Chance or fate: The truth behind coincidences

They’re the freaky moments some people put down to chance, while others consider them fate. Now the experts reveal the truth.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SOMETIMES, the best story in a book isn’t the one the author intended. It’s the long-forgotten love letter found tucked between the pages, an old boarding pass that reveals your holiday read is better travelled than you, or a scribbled note furiously correcting grammar or a gaping plot hole.

Why Australian poet Rupert McCall changed his name

Brisbane man gets 3D-printed skull implant after horrific accident

That’s the magic of preloved books – the signs of life that mark their travels through lives and across countries.

It’s one of the reasons Alea Cadzow fell in love with the art of dealing in books.

“There’s just something about books on a shelf that have been somewhere and are going somewhere,” she says. They trail invisible threads, and one of Cadzow’s joys is using these strands to connect people.

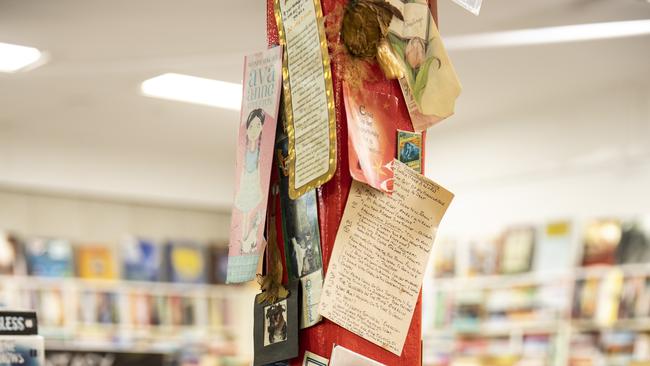

It’s the reason the walls at the Bribie Island Book Exchange – which she runs with her husband Andrew – are peppered with an array of flotsam and jetsam retrieved from books that have arrived at her door: Letters, postcards, photographs, ticket stubs and bookmarks.

They’re the sorts of things most people would just throw away but the collection of other people’s memories has become a source of delight and surprise to Cadzow and her customers.

Occasionally, a lost object will even find its way back to its owner.

“Love letters are the big one,” Cadzow laughs. “People think they’ve put them somewhere very secret. No one will find it because it’s in their own book, right? Then forget all about it and they end up here.”

She loves nosing through newly arrived books and has come to expect almost anything, like the perfectly pressed marijuana leaf between the pages of a Bob Dylan biography.

But all previous finds paled into insignificance the morning she opened a book and found a note from her own long-dead grandfather. In an incredible coincidence, a book lost almost three decades earlier and more than 1000km away had found its way to her bookshop on the waterfront at Bribie Island, north of Brisbane.

The thread of this unlikely coincidence tracks back to Sydney in 1986, when Alea’s grandfather rather optimistically gifted her a copy of the classic reference on Greek and Roman antiquity and fables and myths, Bulfinch’s Mythology, for her 12th birthday.

“He had very, very high ambitions for me in the world of literature, which was never going to happen,” she laughs, explaining she hated reading as a youngster.

For the next few years her grandfather would ask almost weekly about the book and she would dodge his questions and come to one firm conclusion: “The worst thing you can ever do is buy someone a book and tell them they have to read it.”

In 1990, the family moved and – call it divine intervention – Bulfinch’s Mythology was in a carton of books that went astray somewhere between Sydney and the opal mining town of Lightning Ridge in outback NSW.

At the time, she was grateful to be rid of both the book and the responsibility of reading it. But as the decades passed and her grandfather died, she felt a nagging sense of obligation. “I always kind of felt like I should end up reading Bulfinch’s Mythology.”

In 2018, she thought the universe was giving her a poke when a copy of the old classic turned up at the book exchange, but it was falling apart, with dozens of pages missing. “It didn’t matter how much you wanted to read it; you couldn’t,” she remembers. “I threw it out into the universe and said OK – I want a better copy.”

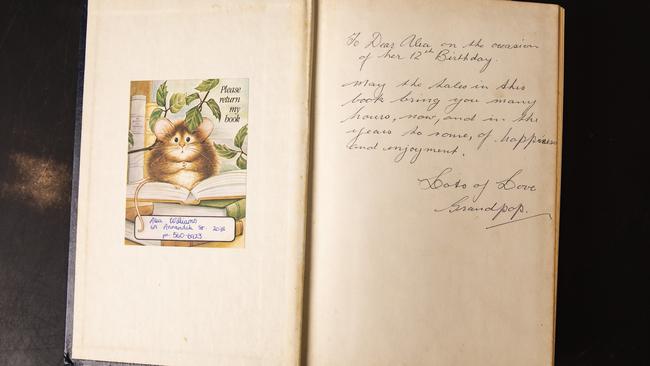

About a month later, as if on cue, another copy turned up at the shop. That seemed coincidence enough … until she opened the front cover and saw a familiar inscription: To Dear Alea, on the occasion of her 12th birthday. May the tales in this book bring you many hours, now, and in the years to come, of happiness and enjoyment. Lots of Love Grandpop.

Opposite, in her own tweenage script was her name, as it was then, Alea Williams, and her address. The book her grandfather had given her 32 years ago in Sydney was in front of her … in near perfect condition. Dumbfounded, she wandered out to the footpath and looked up and down the street. Nothing.

The book had been in a bag dropped off earlier that day by a woman who said her friend had terminal cancer and was clearing house. But she had never seen the woman before nor since. Despite every effort, Cadzow has been unable to trace the owner, or make sense of how a book lost in NSW decades ago could have found its way back to her.

“So how did it get here? We don’t know.”

Although she’s a “math and science person” she says it’s hard not to feel the coincidence carries some significance. “I felt like I was being disciplined from the grave, but also that he [her grandfather] was having a laugh.”

The links in the chain that brought this startling coincidence together have Cadzow in awe. She was not supposed to be working that day and had another staff member sorted it, the book would have likely just gone on a shelf and been sold. Even the fact she ended up owning a bookshop in the first place is remote, and due almost entirely to her book-mad husband.

“I don’t even know what to say. The chances of this happening are so small.”

Chance, statisticians tell us, is something human beings are absolutely terrible at calculating. It’s why casinos make so much money and we are endlessly fascinated by coincidences.

We tend to underestimate high probability events and over-estimate the low ones.

So, events we find surprising can be more likely than we think. Take the birthday paradox. It demonstrates than in a class of 23 students, there is a 50-50 chance two students will share the same birthday. Bump that number up to 75 and the odds soar over 99 per cent.

Conversely, mathematicians explain that highly unlikely events actually happen quite often due to the Law of Truly Large Numbers, which states that with a large enough sample size “any outrageous thing is likely to happen”.

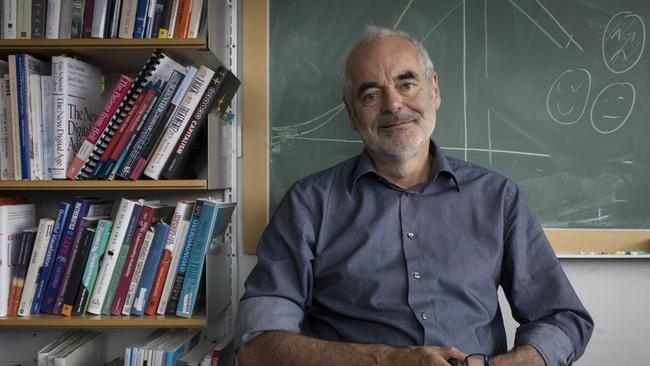

Professor Sir David Spiegelhalter is perfectly positioned to be just such a coincidence party pooper. He was knighted in 2014 for services to statistics (try saying that three times quickly), and is currently the Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk, a position created by the UK’s Cambridge University to help the rest of us make sense of statistics.

You would expect him to be nonplussed by coincidence stories, but he adores them.

He’s so intrigued, that in 2011 he founded the Cambridge Coincidences Collection, an online repository that gathers, categorises and rates coincidence stories from around the world.

Speaking from London, where he has been heavily involved in commentary and analysis of COVID-19 data, Spiegelhalter is keen to take time out to talk about something other than coronavirus. In fact, seeking an escape from the heaviness of his primary research area – risk analysis – originally gave rise to his delight in coincidences.

“Everything I do is to do with death and disaster – rare negative events,” he says. “But coincidences? I love them because they’re what I call the upside of risk. They’re the rare things that happen to us that are not getting run over. I revel in that.”

The Coincidences Collection gave him an opportunity to not only gather some great anecdotes, but to look for common themes.

“What’s interesting to me is what people notice and what they consider remarkable in coincidences.”

Spiegelhalter says most stories hinge on finding unexpected links to a stranger, object or place. “It’s all to do with completing circles of connection,” he explains.

“Essentially, we have this enormous need to find structure because we find it quite difficult to believe that so much that happens around us is completely random and chaotic.”

But it is, he contends.

“I don’t believe there’s anything meaningful going on, but that doesn’t stop me really enjoying a juicy coincidence. I just believe the sheer number of possible connections we all have – there’s bound to be some remarkable coincidences that happen all the time.”

Spiegelhalter uses a scale of “once in a lifetime”, or “once in 100 lifetimes” to attach probability to complex coincidences in a meaningful way. So, a “once in a lifetime” story would be ironically rather run-of-the-mill because, by definition, everyone would have one.

A really impressive story would be the kind of thing only one in 1000, or so, people have experienced.

Despite hearing many incredible stories of chance, Spiegelhalter says the truly surprising thing about coincidences is not that they happen, but that they don’t happen more often.

“The coincidences we hear about are only the tip of the iceberg,” he says.

Below the waterline are the vast number of coincidences that never quite happened – the near misses. They’re the connections that exist but people didn’t discover, because they didn’t talk to a stranger or open a book.

The self-deprecating statistician reckons he’s likely missed a few.

“I’m a miserable Englishman who never talks to anybody on public transport, so I could have been sitting next to my long-lost twin brother who I was separated from at birth and I’d never have known because I just got up and walked away at the end of the journey,” he jokes.

While Spiegelhalter uses the hypothetical situation to make a point, Toowoomba’s Terry Gall has found himself in an eerily similar situation, unknowingly crossing paths with not one, but two long-lost brothers.

The strange story begins in Sydney in the 1960s when Terry’s mother died and he and his older brother Barry were separated, adopted by different families. (They didn’t know, but there was a third brother, David, whom their mother had adopted out at birth and never told them about.)

Throughout his life, Terry searched Australia coast to coast for Barry with no luck and no help from authorities. They would only tell him his brother had “gone west” from the Sydney orphanage – not much help, given most of the country is west from there.

In 2018, more than 50 years after the brothers were separated, Terry’s adult son managed to track Barry Sutherland down through an online genealogy site.

This is where the story takes an uncanny twist. When the brothers met in Toowoomba for the first time, they were bonding over the fact Barry lives in Dubbo and Terry had recently passed through the regional NSW city on a driving holiday.

They were looking through Terry’s holiday snaps when Barry stopped, stunned. He was staring at a photo of a whimsical metalwork sculpture of an emu riding a bicycle.

Terry explained the huge artwork in the front yard of a house in Dubbo had caught his eye, so he’d stopped to take a picture.

“That’s my house,” Barry said. He’d welded the emu himself. The revelation gave Terry chills. A year before they found each other, the brothers had come tantalisingly close to meeting when Terry stopped at Barry’s front fence.

“I’ve travelled and lived in four different states and to be able to be that close and still not know he was there,” Terry marvels.

“Here we were standing outside his house.”

Late last year, the story had a sad bookend, with another incredible coincidence missed.

In September Terry found out about the third brother, David, but only after David died and relatives managed to track Terry down for the funeral.

It revealed the spooky coincidence of their parallel lives. While all brothers were born in Sydney, as adults both Terry and David ended up moving north and settling just kilometres apart in Toowoomba.

What’s more, David had been a carpenter, while for the past eight years Terry has worked at the local Bunnings hardware store.

“For years he lived under my nose – it’s hard to believe. There’s no doubt we would have crossed paths but I never knew he existed until the day before his funeral.”

When he attended the funeral, Terry found he knew many of David’s friends.

Terry Gall is in the rare position of getting a glimpse at how destiny almost, but didn’t quite, hit its mark.

When destiny does shoot true, it can evoke a profound emotional response. Glenda O’Brien opened a Facebook message in February this year and burst into tears. On her phone was a photo of a friendship ring lost on the Gold Coast 46 years earlier.

“That feeling when I saw the ring; time just sort of stood still for a few seconds,” she says.

“It was bizarre. Surreal. I really felt that ring had come back to me.”

In the real world, it was a trinket. But in O’Brien’s world the ring had a sentimental value that eclipsed its price tag. Given to her in 1971 by a smitten 16-year-old and inscribed “To Glenda, Love Phillip”, it signalled the official start of a relationship that was still going strong half a century later.

The ring had slipped from O’Brien’s finger and been lost way back in 1974 when she was washing her car on the dirt driveway of a block of flats at Mermaid Beach. Realising she had probably tramped it into the soggy ground, O’Brien searched to no avail.

The couple moved a few years later and the flats were demolished, the site remaining vacant to this day. Although the ring was gone, the wide band had left its mark – a lonely callus on her finger.

“I used to look at that callus and think about my ring,” she says.

Now, nearly half a century later, here it was large as life. Metal detectorist Jason Kemp had posted a photo of it on a Gold Coast community Facebook page after finding the distinctive ring 20cm underground on a vacant block at Mermaid Beach. The inscription caught the eye of a former colleague of O’Brien’s who remembered she was married to a Phillip. Just maybe.

Although the pair had not been in touch for more than a decade – and she had never heard the tale of the lost ring – she tracked O’Brien down online and shared the post.

The message zinged through the aether and hit O’Brien with a powerful flash at Hervey Bay, where she and Phillip now live.

“As small as it is, this really blew me away, the string of events for this to happen. It’s not just that it was found, it’s that an honest guy found it, that he put it on social media, a friend I haven’t seen for years saw it and found me.”

The friendship ring is now a symbol of so much more. Each night O’Brien places it in a box beside her bed.

“I leave it open so I can see it. It will go to my granddaughter and so will the story.

“It made me realise that you never give up on anything in life. There’s always a chance if you stay positive.”

Coincidence, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Two people hear the same anecdote. One marvels at the odds, while the other ponders the greater meaning.

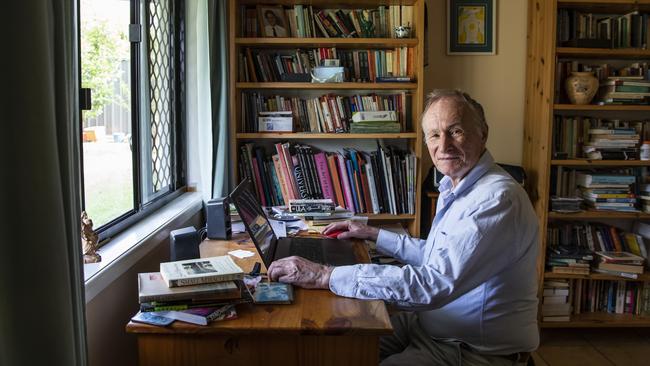

“There is this huge impasse,” explains Laurence Browne, coincidence buff and honorary research fellow in philosophy at the University of Queensland.

“There are two ways of looking at coincidences. One is that they’re just chance; and the other is that they are more.”

And never the twain shall meet – you’re either a rationalist or a believer. But Browne hopes to forge some middle ground.

He devoted his doctoral thesis Examining Coincidences: Towards an integrated approach – and later a book, The Many Faces of Coincidence – to arguing the differing perspectives need not be at loggerheads.

“I’m not anti-statistician – they’re very important. But you can’t use chance to explain everything.”

Chance is perfect, for example, to explain why in 2018 a Sydney man won the Lotto twice in one week, picking up $1 million on Monday and $1.5 million on a Saturday draw. Where it falls down, he says, is in fully accounting for coincidental events that seem richly imbued with meaning, such as Alea Cadzow’s book.

While chance may explain the probability of an event occurring, Browne says it does not explain the emotional resonance felt by those who have experienced a meaningful coincidence: the flash of insight; the sense of connectedness. Even just hearing a cracking coincidence anecdote can trigger a physical reaction – goosebumps.

Browne proposes multiple categories for classifying coincidence which would include chance, but also more controversial divisions, such as supernatural coincidence: for events where it seems a higher power or “sixth sense” is at play; and synchronicity (an idea pioneered by Carl Jung): for coincidences linked by meaning and accompanied by insight.

“I’m not arguing with chance. This is parallel to chance,” he says.

While it may seem outlandish, research in quantum physics – where entangled particles seem to act in correlation even when separated by great distances – gives Browne hope that science may lead to a different understanding of how matter is connected.

But for now, the disparate perspectives agree to disagree, albeit very civilly, with statistician David Spiegelhalter adamant only one category is needed to classify coincidences – chance.

“I like the idea of synchronicity and other ideas people have had, but I don’t believe in them at all. I don’t think there’s any underlying force or greater meaning. This is pure randomness,” Spiegelhalter says.

There is one thing on which both statistician and philosopher agree – discovering coincidences can be good for the soul, and good for society. And if you long to experience an extraordinary coincidence there’s a simple way to boost your odds – take notice of your surroundings and talk to strangers.

“So many coincidence stories come about because people talked to a stranger,” Spiegelhalter says.

“There’s only so many degrees of separation between all of us. Explore that and you’ll find some. Think of all the people you have never spoken to, and the countless connections that you miss because you didn’t notice them.”

Whether you believe in fate or chance, it’s not bad advice for life: be in the moment; talk to strangers; smell the roses and look in books.

As for Cadzow, has she finally read Bulfinch’s Mythology? “Kind of,” she says, squirming just a little, as her 12-year-old self resurfaces. Sorry Grandpop, but sometimes the story of the book trumps the story in the book. ■

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas