A computer chose my baby: How AI created little Charlotte

Little Sunshine Coast baby Charlotte was just a tiny cluster of cells less than 0.1mm in diameter sitting in an incubator. But breakthrough IVF technology using artificial intelligence turned her into a baby. Her creation was part of an Australian-first trial. Here’s how Charlotte was born with the help of a computer.

She’s just a tiny cluster of cells sitting in an incubator.

At less than 0.1mm in diameter, or half the width of a human hair, she’s barely visible to the naked eye but sure enough, that’s her.

It’s baby Charlotte Cecilia Keys in the first hours of her life.

Cutting-edge technology has captured remarkable images of Charlotte as an embryo but what’s even more extraordinary is how this technology helped bring her to life.

Charlotte, now nine weeks old, is one of the first babies in Australia to be born with the help of artificial intelligence.

Of all the things her parents, Sarah-Eve Dumais Pelletier, 32, and Tim Keys, 33, thought would improve their chances of having a child of their own, a computer was not one of them.

Yet, here their daughter is after they endured a painful 12 months of fertility struggles, two miscarriages and a failed round of IVF.

‘She was so cute’: Dolly’s idyllic childhood before ‘nightmare’

‘Stop being busy, talk to your kids’: Dolly’s family warn parents

The husband and wife, who live on the Sunshine Coast, are among 1000 patients taking part in an Australian-first trial using artificial intelligence in the embryo selection process during an IVF cycle.

The trial, led by assisted reproductive services company Virtus Health and Swedish company Vitrolife, is underway across Virtus Health fertility clinics in Australia (including Brisbane's Queensland Fertility Group), Ireland and Denmark. The AI-software assesses hundreds of images of embryos (fertilised eggs) taken by a time-lapse camera inside an incubator over the five days they’re left to grow before selection for implantation.

Within seconds, it ranks and identifies the embryo with the highest chance of resulting in a successful pregnancy. It’s a delicate task normally done by a human.

But doctors are harnessing the power of AI to help them make more accurate decisions and, ultimately, reduce the significant emotional and financial burden IVF can have on patients. And, according to early research findings, it’s outperforming doctors.

“What we are seeing, and from our pilot study we published (in the Journal of Human Reproduction), more often than not the computer makes the right decision over the human,” says Professor David Gardner, the group director of ART (Assisted Reproductive Techniques), scientific innovation and research at Virtus Health. “The prospective trial is designed to test that, whether AI is as good, if not better, than a trained embryologist, which is a really exciting thing. It is incredible.”

Australian fertility experts believe the AI software has the potential to change the world of IVF and play a significant role in helping people like Sarah and Tim live out their dreams of becoming parents.

At their home in Mooloolaba, Sarah wraps her arms a little tighter around Charlotte as Tim sits beside her. The couple, both paediatric dentists, smile down at Charlotte and let the gravity of their journey sink in.

The joyous highs, heartbreaking lows and the hope they never let fade.

“We are so lucky, she is everything,” smiles Sarah. Tim adds, “Having a child is the one thing we wanted in life. It would have been really hard if we couldn’t ever have a child for ourselves.”

Charlotte, born on July 28, 2020, has travelled an unusual path to be here. Under different circumstances, it must be said, she might not have ever existed.

We may never quite know what got her here, but what is sure is that Charlotte is a reflection of the power of technology.

“You can see why it works because computers can detect things a human eye can’t and I’d like to think it’s helped us,” Sarah says.

“We will be forever grateful that we got offered this opportunity because now we have this healthy baby and who knows if she would be here without it.” Since the pair met in 2016 and married two years later, starting a family has been non-negotiable.

Early on, the couple felt as if infertility was everywhere as they watched friends struggle to conceive. As they shared the disappointments, it motivated Sarah and Tim to take steps to ensure they could have a baby for their own.

The pair began their IVF journey in 2018 with the thought they would freeze embryos to use down the track. It was a safeguard option. They were shocked when this plan became the start of their own infertility struggle.

Sarah found out her anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) level was low, which meant she had a poor egg reserve, and Tim’s sperm count was inconsistent.

Their chances of naturally having a baby weren’t zero, says the couple’s fertility specialist Dr Scott Salisbury, from Queensland Fertility Group, but extremely limited.

“They had fairly poor quality embryos produced from fairly low fertilisation rate and that’s a little unusual in someone youthful, which Sarah was at the time, so it was a bit out of the box,” he says.

“We look at the age of ladies all the time and her results were certainly below par.”

While the couple may use their initial embryos later, last year they fell pregnant naturally but just as their hopes were rising, they were stripped away. They lost the baby at 10 weeks. The nightmare continued months later when they endured another miscarriage at six weeks.

“It was horrible,” says Sarah, still visibly impacted by the grief.

“It was very, very, sad, you get so excited and start thinking about the baby, planning and looking at names and all of a sudden it gets shattered.”

It was made worse when, in between the miscarriages, they tried a round of IVF only to be told there were no viable eggs.

“Every day you get bad news,” Sarah says.

“You think it’s going to be easier than it is and when you realise how hard it is, it is very disheartening.”

It felt like two steps forward and three steps back. Each knock-back raised the stakes and deepened their desperation.

Sarah and Tim knew that in the scheme of IVF journeys, theirs was relatively short but Tim questioned how long they could suffer the emotional toll. It was time, they thought, to consider adoption.

“Sarah said we need to start putting in adoption paperwork because we wanted kids and it can take several years to adopt a child … we will put the adoption paperwork in while we keep doing IVF,” says Tim.

But just before they did, on their third IVF cycle, luck and technology were on their side.

“Scott (Dr Salisbury) said there was this new technology available that picks the embryo by an algorithm,” explains Tim.

“I thought, ‘Shit, yeah, whatever works’ … if we have this AI technology and that helps put more control and that leads to success, it’s pretty good isn’t it?”

The process to have Charlotte is not lost on Sarah, who is still mind-blown how Charlotte’s embryo was chosen.

“My two natural pregnancies miscarried, so in my case, the AI does better than nature.”

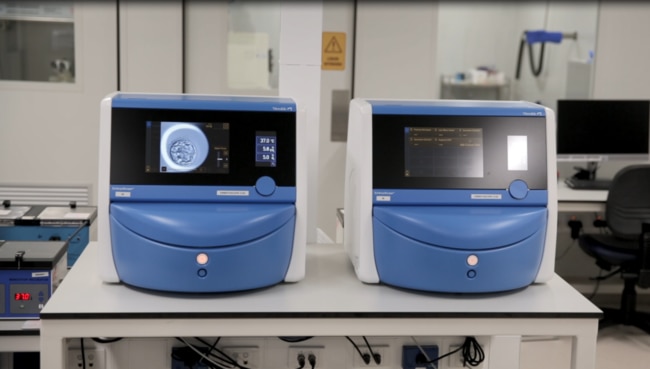

A blue, small boxlike machine sits on the bench in the lab of the fertility clinic.

The incubator, known as The EmbryoScope (manufactured by Vitrolife), is where the fertilised eggs, or embryos, are placed during the IVF process and left to grow for about five days.

Inside, a non-invasive time-lapse camera takes a picture of each embryo every seven to 10 minutes over those five days.

By the end of the incubation period, each embryo has more than 700 images taken of its development.

“Enter artificial intelligence,” beams Gardner, as he explains the intricacies of the AI. “This is a potential game-changer.”

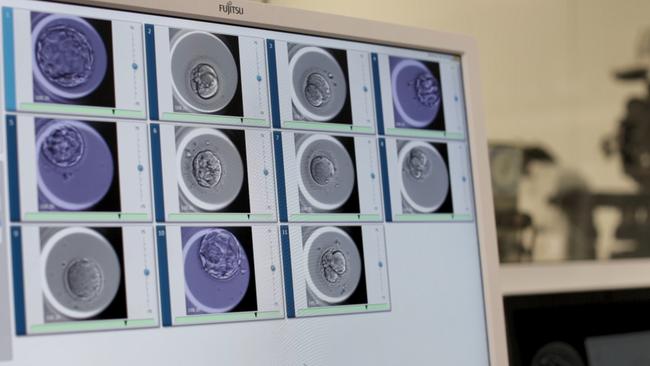

The enormous amount of data is fed into the AI-program, which then analyses every image and selects the embryo with the highest chance of resulting in a successful pregnancy.

Gardner says what would take a scientist 30 minutes to do, the computer does in 30 seconds.

“What it does is rank them (embryos) in order of which embryos will give us babies,” he says.

“It’s taking information from every image, analysing every pixel from every image and doing that 700 times for every embryo.”

Unbelievably, the AI taught itself how to select the best embryo.

In the training phase, 10 million images of embryos of varying qualities were analysed by the computer over five days, Gardner explains.

It was only told which embryos resulted in a pregnancy and which did not and, from there, it developed a system to identify high and low quality embryos.

“I’ve been doing this 35 years plus and I can guarantee I have not seen 10 million images, it went through 10 million images in five days, isn’t that incredible?” Gardner says.

Traditionally, doctors would open the incubator every day to check the progress of the embryos manually.

Many use the grading system Gardner developed to assess embryos, known as the Gardner Grading System, which has been used by doctors worldwide for more than two decades.

“We are only looking at three things: the size of the embryo, the development of the inner cell mass and the development of the trophectoderm cells,” Gardner says.

“But the computer is looking at more information, it’s able to compute so much more.”

The technology is still in a trial phase with results set to be released sometime next year.

So, for now, the AI is assisting embryologists, who still have the final say, but Gardner is excited by its potential.

“In the pilot study, the computer did better than me (at picking the best embryos) 10 per cent of the time,” he says.

“It just has the capacity to see things our eyes or mind can’t process.

“Things within cells, really subtle things that we don’t truly know what it sees.

“If the trial goes well then AI would become the norm, absolutely.”

Gardner doesn’t believe the AI will replace embryologists but merely play a vital role in the future of fertility medicine. “One of the things about any grading system that involves a human is subjectivity,” Gardner says.

“One embryo one embryologist determines as good, another might not.

“But the computer doesn’t care, the computer will always pick the same embryo and so what that means is we can move to automation, we don’t need the subjectivity of the scientist, the computer will say, ‘Hey, I know you three disagree on what embryo to put back but I’m telling you it’s this one.’

“That is a really good tool to help us select embryos for transfer.”

It’s Australia’s largest randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the technology and Virtus Health was the first to introduce the AI embryo selection software into its Australian clinics last year after the prototype system was developed in conjunction with an Australian technology company, Harrison-AI, that specialises in AI healthcare.

With each passing month, Gardner believes the technology is only getting stronger as it’s used on more patients and gathers more information.

“People shouldn’t be worried, it’s a tool to help us make better decisions and that’s all it is,” Gardner says.

“It will help doctors make better diagnoses and it will help those in IVF get pregnant quicker. It’s not absolute but it’s there for us to help make better decisions, it’s a guide.”

Doctors are leaving all definitive calls on the success and accuracy of the AI until the results are revealed next year but what they do know is it could be a breakthrough in IVF medicine.

“What’s impressive, sometimes you’ll have embryos and you will have three or four that all look the same and you would give them all the same Gardner Grade but the computer can differentiate the four embryos,” Gardner says.

“That’s the clever thing and that’s where it really gets powerful.

“It’s independent of the eyes, the computer sees things we don’t.

“It gets rid of subjectivity.”

It’s fertility technology at its finest and, to put it into perspective, Dr Salisbury has proved its significant power.

“I had a lady that hated me because I did something like 12 embryo transfers on her and she didn’t fall pregnant until the 13th embryo transfer,” he says.

“The AI wasn’t available then but the scientists all knew her because she had been in so many times.

“They retrospectively looked with the AI at her embryos, because the images captured in the EmbryoScope are kept for as long as we need them.

“The AI didn’t rate any of the first 12 embryos I gave her, the only embryo it rated was the 13th.

“Things like that are exciting if we can stop all that hardship and financial trouble they (patients) get along the way by honing in more quickly on one embryo, there’s a lot to be said for it.”

It also could be the reason Charlotte was born as Dr Salisbury explains how Sarah and Tim’s baby was chosen out of three embryos.

“It was still a bit of eeny, meeny, miny, moe in which one you pick and the AI made the difference, if you like, in their particular case,” he says. “Two looked similar and the third wasn’t so bad either but yes, the selection was made on the basis of the AI a little bit.”

Sarah and Tim aren’t ones for “what ifs”. They would have given up everything they had to have a child of their own.

So whatever got them there, they’re just grateful it gave them the most precious gift of all. “She is the person we love most in the world,” Sarah smiles.

“I can’t believe she is here and we get to hold her and love her so much, it’s all worth it in the end.”

Tim adds, “I think it was quite early (in the trial) for us, they couldn’t say how much the AI helped us.

“Perhaps in three or four years our data will help this technology succeed and it will be proven to succeed and therefore other couples will benefit as well.”

That’s exactly what doctors hope will happen, so desperate parents worn down by the emotional toll of infertility can see light among the darkness. So they know, when they thought it was almost gone, that there is hope.

Now there’s another helping hand, albeit a technological one, trying to make their dreams come true and, ultimately help babies such as Charlotte come into the world.