Ex-undercover cop shares dark and damaging side of the job

He was a police officer in the state’s most corrupt era, now Keith Banks reveals the dark and damaging side of the job that made him almost take his own life.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOR the glory, there has been a price to pay.

The bloody crime scenes, witnessing the point blank shooting murder of his friend and colleague, the long half-minute negotiating with a man holding a de-pinned grenade.

For years, the memories relentlessly flickered into his mind.

How home DNA kits are delivering shocking results

Meet Joanne Connor who has watched the movie Bohemian Rhapsody 108 times

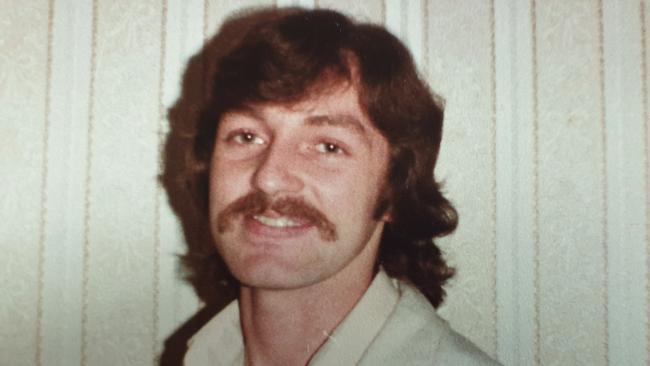

Former Queensland undercover police officer Keith Banks is one of the state’s most decorated officers. Serving for 20 years from 1975 to 1995, he cut his teeth in the most corrupt era of Queensland’s police history and was front and centre of some of the state’s most high-profile crimes.

His time in the Queensland Police Force (later Queensland Police Service) saw the Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct – known as the Fitzgerald Inquiry (1987-89) – that dealt the death knell to the 19-year Bjelke-Petersen premiership, sent three former ministers and police commissioner Terry Lewis to jail and forever changed the face of policing and the state’s political landscape.

Banks, 62, says he is proud to have emerged from the Fitzgerald Inquiry with his reputation intact and a promotion in 1990 to detective sergeant in the Bureau of Criminal Intelligence.

He has twice been awarded the police force’s highest honour, the Valour Award. He has also received The Bravery Medal from the Australian Government.

Early in his career, he served as a full-time undercover cop and later in tactical response teams, the bomb squad and the Bureau of Criminal Intelligence, rising to the rank of detective sergeant.

He has some stories to tell.

Banks, drawn to the “sharp end of policing” and looking for adventure, volunteered for undercover work when he was just 21 years old.

It was an era when undercovers, who spent their time living and dealing with “crooks, prostitutes, drug dealers and bikies”, routinely smoked cannabis, a situation Banks says was informally condoned.

“I started undercover never having drunk any alcohol,” he says.

“My first drink was atthe Inala Hotel. I met the informant, this big guy, and he ordered two beers. I said, ‘I don’t drink’, and he said, ‘You f---ing do now’.

“Two months in the job and I’m doing two lines of speed at gunpoint in a filthy place in Auchenflower.

“And I smoked a lot of pot in those days.

“Unlike the movies, we weren’t followed, we didn’t have surveillance looking after us, we were just by ourselves.”

It was also an era before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was understood or even recognised and Banks spent years suffering its effects – short-term anger, impatience, anxiety, sleep problems, emotional numbness, suicidal ideation, self medicating with alcohol, guilt and remorse.

In one chilling moment, he put the cold barrel of his police issue 9mm pistol in his mouth.

He says his experience of undercover work changed him “irrevocably” and he has written a book, with Adelaide’s Flinders University creative writing tutor Ben Smith, about his experience, titled Drugs, Guns & Lies: My Life as an Undercover Cop.

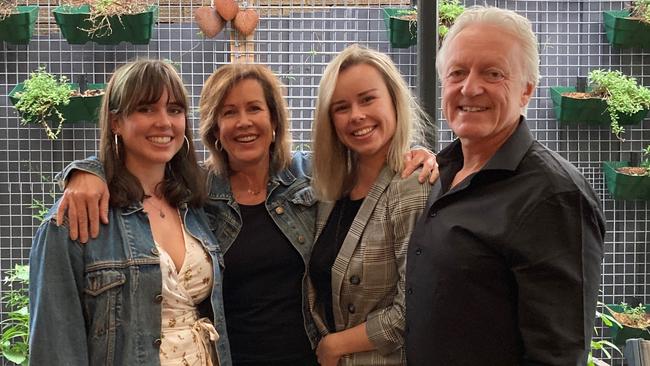

Banks is now based in Melbourne as the chief operations officer for the Real Estate Institute of Victoria, a world away from policing (though he “still bleeds blue”).

He says his story is not a happy one but one that needs to be told.

Banks began writing his story in 2013, as an explanation of sorts to his daughters, Karly and Julia, to help them understand the moods and emotional distancing he now knows to be symptoms of PTSD. Banks was only formally diagnosed with the condition in May 2019. His wife of 25 years, Jennifer, 57, is a former Victorian police drug squad detective. Banks knows it hasn’t always been easy living with him and says he is “a very lucky man”.

The memories of his police days are still vivid in his mind but he also had a wealth of detailed information to draw from, thanks to 20 or more Spirax notebooks he kept while undercover, written at a time when listening devices were too big to be concealed under clothing.

He kept the notebooks at his home and realised they were a treasure trove of details from those years of policing.

“The more I wrote, the more of a catharsis it became and it just started to flow,” he says.

“Part of getting the book published for me is to start a genuine and authentic conversation about PTSD and police and also first responders. The suicide rates among cops is epidemic, it’s just horrible.”

He also wanted to tell the story of Harry Shehab – a “smart, idealistic and honest” police officer who began using heroin while working deep undercover targeting drug rings. Banks writes that Shehab became an addict and “the only uniformed police officer in Queensland with a heroin addiction”. In 1992, Shehab was paid out his job as medically unfit with “no therapy, no rehabilitation, no responsibility”.

Banks says Shehab, who put any police payout “up his arm”, went on to commit armed bank robberies in Adelaide and Brisbane and served a total of 10 years in two prison stints.

“Harry joined as a fresh faced young idealistic man, as we all did, to volunteer for undercover and within 12 months was using heroin,” Banks says. “I have been wanting to tell Harry’s story for a long time because what happened to him was a direct result of his undercover work.

“I haven’t named them but there were certainly two detectives who were providing him with heroin because Harry was a valuable asset for them to use to further their own arrest records.

“That’s been burning at me for years. Harry got it the worst but none of us came out unscathed.”

Banks says Shehab has now “completely turned his life around” and is retired in Queensland.

There have been hundreds of appalling,

mind-searing scenes. Compounding and building, Banks says, like sediment on a riverbank.

It was an accumulation of “dead bodies, car smashes, rape victims, the sound of people dying and the sound of people trying not to die”.

“We’d kicked in doors, been shot at, infiltrated heroin importation rings and mafia circles,” he writes.

“We could buy drugs, fool dealers, and we could drink enough to wash it all away. So that’s what we did.”

Banks reveals a suicide he attended in Red Hill in Brisbane in 1983 “still stays with me … I can still remember that sight’’.

He writes: “The entire back half of the man’s head had been missing … his face was still intact, vacant and wide-eyed, but the wall behind him was painted with a spray of blood and brain matter. I remember being overwhelmed by the sheer breadth of the splatter. It seemed to cover the entire wall, it seemed impossible that so much could be contained within a person. Instinctively, out of self-preservation, I mentally grabbed hold of myself. It’s not a human being, It’s just a piece of meat.”

One of his most horrific days of his police career was witnessing the shooting murder of his colleague Senior Constable Peter Kidd at Virginia, in north Brisbane, in July 1987. They were part of a tactical response group for Operation Flashdance to arrest Queensland’s most wanted criminal Paul James Mullin, a violent armed robber and escapee from Long Bay Gaol.

Kidd was shot five times at point blank range with a high-powered rifle and later died in hospital. Another constable was injured and Banks and another officer returned fire and shot the offender dead.

Later that morning, Banks was interviewed by the homicide squad for several hours.

“Then they took us upstairs to the Police Club at the old CIB headquarters in Makerston St, bought us beers, got us hammered and drove us home,” Banks says. “I went to work the next day and rolled up for debriefings and straight back on to tactical work. There was no psychological support. In hindsight, it’s quite heartbreaking. A lot of people suffered but we just didn’t know.”

About two months later, in September 1987, Banks reached “a dark place of despair”.

Alone at home, he came within a whisker of suicide. He had authority to have his police-issue pistol with him because, after shooting Mullin dead in July, he and his colleague had “a credible death threat’’ from the criminal gang in Sydney associated with Mullin.

“I was in such a dark place of despair I actually put my firearm in my mouth and thought about ending it all,” Banks says. “I was sitting at home and the only thing that stopped me, in a moment of clarity, was remembering how bad that suicide I had attended [in 1983] was. It wasn’t through self preservation, it was more if I squeeze the trigger, then the woman I was living with will come home and see all of my brain splatter and blood and all that horrible stuff.

“In that moment of clarity, I took the weapon out of my mouth and put it down. That was a really dark place.”

Banks also attended a confronting bloody domestic violence scene at Wynnum West in June 1989 resulting in the murder of young Constable Brett Handran, a two-year-old girl and the suicide of the offender. Four other people were seriously wounded.

Banks says he “flashed straight back” to the suicide scene from 1983. “It was the same rifle, the same damage to the skull,” he says.

“But because it was after Peter [Kidd] was murdered I was just so emotionally cold. It was more contempt that I felt.”

In September 1993, Banks responded to a “shots fired” call in George St in Brisbane’s CBD. He ended up negotiating a siege situation with a man sitting in the foyer of the MLC Building who was armed with 16 sticks of gelignite, three electronic detonators, a rifle and hand grenade. “I spent an hour-and-a-half negotiating with this guy who was a Vietnam veteran,” Banks says.

“At one point when I thought I had talked him into surrendering the rifle, he produced a hand grenade and pulled the pin.

“With a grenade, when you pull the pin out, there’s a lever and if you keep your hand wrapped around the lever it’s all good. As soon as you let the lever go, you’ve got about 5-7 seconds before it detonates.

“When he pulled the pin out, I said to him, ‘I’m not going anywhere mate. I’ve got enough f---ing nightmares as it is and I’m not going to let you be another one’. I can remember it vividly. And we connected on that level.

“The pin was out for about 30 seconds, maybe longer, and that felt like a long time.

“Thankfully he put the pin back in. If that thing had detonated … even if I’d been able to get up and run for the entrance, a sympathetic detonation would have set off the 16 sticks of gelignite and there’s no way I would have got out in time.”

In hindsight, Banks says at the time of the siege he was well down the path of PTSD and was “addicted to taking risk”. “Part of the condition is that you become addicted to adrenaline and risk and I was pushing the envelope. I was really facing the rush I guess,” he says. “These days, I’m certainly in a much better place but I don’t think you ever fully recover.”

Before he was old enough to talk, Banks moved with his mother from Sydney to Tambo, a central Queensland town halfway between Brisbane and Mount Isa. His parents had divorced and there was “no assistance for a mother whose husband had left”.

For the first six years of his life, he was happy, living with his mother and grandparents in the farming town.

It could have been a different life, a different path. As Banks writes: “If nothing had changed, I might be living in Brisbane now, working as a lawyer or in social services. I would go to work in the morning, come home at night, and I never would have killed anyone.”

But things did change for Banks when his mother met his future stepfather and the three of them left Tambo, living in a caravan on the road, moving to wherever there was work.

They married when Banks was six years old. It was also the first day his stepfather hit him.

Banks says his late stepfather proved to be a violent alcoholic and the rest of his childhood was marred by domestic violence and constant moving. In the first two years, he went to 12 different schools. But wherever they went, Banks says the inside of the caravan was “the same tightly wound spring that could snap loose at any moment”.

“We carried our family life with us, an enclosed world where I was too scared to speak, where my mother was too scared to stick up for me, and where there was nowhere to hide,” he writes.

Perpetually the new kid, small and shy, he was also tormented by schoolyard bullies.

He spent a two-year reprieve back in Tambo with his grandparents before moving again with his mother and stepfather to Mount Isa, Cairns and Charters Towers.

Banks says he joined the Police Force to stop those who hurt others. He wanted to fight crime but instead found himself in a world that endorsed it. Facing police corruption, he says, was “almost soul destroying”.

“I naively thought everyone was like me and wanted to fight the bad guys and protect good people,” he says.

“The vast majority of men and women in the organisation were honest and hardworking but it was a small cohort of influential cops who were bent who spat on the badge. You found your own level, you associated with people that shared your values and didn’t associate with those who didn’t. It was that black and white.”

Banks left the QPS in February 1995 and he has been based in Melbourne since 1996.

For the past three years he has been REIV’s COO, following his position as deputy executive director (Victoria) in the Housing Industry Association. He has also worked extensively in senior security and risk management.

Drugs, Guns & Lies is his first book and it has been released as the first of two parts. A planned (already written) second book will cover the second decade of his police career.

“Undercover certainly took a toll on us more than normal policing and I wanted to write about the impact it had on young idealistic men [there were no women undercover then],” he says.

“This is a story about the impact of that job on people. My hope is that this book may go a little way to helping readers look at police officers and the work they do through a different lens. They don’t just write traffic tickets.” ■

Drugs, Guns & Lies: My Life as an Undercover Cop by Keith Banks,

with Ben Smith, Allen & Unwin, $30