when many spinal injury victims don’t, no matter how much determination is in their hearts. His wife led a great support network and his battles with adversity playing sport and in his military training made him attack every opportunity.

The halo brace came off in March 2015 and on April 10, with many tears and thank yous, he was discharged from hospital. He immediately enrolled in a treatment program at the Enoggera base, undergoing hydrotherapy and walking exercises on an “anti- gravity” treadmill.

He was back at work the next month, though his hands had little grip or sensation. He tried running but could shuffle no more than 50m.

Still it was a start. “Fifty metres quickly became 200 and within two weeks I could run a kilometre,” he says.

He cried after completing 2.4km in just over 12 minutes in July 2015. Six months after being declared a quadriplegic, he completed a 10km race at Woody Point in under an hour.

During his rehabilitation, an occupational therapist recommended Hedderman use a keyboard to write to exercise his hands and fingers. He began slowly tapping out some lines from the autobiography of the Irish rugby player Brian O’Driscoll but then decided his own story was more interesting.

Day after day, ever so slowly, Hedderman pressed down on his keypad, trying to make his brain and fingers work in unison. Weeks went by as he poured out the story of his accident and his fight to recover in a cathartic psychological release that also made his fingers ever more nimble. Before long he had the genesis of an inspiring biography called Unbowed, now published in Ireland and Australia.

In it, Hedderman details his experience in building and using the sort of resilience never more vital than in this age of coronavirus. His book is also a homage to Rita, 37, who teaches French at Moreton Bay College and was always there for him in his many hours of need.

“She was all-in no matter what,” he says. “My self-belief, my recovery and my life are due to Rita enabling me. I love her dearly and my respect for her knows no bounds.”

Hedderman says it was because of Rita that he was able to go skydiving again a year after being paralysed and that in 2017, despite some lingering co-ordination issues, he could complete the army’s Physical Employment Standards Assessment, a torture test that, among many arduous physical challenges, includes a 15km hike carrying a 45kg pack.

The couple’s greatest triumphs though are Lara and Isabel, whose presence has convinced Hedderman to leave the military after almost two decades for a quiet suburban life and an office job in risk management with Ernst and Young.

“From where I was on that first day in hospital to where we are now, we have to pinch ourselves that we are so lucky,” Hedderman says.

“Lying in that hospital bed, all my functions were gone and we didn’t know what would come back, if anything.

“Now Rita and I have two lovely daughters and this beautiful life in Queensland.”

Old habits die hard and each morning Hedderman still gets out of bed at dawn to push his body through a gruelling exercise regimen in his home gym.

But the former Special Forces officer recently sold his skydiving rig to buy a Ford Mondeo.

“I guess that’s what you call a real dad thing to do,” he says.

Unbowed by Billy Hedderman, Big Sky Publishing, $35

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

I polled my lady friends – we all agree this gives us the ick

Women are now being allowed to do this – the only problem is they don’t want to be anywhere near it.

Only now does my lifelong stalker finally have a name

Since Kelli Armstrong was a little girl, she has been stalked by a mysterious shadow attacking her mind and spirit. At last, 40 years on, she has a diagnosis. WARNING: DISTRESSING CONTENT