From child soldier to single dad: The power of love has healed me

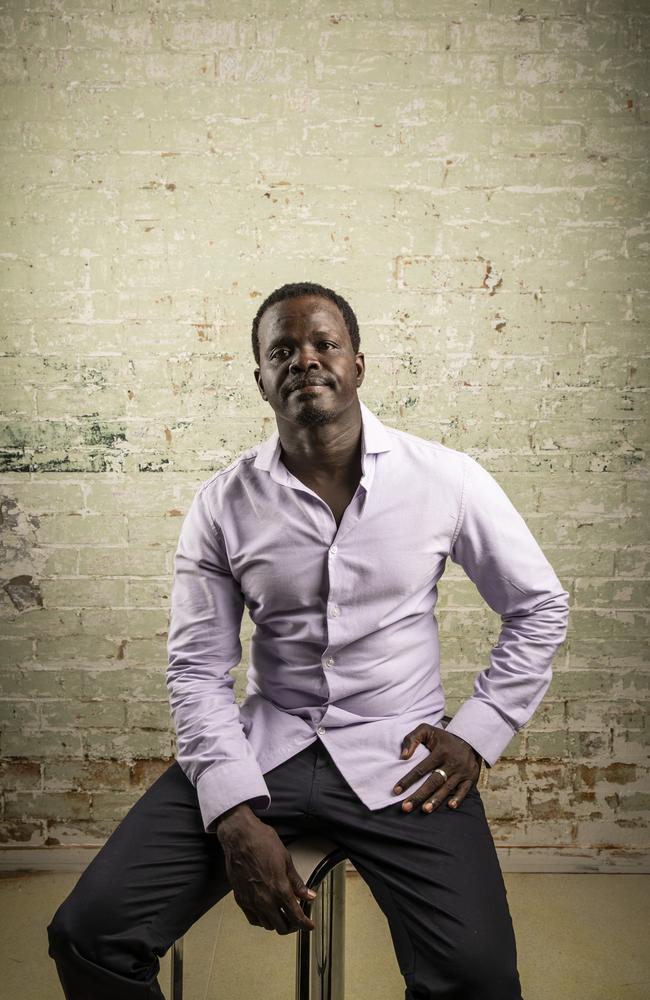

Former South Sudanese child soldier Ayik Chut is an author and actor. Read his remarkable story experiencing war and torture before finding a new life as a single dad in Queensland.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN THE moments before he wakes, Ayik Chut hears the hum of swarming blowflies. He sees dried blood caked on his skin that is crawling with flies and maggots; he smells the decay of his own dead body.

He looks up from his grave in the African sand and watches vultures spiralling down to feast upon him. This time, he really must be dead.

With all his willpower, he hauls his eyelids open. He sees that he is safe in his bed in Toowoomba, the Garden City, in southern Queensland’s Darling Downs, a world away from the horrors in his mind.

- South Sudan refugee encourages youths to learn from his story

- Young gun in South Sudan and A-League sides’ sights

- From child soldier to South Aussie law graduate

He gets up, eats breakfast and goes to school.

NEW LIFE

Now aged 43, Chut lives in Indooroopilly, in Brisbane’s west. He has a new life as a single dad to his 16-month-old daughter, who he has been sole carer of since she was eight days old. He also has a son, 13.

He no longer suffers the horrifying, recurring nightmares that chased him in his youth. But he certainly still remembers them.

Chut was a child soldier in the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army, signing up to fight for his country’s independence, AK-47 in hand, at age 12. He witnessed years of atrocities and was himself brutally tortured – hog tied and whipped, with chilli powder rubbed into his torn skin.

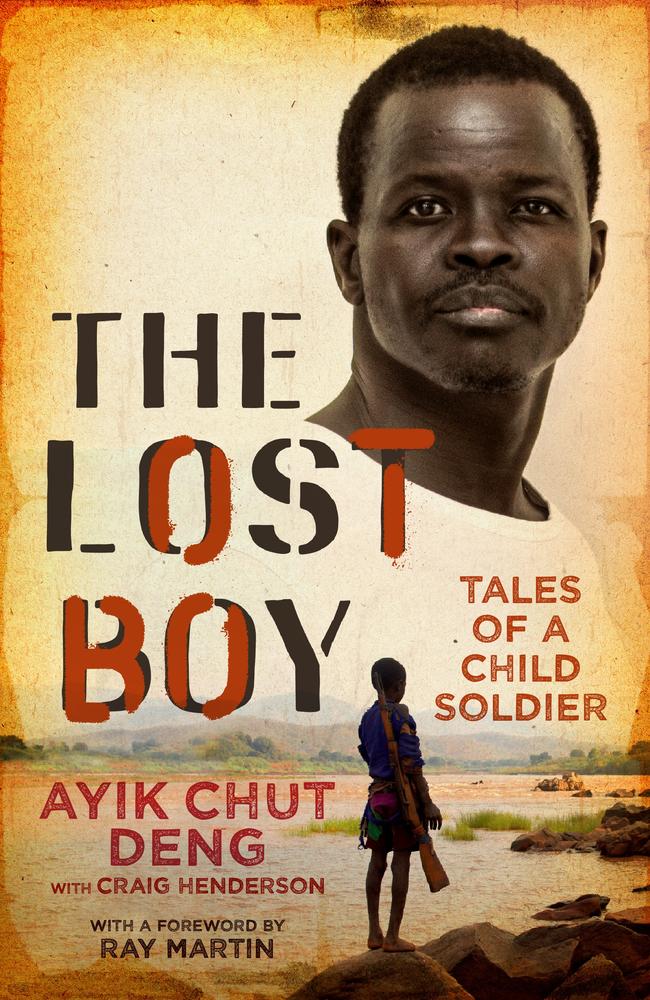

He has written a book (published under his full family name of Ayik Chut Deng) about his experiences, The Lost Boy: Tales of a Child Soldier, in which he describes the torture as hours upon hours of “total, endless, blinding pain”.

Arriving as a refugee in Australia in 1996, aged 19, with almost no formal education or English, Chut was resettled in Toowoomba where, as a “six foot two adult black man” he began grade 10 at Centenary Heights State High.

It is not the African way, he says, to speak of bad dreams or memories or any hauntings of the past. To do so would be a sign of weakness.

And so, for many years, Chut never spoke about his experiences of the war. He never told a soul about his nightmares, not even his siblings who had also settled with him in Toowoomba.

He just wanted to fit in to his new Australian community.

Finally, in 2002, he was referred to a psychiatrist but was misdiagnosed and medicated for schizophrenia. It would take eight years of incorrect and “mind numbing” medication before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – now recognised as a genuine war disability – was correctly diagnosed.

Those eight years would take their toll on Chut. In this time, he lost sight of his dreams to become an actor (he had previously appeared in some local television ads, as an extra in television series Cybergirl and movies Scooby Doo and Curse of the Talisman) and instead became a “drugged out, volatile, risk-taking, emotional basket case”.

He developed a dependence on marijuana and alcohol, mixed illegal drugs with his prescription, hung out with the wrong crowd and became a drug dealer, a reckless repeat drink driver, he faced criminal charges of assault, obstructing police and disorderly conduct.

He would finally go to prison in Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre. He seemed lost to the world.

But in the most unlikely of comebacks, Chut has how written a new chapter for his life.

After all his childhood trauma, his mental health misdiagnosis, his drug taking, criminal offending and his sense of failure about not making the most of his new Australian life, Chut drew a line in the sand.

In 2008, he quit marijuana and in 2010, he went “cold turkey” off Seroquel, the drug he had been prescribed for schizophrenia. Finally, in 2013, he gave up alcohol. It took him five years, but he says he dragged himself out of the “deep hole I had dug”.

Today, he is “100 per cent drug free”. “I won’t even take Panadol,” he says.

Chut has since found more acting work as an extra in films such as Thor: Ragnarok, Aquaman, San Andreas, Dora and the Lost City of Gold, Don’t Tell and the television series Wanted and a speaking role in Safe Harbour.

He has a new part in the next series ofTV drama Harrow and in the upcoming (as yet untitled) Elvis film directed by Baz Luhrmann.

But aside from his burgeoning acting career, there is another, much more compelling reason to stand up and be a good man – his children.

Being a single dad to his baby girl, Achol Sunday, is never a role he ever imagined, or, if he’s honest, even wanted.

As any parent will readily attest, raising a child is not easy.

Chut, with zero knowledge or experience of how to raise a child, let alone a newborn baby, admits he was at first hesitant to take on sole responsibility for Achol Sunday, who was born while he was working on his book.

After one month of caring for her, he even took her to his local church to surrender her to a female parishioner. He just wanted to sleep.

But after a good rest, he collected her again and now couldn’t imagine life without her.

“In the early months when Sunday was given to me I used to asked myself, ‘Why do I have to suffer in life like this?’,” Chut says.

“I felt I have suffered in the war as a boy soldier, I came to Australia and was misdiagnosed for eight years, I went to prison and now I have this little human in my care without any knowledge of how to raise her.

“I felt like I was just meant to suffer for the rest of my life. But when I look back now, having my baby is the best suffering I have had in life.

“Now she’s everything to me. Caring for my daughter has changed me and made me more responsible. She is healthy and happy and she loves to give everyone a hug.

“She makes me laugh, she makes me cry. She even talks to me in a language I can’t explain.

“She’s my number one friend … now I miss her when she’s at daycare.

“I never thought my life would end up this way – a child soldier raising his own child, but it’s a happy ending.

“Australia has given me my own life and two of its own – my children.’’

THE HORRORS OF WAR IN SOUTH SUDAN

The Republic of South Sudan, a landlocked central east African nation, is the world’s youngest country, winning its independence from the Republic of Sudan (North Sudan) on July 9, 2011.

The former Sudan was roughly divided into two main ethnic groups – Arab Muslims in the north and those with tribal African cultural traditions and Christian beliefs in the south (though there are hundreds of ethnic and tribal divisions within this) – and has long been ravaged by civil war. Even since the south’s succession, the country still faces serious civil unrest.

Sudan’s first civil war was fought from 1956 to 1972.

Then the 22-year Second Sudanese Civil War raged from 1983 to 2005, claiming an estimated two million people, many who died from mass killings as well as starvation and drought. Another four million South Sudanese were displaced.

Census figures show Sudanese arrivals to Australia peaked between 2002 and 2007 and the 2016 Census recorded almost 7700 South Sudan-born people in Australia. (Figures may be skewed, however, as the South Sudan-born were previously included in the Census count under Sudan-born. They were first counted separately in the 2011 Census).

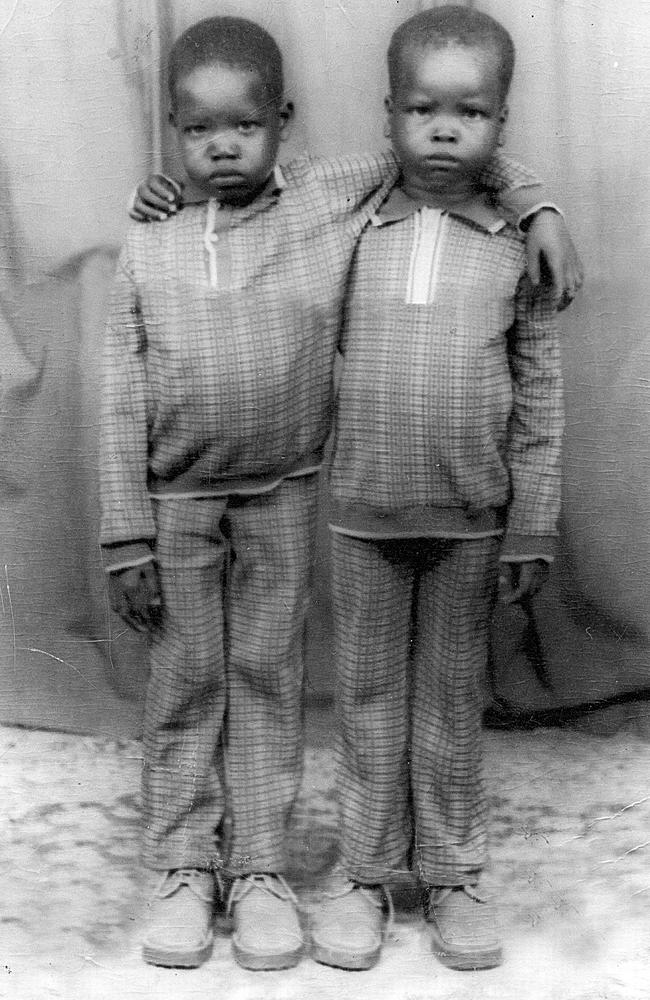

Chut was born a tribal Dinka boy, the middle child of seven siblings and part of the largest ethnic group in southern Sudan. The Dinka, Chut writes in his book, are known as the tallest humans in Africa and “owners of the blackest skin”.

Traditionally, the Dinka live in a commodity-free society where “a herd of cattle is the Dinka’s truest measure of wealth”.

Chut writes they live “modest, uncomplicated and gentle lives in perfect harmony with nature”.

“For many centuries we have raised cattle, farmed crops and sung our songs in simple grass-hut villages along the fertile plains and swamplands that flank the White Nile,’’ he writes.

But this was not to be Chut’s path.

His father, Chut Deng Achouth, died in 1983 when Chut was six years old in a suspected, but unconfirmed, case of poisoning.

It was also the year civil war broke out.

Then his beloved older sibling, his brother Aleer, was shot and killed in the early years of the war, meaninglessly, after a small dispute with a fellow soldier.

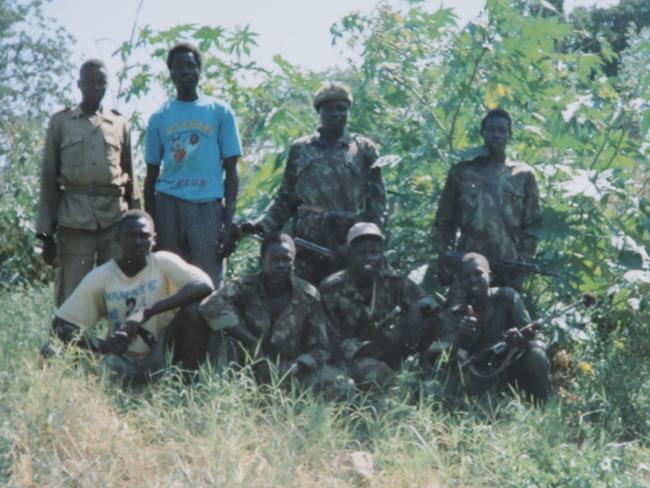

At age 12, Chut was one of tens of thousands of Sudanese boys in the ranks of theSPLA’s Red Army, “a rag-tag force of killer kids” primed to lay down their lives in the fight for an independent South Sudan.

He was also determined to avenge his brother’s death.

But not long after joining the Red Army, the relentless training drills from 4am to midday, perpetual thirst and hunger, whippings by trainers, the heat and the terror of being mauled by hyenas as they slept on the dirt in tents, left him mentally exhausted.

He ran away but was recaptured and the consequences were severe. His torture began at the hands of a 16-year-old boy called Anyang Reng, who ran the child soldiers’ prison (and who also happened to be a relative of the youth who had killed his brother).

As punishment, Chut would be bound tightly at his elbows, wrists and ankles, then flogged until he passed out. For hours on end, he was made to complete a series of gruelling disciplines – standing on one leg, jumping squats and rolling on the ground until his wet shirt was dry. Then there was the chilli powder rubbed into his raw wounds. It was merciless “pain on top of unbearable pain”.

He remembers one child who was tied up tightly at his elbows for several days and then had to have both arms amputated because they had lost blood-flow.

Chut ran away several more times and each time he was recaptured. Each time, the punishment seemed worse than the last.

He consequently spent years planning how he would torture and kill Reng. He wanted his to be the last face Reng saw before he died.

But he never had the chance. As the war progressed, they went their separate ways and then Chut moved to Australia. He assumed Reng had died in the war.

Then in 2005, while attending a wedding at Mary Immaculate Church in suburban Annerley, in Brisbane’s south, the incredible happened.

At the end of the service, from across the room, Chut thought he could see Reng, the tormentor of his youth. He thought his mind was playing tricks.

In this Brisbane church.

In shock, Chut walked out without making any contact. He went straight home, his mind racing.

“Is this right? You pinch yourself. Maybe it was God playing with my mind. It can’t be true, but it is,” Chut says.

“Then the flashback came. How he was torturing me and the other child soldiers. I was saying, ‘He needs to die’. I grabbed my keys to return to the church but I realised the service had finished and he wouldn’t be there anymore.”

A few years passed before Chut again crossed paths with Reng, who lives in Logan, south of Brisbane. This time it was at a party at a friend’s house. Chut, who was “a happy drunk” at the time, spoke briefly to him. “I walked up to him and said, ‘Do you remember me? Do you

remember everything you did to me in the war?’

“I said to him, ‘You are lucky. Australia saved me and it has saved your life too. I wanted to kill you when we were in Africa … I didn’t want to use a gun, I wanted to use my bare hands, to torture you slowly until you died’.

“If he said something wrong, I was ready to explode.”

EXTRAORDINARY MEETING

Then in 2017, Chut, now living a clean and sober life, found an interesting casting call on website Star Now, which matches producers and casting directors with actors. It was for an SBS television program called Look Me in the Eye, seeking two estranged people to sit in a room and look into each other’s eyes, with no words, for five minutes. Chut offered his story of a boy soldier and his torturer.

Chut and Reng featured on the program, hosted by veteran journalist Ray Martin, in 2017.

“I’d been angry all my life,” Chut says.

“But I forgave Anyang. Everybody needs a second chance. And it helped me. I just want to live the rest of my life happy.

“Now, I don’t want to kill anything, even an ant in my home. In Africa, I used to shoot birds for the sake of it and I killed monkeys to feed a leopard that was a pet of our commando unit.”

(This particular leopard went on to almost maul a young soldier to death but he was saved by Chut. The rescued soldier, Bul Aguang, now lives in Sydney).

Incredibly, Chut took his forgiveness of Reng a step further and introduced his young son to him. Chut even stayed for one week in Anyang’s Logan unit and they still keep in touch “every now and again”.

From never talking about his traumatic childhood experiences, Chut has come full circle with his book, authored with the help of NSW south coast-based journalist Craig Henderson.

“As soon as I started talking about it, I started feeling like I was getting better. This book is the good, the bad and a bit of funny. It’s from my heart and everything I went through,” Chut says.

“I know a lot of child soldiers who live in Brisbane now and a lot of them turn to alcohol because they are traumatised. We don’t talk about it in our culture.

“At first, I just wanted to fit in to the Australian community and not talk about my life.

“I didn’t think talking about it would help but it gave me some ways to deal with the problems I was having.

“And maybe me talking about it will help one or two others. The trauma will always be there but it has reduced the problem into half.”

Incredibly, Chut says his book will be the first time his family will learn about his nightmares and difficulties.

His mother Achol Aguin Majok (who Achol Sunday is named for) lives in Toowoomba. The city is also home to his older sister Aguil and younger brothers Deng and Garang.

He also has a sister Akeer who lives in Canberra and a sister, Yar, who remains in South Sudan.

“When I was my son’s age, I was carrying an AK-47. It breaks my heart to think of what I was doing at his age,” Chut says.

“I missed out on my childhood. But when I play with him, I feel like a child again, like I’m catching up.

“And now I look back, there’s so much to live for. I’ve lived the worst life on the planet and the best life now. Where I live now, to some countries and tribes in Africa, only a king could live like that.

“I have a nice unit, I have a fridge, a microwave, food in the cupboard.

I have told my son that the food that one person eats every day here – breakfast, lunch, dinner – five or sixor more children inanother part of the world eat in a day and be happy.

“I used to scavenge in bins for food when I was four or five. I’d run from home straight to the dump. There are people starving in the world every day. But, in Australia, there’s so much and there’s help if you need it.

“I still pinch myself that I have this life.”

Chut is no longer chased by nightmares. His dreams are now of a different reality.

He dreams of more acting work. He is also working towards becoming a police liaison officer with troubled youth. He volunteers, when needed, with the Police Citizens Youth Club in Fortitude Valley.

He wants to be a good father and is still learning every day. He dreams (when he gets enough sleep) of giving his kids a happy childhood.

The Lost Boy: Tales of a Child Soldier, Vintage Australia, $35, out Tuesday