‘Delta plus’: Supercharged new UQ vaccine to fight deadly Covid strains

Australia was left devastated when the University of Queensland was forced to scrap its Covid-19 vaccine. But now it’s poised to push ahead with an exciting new ‘Wave 2’ version.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was like something out of an action movie: a small Esky filled with scientific material must make it out of Australia and into the hands of Dutch scientists to get the answers that could save the world.

But the world is in turmoil, flights are being cancelled and the Esky keeps getting bumped off. For two weeks, the precious cargo hasn’t budged from the laboratory of the University of Queensland.

It’s crunch time.

On one crazy Saturday in March last year, in the midst of the first and frightening Covid-19 lockdown, nothing was more important for some of the brightest scientific minds in the country than to get that Esky on a plane. They hit the phones.

Like any blockbuster, this plot is filled with twists and turns, failures and triumph, and it’s far from over.

It’s the story of the UQ Covid-19 molecular clamp vaccine, the one that hit a massive hurdle in December last year but is back on track to offer hope for a new vaccine to add to the arsenal helping the world fight the deadly disease.

Back in March last year, as the pandemic took hold, there were no vaccines for Covid-19.

No one knew when, or if, an effective vaccine could be developed but the UQ team was in the race – if only they could get the Esky and its contents to The Netherlands.

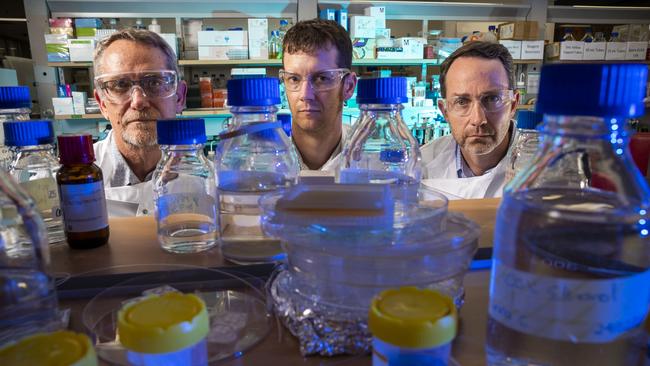

“It was basically going to tell us, ‘Does our vaccine work?’,” says Professor Trent Munro, the project manager of the UQ vaccine. “We were thinking, ‘We must know someone who can help get it on a plane’.”

Maybe they could send a PhD student on a $30,000 first class ticket to nurse the Esky. Quarantine requirements scotched that. Perhaps a private jet?

In the end, it came down to contacts – and a willingness to back this great Australian hope. Munro and virologist Professor Paul Young, the project’s co-lead and head of UQ’s school of chemistry and molecular biosciences, called the university’s then Vice-Chancellor, Peter Hoj.

Hoj contacted the boss of Qantas, Alan Joyce. Joyce gave them the name of his go-to man for global logistics.

“And he was straight on to it, and he’s saying, ‘Here’s the group we’re going to work with, here’s how we’re going to do it’,” Munro says.

“It was a bit bumpy,” he recalls. “We missed two flights, it got stuck in Hong Kong, then it went somewhere in Europe.”

Once the Esky landed at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, scientists from the Dutch lab picked it up and whisked it away to have the material inside tested on hamsters, which are not used in Australia. Those results were good.

“There were so many moments like that,” Munro says. “So many times when we thought, ‘This is it, we’re done, just give up now, this is not going to happen.’ And every time the huge barrier came up, we found a way through. Every time we were waiting for a technical bit of data that we thought was make or break, it went our way. Every single time.”

Until it didn’t.

“All that build-up to that final decision not to proceed into the key human efficacy studies, made it all the worse. Given the mountains we’d climbed.”

When it all came crashing down last year, the pain for the scientists who had been working 24/7 on the vaccine was palpable.

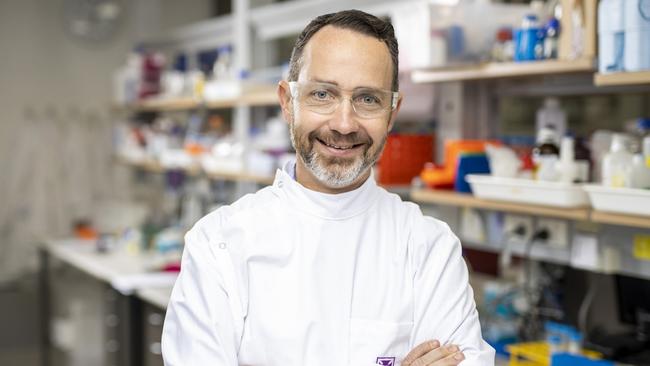

Young had to front the media the next day to let the public know Queensland was out of the race. He’d felt ill all night. “But I said, ‘We’ll turn around and pick ourselves up from this and progress with an alternative Clamp 2.0’,” Young recalls. “And that’s what we’ve done.”

THE SETBACK

With all the problems of the Pfizer rollout andAstraZeneca hesitancy, it’s easy to lose track of how fortunate we are to have vaccines for Covid-19.

Right now, according to the World Health Organisation’s vaccine tracker, there are close to 300 vaccines still in preclinical or clinical development. Only about a dozen have been rolled out internationally.

The pandemic supercharged the vaccine development efforts of Big Pharma, governments and academia in a way never experienced before.

Scientists weren’t starting from scratch; coronaviruses have been studied for decades, with much understanding about spike proteins already garnered.

But as Covid-19 menaced the globe, scientists began sharing often jealously guarded data, myriad projects were shelved to focus on the virus and hard-to-get funding for development and trials was splashed about to find an answer.

In Brisbane, the UQ team had been plugging away on its vaccine technology for almost a decade when Covid-19 hit. For a number of years, the work was unfunded.

And if the virus had held off for just one more year, the issue that killed off the first clamp vaccine would have been discovered.

To be clear, the revised Clamp 2.0 does not use fragments of the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. Not a skerrick of it.

It was these pesky hints of HIV showing up as false positives in some HIV diagnostic tests that ended UQ’s first vaccine.

Not poor results from the first phase of clinical testing, not bad reactions, not anything that suggested the vaccine was unsafe. In fact, the clinical data the team got in from its initial human testing was “awesome”.

But explaining that to an already nervous populace was a communications challenge that, in the end, no-one involved was prepared to take on. At least, not when Pfizer and AstraZeneca had vaccines that were looking promising.

Says Young: “If that hadn’t been the case, we probably would have gone forward.”

Beyond the communications battle and the risk it raised of vaccine hesitancy was the flow-on effect the false positives would have on HIV testing worldwide. Some tests are more precise than others.

“In the developing world, they tend to have the cheaper ones which are much more likely to have picked this up,” Young says. Unless tests globally were upgraded, these cheaper tests raised the unpalatable prospect of millions of people falsely believing they had HIV.

So, given there was a chance that false positives for HIV could be picked up, why did UQ use it? That answer starts in 2011, when the brains behind the molecular clamp technology, Associate Professor Keith Chappell, returned to UQ after doing postdoctoral research in Spain.

Chappell wanted to explore his idea for a molecular clamp in protein, or subunit vaccines, after being involved in a seminal study on how proteins in viruses transform, like molecular shapeshifters, when they enter a cell. This can reduce the effective targeting of the virus with a vaccine.

In protein vaccines, a genetically manufactured part of the pathogen being vaccinated against is injected to prime the immune system and prompt an immune response if the body ever comes in contact with the real thing.

The now highly recognisable coronavirus spike protein is the one used in vaccines to target SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. But it also transforms. Fragments of the spike protein of HIV, gp41, were added to the genetically sequenced SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to hold the molecular infrastructure in the correct state to create a stable and effective vaccine.

The team tried a few options other than HIV, but it worked best. But Young emphasises that it was not an exhaustive search because this was proof of principle research. A journey of discovery.

Over the next few years, the clamp was used in animal models on about 10 different virus families and it worked for all of them. There was no indication of HIV because tests only detect human antibodies. Human clinical trials were a long way off.

Come 2017, the Norway-based Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was formed, with funding to help develop vaccines for a pandemic.

It chose the UQ team’s work on the clamp as worthy of funding, granting it $15m for three years from 2019. The beauty of this platform technology would be that when an unknown virus came along, the molecular clamp could be used.

The team made a plan. They’d do human clinical trials on a clamp-enabled vaccine for influenza in 2020, and the same for the coronavirus known as MERS, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, this year. The HIV false positives would have shown up in the flu trial. The team would have made changes.

But SARS-Cov-2 got here first.

The UQ team responded. From the moment Covid-19’s genetic sequence was released on January 11 last year, Associate Professor Dan Watterson was designing the first vaccine construct.

On January 21, CEPI asked UQ to prepare a trial and commit to taking a vaccine to manufacture. So began 10 months of intense work to produce a Covid-19 vaccine.

“It was exciting and frightening,” Young says. “We were pretty confident of it, the data we had already generated in animal studies had been very promising. But being an academic organisation, it was a challenge to commit because we’re not a vaccine manufacturer and we didn’t have anyone lined up to collaborate with at that time.”

CSL filled that breach. It took the risk of producing the vaccine ahead of extensive clinical trials.

The normal chain of events is that production follows successful final phase, or Phase 3, trials. But the world was experiencing something far from normal. The trials could not be rushed but the pre-production of the vaccine would mean a rapid release once safety and efficacy were confirmed.

The public was on side, too. Young says that after its call out for those aged over 55 to participate in the Phase 1 trials, more than 7000 people made contact. Only about 100 were needed. Each of them had to sign a consent form acknowledging there was the potential of false HIV diagnosis. No-one baulked.

The results of the Phase 1 trials were excellent. Beyond expectations. There was growing optimism that Australia would have a homegrown vaccine to fight the deadly disease.

But those results did not test for HIV. In the rigorous world of science, permission to test for HIV had to be approved by an ethics committee.

Meanwhile, Munro was busy sourcing as many HIV tests as he could. “I was ringing sexual health clinics to say, ‘Hey, what tests do you guys use, what’s the algorithms?’ I think we used 15 or 16 different types of HIV tests,” Munro says. “We had to ship them all in, then we had to work with diagnostic labs.”

There was no single “oh-no” moment. As the results arrived sporadically through October and November, the slow burn of concern grew.

The team kept CEPI, CSL and the Federal Government in the loop. It consulted HIV experts, including internationally renowned Professor Sharon Lewin of Melbourne’s Doherty Institute.

“To a person, every single one said, ‘Look, you wouldn’t choose [to have HIV detected], but these are just tests’,” Munro says. “There were a range of solutions.” But by early November, Pfizer was out of the blocks, with AstraZeneca hot on its heels. They had completed Phase 3 trials with good results. UQ was set to begin its Phase 3 trials, with 30,000 participants in 20 jurisdictions around the world.

The Federal Government’s scientific advisory committees, particularly the Science and Industry Technical Advisory Group (SITAG) and Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) held meetings. CSL and its partner Seqirus held meetings. The UQ team was just one cog in the wheel. They kept working.

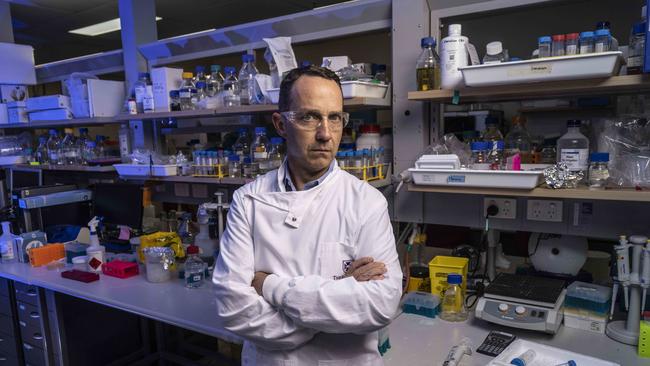

“My personal view at the time,” Munro says, “was very clear: keep going, keep going as fast as we possibly can. That decision will be made and we’ll find out but don’t slow down, don’t stop.”

In early December, the UQ team was told a decision had been made. On the night of Thursday, December 10, the key members of the UQ team logged into a Zoom meeting. The Federal Government was terminating its agreement with CSL for doses. Vaccine development was to stop. The team was devastated. But it understood.

“We all agreed in the end,” Young says. “You weigh everything and the overwhelming factor was that there looked to be a number of vaccines on the way to licensing.”

Clamp 1 vaccine is gone, never to be rolled out. CSL had to dispose of tens of thousands of doses of already made vaccine. But in our community are people who put out their arm for a jab of the homegrown vaccine in the Phase 1 trials. They are still being monitored. Their bloods are tested, their results checked. There’s no hint of HIV anymore. But the vaccine-generated antibodies for Covid-19, those disease fighters of the immune system, remain at a protective level.

“It still looks,” Young says with a hint of melancholy, “like a really solid vaccine.”

THE FUTURE

Anytime now another Esky will be jetting its way to the Netherlands, filled with scientific material from Clamp 2.0. Just what virus has replaced the HIV peptides in this revised version is not something Young is prepared to disclose until “we’re confident we’ve got something that’s working”.

That’s likely to be after the preclinical studies in hamsters in The Netherlands. Young says 20 different options were identified.

“Some didn’t work at all, some worked reasonably well and some were quite comparable, if not better,” he says. “We’ve chosen one that looks really promising. I can’t imagine it will show us anything other than the sort of results to Clamp 1 because the characteristics of the clamp are still the same.”

The fact that UQ is developing a Covid-19 vaccine is thanks in large part to CEPI’s continued backing. It had pulled its funding on the first vaccine just prior to the Federal Government’s decision to terminate its deal with CSL for the manufacture of the vaccine.

But after a review of the data from Clamp 1, “the panel was really impressed and asked us to continue with Covid-19”, Young says.

“CEPI gave us the go-ahead to commit to what they’re calling Wave 2 vaccines. The idea is that, hopefully, we will generate a Covid-19 vaccine that could be applied as a booster for ongoing maintenance of the immune protection in the community when the virus becomes endemic, if it does.”

No one in the team is setting a date for when the vaccine could be ready. The full range of clinical trials will be run, with the added complexity of dealing with a population that will have been vaccinated or exposed to the virus.

But variants are at the forefront of the team’s mind. Munro says screening of potential variants is being done now and a choice of which, if any, to target in the UQ vaccine will be made as close as possible to the time where decisions must be made on development and manufacture.

“We could make it Delta, we could make it Delta Plus,” Munro says. The consensus among the scientific community is that a diversity of vaccines will be needed.

“These protein vaccines in the future may have an important role to play,” he says. Munro says protein vaccines are tricky to develop and none of the candidates being devised globally have received approval yet. The most likely to get there first is Novavax, which released good data from large scale clinical trials in June.

That’s one of the vaccines the Federal Government punted on, with 51 million doses ordered but an Australian rollout is unlikely before next year. A big advantage of protein vaccines is they contain an adjuvant that “supercharges the immune system”, similar to the flu vaccine for older or immunocompromised people.

“We’ll see over time, if people who may have a poor immune response to AstraZeneca or Pfizer may respond better to an adjuvanted protein vaccine,” Munro says. “That might be especially important in older individuals. We don’t know that but that’s one theory and you can imagine that being true.”

Plus, mixing and matching vaccines that use different technologies may produce a more powerful response. Perhaps an mRNA vaccine such as Pfizer followed by a protein vaccine. Whatever research on that concludes, it is widely held that we will need to be vaccinated regularly – maybe every year, or five.

If all goes well for Clamp 2.0, Phase 1 clinical trials will begin in the first half of next year. The hope is that CSL will commit to producing the vaccine if it proves effective.

Another hope is that the Federal Government will dramatically increase its funding of scientific research and development.

The push is on to create the Australian Vaccine Response Alliance, an organisation made up of 40 leading scientists from UQ, the University of Sydney and the University of Melbourne to advance Australia’s capability to develop and make its own vaccines. The group would also collaborate on research into another global dilemma: the rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

At Christmas, a submission was put to the Federal Government seeking $240m over 10 years to fund AVRA with a bid to build an “idea to drug” pipeline within Australia. So far, there’s been no response.

Says Munro: “We have to think of scientific research more like how we fund the military. This is an essential service, it’s not just boffins working away in a lab because they like it. This is our survival, really.”

Young says AVRA would help translate Australia’s globally recognised expertise in discovery science in infectious diseases and immunology into the creation of vaccines and drugs.

He says Australia’s scientific community had come together in an unprecedented way during this pandemic, sharing data and expertise, and now is the time to harness that collaboration.

“During a pandemic, when things are locked down, having our own capacity to do these things would be of benefit,” he says.

“To have that capacity would allow us to build the biomedical industry and start generating vaccines of our own.” Dashes to The Netherlands might no longer be necessary.

The Federal Government has, after persistent lobbying, called for fully costed proposals to create a facility to manufacture mRNA vaccines in Australia. And in April, it contributed to a $2.2m investment in the BASE facility at UQ, aimed at lab-based research into mRNA and its role in developing vaccines and cancer therapies.

“It’s great there is an intent for investment in mRNA,” Young says, “but it isn’t the golden goose. It isn’t applicable to everything. It works very well for coronaviruses but it may not for other bacteria or viruses.”

And who knows what, or when, the next pandemic will be? It could be in two years, could be in 20 or more, but there will be a new pathogen that sweeps through populations, causing fear and heartbreak. Experts had been warning governments for decades about the inevitability of something like Covid-19. Will Australia be better prepared next time?