Acclaimed Indigenous artist Helicopter Tjungurrayi reunites with family of pilot who saved his life

In a tiny outback town surrounded by desert, an acclaimed Indigenous artist finally meets the daughter of the helicopter pilot who saved his life 65 years ago.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s 36 degrees when we arrive at the art centre, but nice and cool inside. It’s taken a long time to get here.

Helicopter Tjungurrayi is sitting in a corner, waiting for a meeting that will transport him back 65 years, to the day his life changed forever.

You’re drawn to him instantly, but the old man with the thick beard and glasses and the winter clothes, is used to it. He’s a celebrity around these parts. Even the quarantine officer who confiscated our fruit on the NT-WA border told us to say hi to Chopper.

A living link to 60,000 years of history, Helicopter was about 10 in 1957, living a nomadic existence with his people, with no knowledge or need of the modern world, when a fluke encounter with a white man saved his life and transformed the lives of everyone he knew.

The renowned Indigenous artist is waiting at the Warlayirti Art Centre in Balgo, in the remote northeast of Western Australia, to meet the daughter of the Queensland helicopter pilot who rescued him when their lives, and worlds, intersected. Two chairs are set up, with Helicopter in one, wired for sound. Lisa is ushered in. The artists and centre workers and other visitors have gathered around. They don’t want to miss this moment.

The centre director explains to Helicopter that this is the daughter of the man who flew him as a very sick child to Balgo, all those years ago.

“Your daddy?” Helicopter asks.

“My daddy,” Lisa says as the tears start to flow.

FIRST CONTACT

First came the noise across the still desert. A disconcerting chop-chop-chop that came from everywhere at once and didn’t seem to be of this world. The small group searched the land all around them, until someone looked up into the sky.

There it was, but what was it? The sun shone off its body. Its wings flashed in a circle. Olodoodi Tjungurrayi thought it was manurrkunurrku, a dragonfly. The sick young boy couldn’t think of a word for it. It was the strangest thing he’d ever seen.

Then it was gone, and the family group of about 30, living on their country at Natawalu as they had for more than 2000 generations, was left to wonder what it was.

Some had heard about the white man, and the place north of their country where many of their people had gone and not returned, but this was something else entirely.

Over the next few days, the dragonfly returned. And by watching its movements they could pinpoint where it was coming to rest at night. The bravest men decided they would investigate.

Jim Ferguson had seen a young Indigenous woman, alone, as he piloted the Bristol Sycamore over the Tanami Desert in 1957. But he had a job to do. The chopper, leased from Sir Reg Ansett, was conducting gravity surveys around Well 40 on the Canning Stock Route, a rarely used and rough track that connects the Kimberley to the centre of Western Australia.

The survey was looking for anomalies that might indicate the presence of mineral deposits in this empty corner of Western Australia.

At the crew’s camp, two worlds collided. The men, led by a warrior who would later take on the name Brandy – his job in the white man’s world was to brand cattle – approached Ferguson and his team through the spinifex and the red dust. Ferguson knew something wasn’t right.

A tough man with a thirst for adventure, Ferguson had grown up on cattle stations around Cunnamulla in western Queensland, where his mother was a camp cook. He hadn’t gone to school until he was 11, and he knew a bit about Indigenous culture. Seeing dust kicking up behind the approaching men, Ferguson drew the revolver that he always wore on his hip when out in the bush.

As Brandy’s daughter Frances tells it, Brandy sprung his trap. He was dragging a spear behind him, clasped between his toes. He flicked it up behind his back, grabbed it firmly and threw his spear.

It’s a neat trick. In 1790, an Indigenous warrior on Manly Beach in Sydney pulled the same move and pierced Governor Arthur Phillip through the shoulder.

But Brandy didn’t launch his spear at the white men. Frances says he hurled it at the helicopter, and it clattered off its aluminium skin. Ferguson fired a warning shot that reverberated across the desert.

First contact had been made.

In 2008, Ferguson told the story a bit differently, saying he had drawn his pistol, and another man grabbed his .303, but the warriors stuck their spears in the ground, indicating peaceful intentions.

Contact made but curiosity running wild, the group later approached the camp as the white men were cooking a meal. Brandy went forward and asked for a drink of water.

The white man went to his fire and prepared a billy. He brought it back and offered it to the group. What was this black, smelly, bitter water?

Brandy took a sip and spat it out. It was his first drink of coffee.

The two worlds began to tolerate each other’s presence – strange food was offered but not eaten, and a few of the desert mob even got to play with the radio, to the amusement of everyone.

The flash on the camera scared Walapayi so much he took off over a sandhill.

But the desert dwellers knew there was something they must ask these strange men who came from the sky.

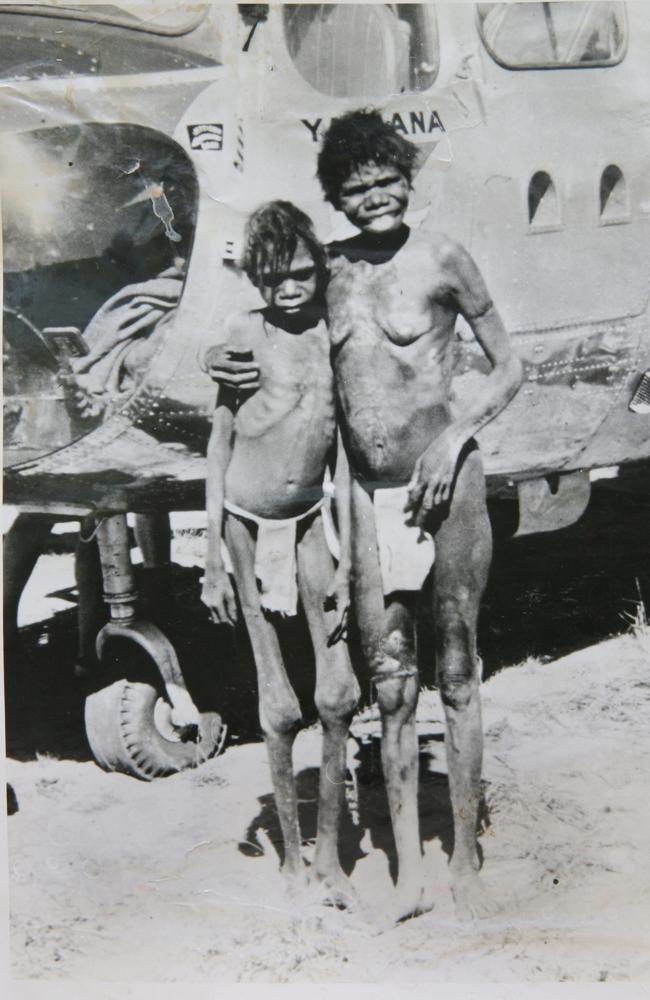

The boy, who was about 10, had always been a sickly child, but now they were worried that he would die. He was painfully thin, his knees were grotesquely swollen and he was covered in sores.

They approached the helicopter with the boy and Kupunyina – his aunty. She had a spear wound in her leg that had become infected and also needed attention.

Before he died, Helicopter’s brother Charlie Wallabi explained what happened next. “My younger brother was so sick; he had sores everywhere and he was helpless, a little boy,” Wallabi said.

“I grabbed my little brother and showed them. So kartiya (white person) looked at his sores and said, ‘OK, we will take him’, because he is so sick.

“So I ask the kartiya, ‘Are you going to bring him back?’

“He was speaking his language and I was speaking my language. I kept on saying, ‘Are you going to bring him back?’”

Ferguson took a photo of the boy and his aunty, and the group of proud warriors in front of the Sycamore.

It’s tempting to imagine the terror the little boy felt as they lifted off, and his amazement in viewing the landscape from thousands of metres in the air – the symmetry in the ridges of the sand dunes, the telltale signs of soaks, the water holes, the dots of spinifex, the colours.

Ferguson landed the chopper at Billiluna Station, maybe to get advice on where to take the sick boy, and then continued on to Balgo Hills Mission, 900km east of Broome, a stark collection of stone buildings, shacks and tents in the middle of nowhere.

Already, many families from six distinct tribal and language groups had made the mission – run by Catholic Pallottine nuns – their home, as cattle and camels degraded vital water holes and made nomadic life in the desert even more perilous. They had traded their freedom for food security and the chance to give their children a white man’s education.

Ferguson brought the chopper in to land in a cloud of red dust. He explained the situation to the nuns who were happy to take the pair in.

His last, poignant memory of the encounter is firing up the nine-cylinder Alvis radial engine of the Sycamore, and looking back to see Kupunyina sitting in a Jeep wearing a new floral dress, the sickly, naked boy next to her.

I THOUGHT HE WAS DEAD

And that, for Jim Ferguson, was how the story ended – at least for 51 years.

At some point during that job in the Tanami, he’d acquired a wirkli, or “number seven” boomerang, because of its distinctive shape. He’d found it at an abandoned campsite, and left some rifle bullets behind in exchange.

It was an act that had been repeated thousands of times on the Australian frontier. In 1777, Captain James Cook had left a specially minted medal behind after he found some native artefacts at an abandoned campsite at Bruny Island off the coast of Tasmania.

Of course, Cook’s artefacts and Ferguson’s boomerang had not been abandoned. They had been left out in the open by people who previously had not needed to worry about the security of their possessions. And the “abandoned” campsites were most likely deserted in a hurry just before the arrival of these strange white people. In 2010 Ferguson donated the boomerang to the National Museum in Canberra.

Ferguson lived an adventurous life – he’d flown fighter planes off aircraft carriers in the Korean War, and later choppers in Vietnam.

He’d had other first contact experiences, and passed them on to his children – how he’d spotted the dust at the warriors’ feet, how they’d spat out the coffee …

Then one morning in 2008 Ferguson was reading The Weekend Australian at his home in Willaura in country Victoria, and almost spat out his own coffee.

A feature story on the Canning Stock Route touched on a Balgo artist called Helicopter Tjungurrayi – so named because in 1957 a man flew him to a mission and probably saved his life.

Ferguson was stunned.

“I assumed the boy had died,” he told the same paper a month later. “I’m absolutely thrilled that after all these years, he’s still alive and I played a small part in that.”

Ferguson placed a call to the Warlayirti Art Centre in Balgo – the town had moved up the escarpment from the old mission in 1965 when the water dried up, and through an interpreter managed to chat to Helicopter.

“Thank you very much for taking me to Balgo,” Helicopter said to Ferguson.

“I’m happy now.”

Ferguson, then in failing health, declared: “It might be the last thing I do, but I’ve decided I’d like to meet him.”

WILL THEY BRING HIM BACK

After the chop-chop-chop of the Sycamore slowly faded, the desert mob were faced with a dilemma. Would the kartiya bring the boy back to them?

Charlie Wallabi said: “I waited, waited, waited for long and I wondered, ‘They’re not bringing him back!’ Nothing. It was getting a bit longer, and I said to myself, I think I’ll go after him north. From there I kept walking right, long way, all the way to Balgo.”

All of the Natawalu group – bar one who was completing his initiation – headed on the 300km trek north, eventually finding the boy, now known as Helicopter, and Kupunyina at the mission in what must have been a joyous reunion.

Most of the local groups had already come in from their country, to Balgo mission or other outposts. As more people left their traditional lands, the pool of potential brides and husbands shrank, condemning the Indigenous people of the Tanami to the same fate of those from across the country. Helicopter’s hardy group was among the last living in the traditional way.

But Helicopter was not out of the woods when Ferguson left him with the nuns.

He was taken almost 800km to Derby Hospital on the WA coast. No one really knows what he was suffering from in the desert. Ferguson thought it might be rickets. It certainly wasn’t malnutrition, as others in the group look as fit as Olympic middle-distance runners in the photos. Some of the symptoms appear similar to rickets, which can be caused by a lack of dietary vitamin D and certain genetic conditions.

Helicopter says he was often sick as a boy and suggests he had an operation on his leg in Derby, possibly to drain fluid.

What is not in doubt is that Helicopter got better. He didn’t like school and didn’t stay long. He never learned much English, although he can hold a polite conversation. But from the perspective of decades, he respects the nuns for the discipline they drilled into the children. Other senior members of the Balgo community have different opinions.

The mission educated the children but restricted the time they could spend with their families. Older family members lived in humpies on the fringes of the mission, collecting rations to supplement hunting and bush tucker. There was no going back to the old ways. Freedoms had become dependencies.

As a young man, Helicopter toiled in the quarry, cutting the flint-hard red desert stone into blocks to build the church and other buildings at the new town of Balgo. He raised a big family with beloved wife Lucy Yukenbarri, who died in 2004.

In 1987, the Warlayirti Art Centre opened in Balgo – an institution that would gradually take over from the church as the heart of the community.

Lucy was an early star, with her kinti-kinti technique of overlapped dots hugely influential among the art community. Helicopter would accompany her to the centre, to support her, tell stories, and watch her paint. Gradually he was drawn into her world.

“Balgo is known for art partnerships – men and women finishing each other’s paintings,” centre director Poppy Lever says. “Helicopter was happy to sit there and help Lucy with her works. But towards the late ’90s he started painting himself – and he flourished.”

He quickly became a sensation, with solo shows across Australia and a trip to Tokyo to paint BMW cars, of all things.

There was even an exhibition in London. Helicopter, who wears a long-sleeve shirt and a jacket in the heat of the desert, remembers the cold.

“I was going to meet the Queen,” he explains through George Lee Tjungurrayi, linguist, community leader and Helicopter’s grandson. “But she was hunting.”

If you’re going to stand up Helicopter, that’s not a bad excuse.

Helicopter walks from his humble house to the art centre every day. He’s the first to arrive and the last to leave. He’s a calming, generous, grandfatherly presence.

“He’s got a lot of family around, a lot of beautiful dogs that keep him company,” Lever says. “He’s got a brilliant, lovely life, and there is so much pride and love for Chopper here.”

I PAINT MY COUNTRY

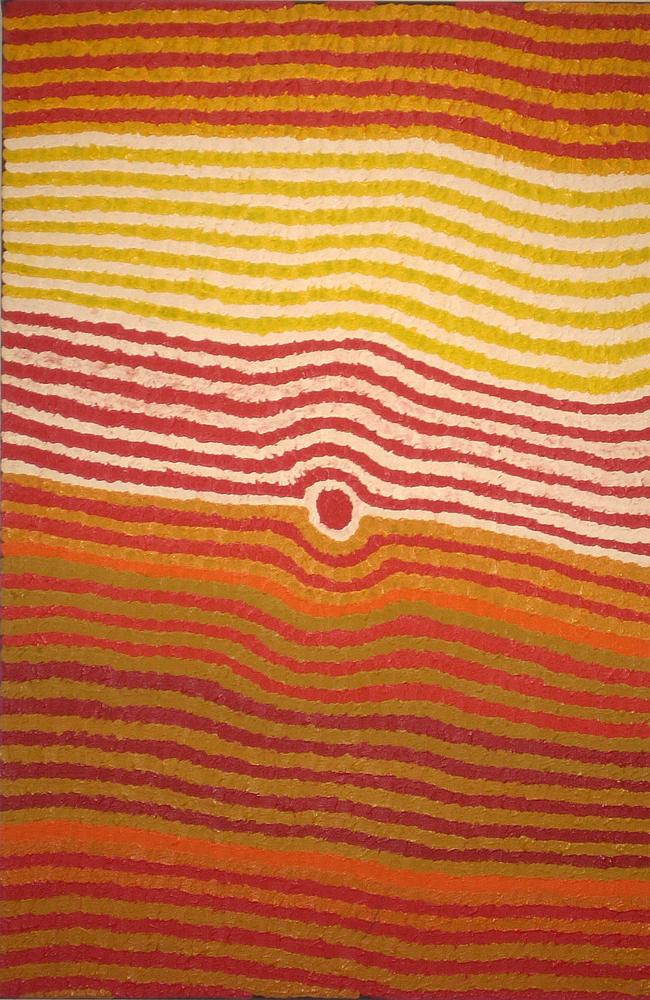

The art of Helicopter, and Balgo, is unique.

Tribes that lived in the desert had no rock art tradition like in the Kimberley, but they expressed themselves through sand stories – literally telling stories by scrawling in the sand, as well as body art and decoration for ceremonial purposes.

Iconography from these art forms was adapted to painting.

But when it comes to inspiration for the paintings, there is a re-occurring theme.

“I paint my country,” Helicopter says.

Like a view from a helicopter, he paints the ridges of sand dunes, the water holes, the soaks of a land 300km south, a country he visited again in 2000 for the first time since 1957.

John Carty, head of humanities at the South Australian Museum, literally wrote the book on Balgo. He went there in 2002 to research his PhD on Aboriginal art, stayed for years and returns regularly.

“Balgo is the sort of place that gets under your skin pretty quickly,” he says.

Carty’s magnificent book Balgo: Creating Country, explains the link between country and art. “Country is not just landscape, it’s people, relations and all of your memories,” Carty says. “To paint your country is to bring it back.”

On that visit to country in 2000, Helicopter began following the landscape, pointing out the features, and where to find water and bush tucker. All the while he was singing to himself.

Giancarlo Mazzella, a community development officer with Boab Health Services and a mate of the man he calls Chopper, explains. “The old fellas sing the country,” he says.

“It’s like a navigation tool, a map.”

Helicopter has returned to Natawalu since, although he was not up to making the last trip. Since taking over running the Warlayirti Art Centre five years ago, Lever has organised regular trips to country for the different language groups living in Balgo. Art and country are the same thing.

“It’s a big part of what we’ve been doing – keep country alive, keep culture alive and keep story alive,” Lever says.

“In some cases people had been painting their country for 20 years and they’d never been there.”

LET’S GO TO BALGO

Jim Ferguson never got to meet the fine man the sickly little boy he rescued became. There were plans for a reunion at a Melbourne exhibition, but Ferguson’s failing health put paid to that.

When he died in 2018 at the age of 89 there was talk of getting Helicopter to the Brisbane funeral, but nothing came of it.

For Perth teacher Lisa Ferguson-Bissell, her father’s death awakened the desire to meet this man, to sit down with him and share his stories. Tough and adventurous like her dad, the 60 year old felt like she had unfinished business.

“He used to tell us all these stories from meeting Aboriginal people in the desert but he never spoke about the boy he saved until it was in the paper in 2008,” she says.

For me, the chance to be part of this incredible meeting came about at a funeral, or more accurately, a wake. Engineers Gordon Anderson and my dad Jim Hilferty were partners in a helicopter company called Rotor-Work, along with pilot Jim Ferguson.

Formed a few years after Ferguson’s encounter at Well 40, the three had all worked extensively doing mineral research in the desert, and loved to share first-contact yarns during smoko at their hangar at Bankstown Airport in Sydney.

In the late sixties, they supplied the ranger helicopter for Skippy the Bush Kangaroo. Ferguson flew it, just passing as the dashing Jerry while wearing a girdle and a blond wig.

At Anderson’s wake on Sydney’s Northern Beaches early this year, Lisa and her daughter Amy invited me and my sisters Megan and Fiona to come along to meet Helicopter. We jumped at the chance.

After months of planning and a couple of days driving the 1200km from Darwin we met Lisa and Amy in Halls Creek, 260km north of Balgo. They had flown from Perth to Kununurra and picked up a hire car from there.

It’s fair to say Halls Creek doesn’t have a great reputation. Youth crime is rife. The car hire places advise you not to stop there. The Kimberley Hotel is behind razor wire and patrons are breathalysed before they can enter the bar.

But we were all excited when we met up in the beer garden, only to hear from other patrons that the Tanami Road, the only way into Balgo, was closed after recent and unseasonal heavy rain. Hearts sank.

The next morning, boosted by rumours the road might be open, we headed down the Great Northern Highway to the Tanami Road turn-off, with every eye straining for the road conditions sign.

TANAMI ROAD: OPEN.

LIFE IN BALGO

The Warlayirti Art Centre at Balgo welcomes travellers, but it’s not a tourist attraction. It exists to benefit the artists, provides materials and a welcoming space. It markets their works and splits the profits. But it has become so much more to a town that is very much out of sight, out of mind.

Successful artists help support extended families. About 350 people live in Balgo and most rely on Social Security payments. Prices at the community store are steep as everything has to be trucked in along a road that can close at any time.

Many locals supplement their diet by hunting kangaroos, goannas, feral cats (known ubiquitously as pussycat), foxes and rabbits. Bush tomatoes, onions and potatoes are highly valued.

Change may be coming to Balgo. There are plans to pave the 1000km Tanami Road all the way from Halls Creek to Alice Springs. It will increase safety, job opportunities and reduce the price of goods at the community store. But it will also bring tourists, and Lever fears the art centre, and the town, isn’t ready.

“If they are not prepared, communities will collapse,” she says. Lever is critical of governments who “throw money, but don’t invest” in Aboriginal communities.

“We need really targeted, thoughtful investment – it’s obvious stuff if you listen to the communities.

“The girls love doing hair and makeup, the men are incredible bush mechanics, why don’t we have trade schools?”

But she warns against “white fella aspirations” clouding the view of the town.

“People are really content in this place – they love Balgo,” she says. “We’ve got a very different way of looking at what a comfortable life is – you don’t need that much to be comfortable and content.”

YOU JUST COULDN’T MAKE IT UP

At their first meeting, after the tears have subsided, Helicopter – now about 75 – starts telling his story to Lisa. He’s so expressive that even when you can’t understand what he’s saying, you think you can. “He bring me from Natawalu to here, Balgo, when I was a little boy,” Helicopter says.

Lisa tells him she had recently been on a European holiday and had seen one of his paintings in Paris. She asks if she can show the photos her father took back in 1957. Helicopter starts naming his relatives.

“This one, my brother, this one my brother-in-law.”

He explains what life was like before. Although he was often sick he remembers playing and learning to hunt kangaroo, goanna, rabbit, fox, pussycat.

They weren’t yet familiar with the kartiya, but they knew his feral animals.

At the art centre they’ve heard Helicopter’s story many times but everyone is transfixed. It’s an incredible yarn. John Carty, who knows the tale better than anyone, is still awe-struck.

In his early years in Balgo he became fascinated with the yarn of how Helicopter’s mob – which included many people who would go on to become influential artists – came in from the desert.

He corresponded with Jim Ferguson and spoke to many other key characters – including Charlie Wallabi, before they passed. He generously allowed me to use his work to help tell the incredible yarn that has become desert lore but deserves to be known across the nation.

“A story of a kid getting rescued from the middle of nowhere, and going on to become a famous artist?” Carty says. “It’s crazy – you just couldn’t make it up.”

Frances, whose father Brandy is in the photos and was a key figure in the desert drama, steps forward as they start scrawling names on the copied picture. Later on the sidelines, she starts telling me her favourite story from her father’s first contact with the white man.

As Carty would later tell me, for the desert mob it’s the funniest joke in the world. “My father asked them if they had any kapi,” she says. “Yeah, coffee,” I reply. I’ve heard this story before.

“No, kapi,” she corrects me. “Kapi is water.” Frances Nowee, Geraldine Nowee and Jane Gimme – all respected Balgo artists – crack up.

It all makes sense – a single moment, passed down through oral histories since 1957. From Jim Ferguson to his workmates during smoko at the hangar. From Helicopter and Brandy and Charlie Wallabi to their kids and extended families and friends around the campfire.

And all this time the white fellas were missing the joke.

I DIDN’T WANT TO MISS ANYTHING

Later, Lisa is still wiping away tears as she reflects on the meeting. Helicopter also admitted he was fighting back tears.

“After all these years of thinking about it, it was very emotional,” she says. “I was so surprised he was so interested in me, and I felt like I knew him.

“The stories that my father told me, like the coffee story, it actually did happen, it wasn’t just a fairytale.”

She’s proud that her dad took the time to get to know the people from the desert, and cared enough to fly Helicopter and Kupunyina to Balgo. “He could be such a gruff old thing, but on the other hand he could be a very kind person.”

The next day Lisa and Amy return to the art centre, to buy a Helicopter painting and to spend some quiet time with the man who somehow feels like family. Who knows if they will ever return to Balgo again.

“I didn’t want to miss anything, those last moments with him,” Lisa says.

THE MAGIC LIGHT

After the meeting in the art centre, we ask Helicopter if we can take him to the ruins of the old mission for some photos. George Lee Tjungurrayi goes with us.

After some amateur off-roading, expertly guided by George, we arrive at the forlorn timber frames and stone piles, almost glowing in the late afternoon light and thick with memories. As I help Helicopter out of the four-wheel drive he grabs my hand and he is off, pointing, explaining. “That was the girls’ dormitory,” he says through George.

“That was where the helicopter landed.”

But the magic light is running out. And Helicopter handles the photo shoot like a pro. Later, we’re driving up the escarpment back into Balgo with the last smudge of red on the western edge of this impossibly beautiful tableau.

Helicopter Tjungurrayi chats away from the back seat in Pintupi, his language, while George, sitting upfront next to me, translates. We’re all reflecting on a great day. Then Helicopter says something that makes George pause. “Yapunta.”

“Wow,” George says. He speaks seven languages but George struggles to convey the meaning of a word with no equivalent in English.

“He says him and Lisa are yapunta.

“It’s a term of great respect.

“Helicopter has lost both his parents and Lisa has lost both her parents, and now they are family.”